What if a pop song had penetrated the Iron Curtain or the Cold War had been fought on turntables and in car radios in Eastern Europe, in jazz clubs in the ports of West Africa? Of course, that sounds like a conspiracy myth: as does the claim that the Central Intelligence Agency, or CIA for short, used jazz in an attempt to prevent the spread of Communism. Or that the United States commissioned songs to propagate the liberal values of capitalism.

However, it is certainly no conspiracy theory that the American foreign intelligence service used art to establish what is known as “soft power”. In other words, the superiority of the West is not demonstrated by tanks but, say, by magazines (“Black Orpheus”, “Transition”), which around 1960 provided a platform for modern literature in those nations in West Africa that had just gained independence from the former colonial powers. It is not air shows and fighter jets that are a symbol of dominance, but rather exhibitions featuring works of Abstract Expressionism in the metropolises of Europe, which are presented as the antithesis of the heavily ideological Socialist Realism.

Abstract painting as an ideological vehicle?

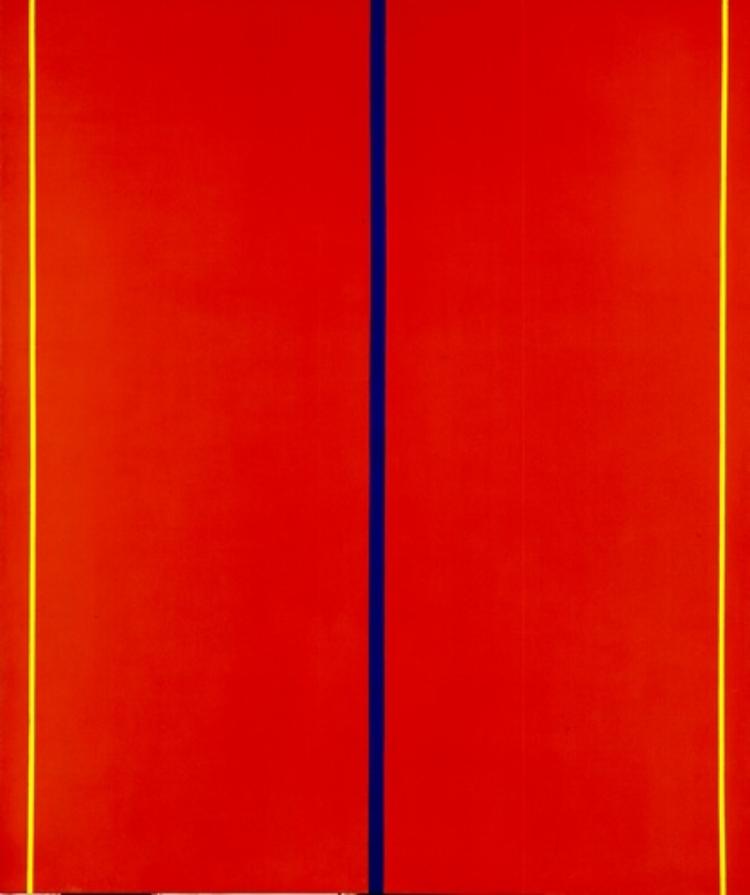

It is just that often such actions had to be kept secret – from the participating artists, too. And it can be presumed that they would not necessarily have been happy about their art being instrumentalized in this way. Let us take as an example Barnett Newman, the artist whose paintings are not only about the emancipation of the subject and pictoral space but also a declaration of independence when it comes to color. We can only speculate why the art experts of the CIA, who maintained loose connections with the Museum of Modern Art in New York, believed that radical abstract art would make a suitable ideological vehicle. However, the Abstract Expressionist artists would probably not have agreed to their work being used to illustrate the American version of liberty.

Barnett Newman, Who's Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue II, 1967 © Barnett Newman Foundation/ VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2017, Image via staatsgalerie.de/

Which is why from the early 1950s the CIA promoted what was called a “long leash policy”. In practice this meant exhibitions were funded indirectly via various channels or via non-profit organizations. In other words, financing could not be traced back to either the secret service or the American government. What was visible to the public were the names of patrons, who support traveling exhibitions in Europe.

The organization that united these various covert channels was called Congress for Cultural Freedom, short CCF. Its development is worthy of a story of its own. Suffice it to say that it originated in the former West Berlin and its roots extend back to Paris in 1949. If we believe the official version, which the CIA presents in its historiography – the CCF brought together – initially without any influence on the part of the Western powers – leftist, but also anti-Communist intellectuals and artists who feared a Communist takeover in Europe because they believed that Stalinism was detrimental to the free development of culture.

Congress for Cultural Freedom, Berlin conference, June 1960. Credit: Wikimedia Commons, Image via thewire.in

According to the official version it was only then that the contact to the CIA was established, who readily provided money for the activities of the CCF. And when the connection became known in 1966 it triggered a minor scandal. From 1950 all the actions of the CCF were orchestrated by the International Organizations Division, which was a division of the CIA and was headed by Thomas Braden. Before that he was General Director of the New York Museum of Modern Art. Apart from the idea of using modern art as a means of advertising, before long the Americans also employed music, it being an art form that would presumably reach more people. When two years after its foundation the CCF organized a performance of Igor Stravinsky’s “Le sacre du printemps” with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in Paris, it was recognized that this event was probably more moving for most people than any speech by President Eisenhower.

The CIA as a mysterious patron

Then came jazz. As was the case with abstract painting once again it was about the liberty of artistic forms of expression, especially as improvisation is an important element of it, and not conforming central to the attitude of jazz-fans and musicians alike. Arguably, the reason for the CIA acting like some mysterious patron and distributing money in this area of the arts as well was that it could claim that such music and the coolness associated with it were only conceivable in the liberal West.

With his thick horn-rimmed glasses, beard (known as the soul patch) and elegant suits Dizzy Gillespie, trumpeter and the man who helped create several jazz subgenres, embodied the new coolness. In 1956, Gillespie’s friend, Black Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., persuaded him to become the first “Jazz Ambassador” of the United States. When he was asked to attend a pre-tour meeting that would take him to Pakistan, Syria, the Middle East, Turkey and Greece he responded: “I’ve had three hundred years of briefing. I know what they’ve done to us. … I wasn’t going over there to apologize for the racist policies of America.”

His colleague Louis Armstrong cancelled his concerts to the Soviet Union one year later because President Eisenhower refused to guarantee the safety of Black students in Little Rock, in the country’s South; and it was not until Eisenhower sent in troops to protect the high schools from a racist mob that Armstrong gave concerts again. In 1961, singer Nina Simone was left in the dark about who had sponsored her concert in Lagos. The CIA provided the funds via the American Society of African Culture and this link did not become public knowledge until 1967. For all that, Simone was by no means a patriot. She later emigrated to Europe and referred to the USA as the “United Snakes of America.”

[...] I wasn’t going over there to apologize for the racist policies of America.

Which only goes to show how the naive belief that you only need to support the right artists in order to demonstrate the liberty of the West can backfire: One might think that the CCF and CIA might have learned from this experience, yet during the Cold War era the CIA repeatedly intervened in the production of movies, literature and pop – for example, the animated version of George Orwell’s novel “1984” was altered to create a happy end and a victory over the dystopic Communism of the novel seem possible.

An art of misunderstandings

Meanwhile on the other side of the Iron Curtain art was imported and infused with meaning. Sometimes that also resulted in misunderstandings. For example, you might be able to believe that in the 1960s the aim of Rock music was to undermine bourgeois moral notions but in the East this kind of non-conformism would probably not have been possible. After all, for all its rebellious nature Rock was at home precisely in those places where commerce and the rejection of it cannot get by without one another.

[Translate to English:]

Filmposter zu Richard Burtons 1984 Verfilmung, Image via www.imdb.com

Author Salman Rushdie once spread the story that Václav Havel, one-time regime critic and after the Velvet Revolution the last President of Czechoslovakia, had told him of his love of the band Velvet Underground. In the United States in the 1960s the nihilist New York-based band which was managed for a time by Andy Warhol stood for Pop and its abysses, but in Prague’s bohemian scene the band became a symbol for rebellion against the Communist regime (very probably without the support of the CIA). “Why do you think we called it the Velvet Revolution?” Havel is purported to have said.

For many Europeans a whistled refrain is inseparably linked with the fall of the Iron Cur-tain: Of all things the catchy “Wind of Change” by Hanover-based rock band Scorpions, whose lyrics evoke the city of Moscow and who sing about a vague feeling of freedom and unity, became the music accompanying the end of the Soviet Union. True, the Scorpions are virtually unknown on the other side of the Atlantic, but they still continue to fill stadiums in the former Soviet states. And it was been conjectured that the song was commissioned by the CIA: Klaus Meine, the band’s vocalist, wrote the lyrics although he is not known to have penned other ballads.

The Scorpions on their tour in the former Soviet Union, Photo: Lars Wulff, Image via Wikimedia

Patrick Radden Keefe suggests in his podcast named after it, then it was the most successful Pop operation of the Central Intelligence Agency. Incidentally, the singer recently dismissed the claim in an interview with German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Sonntagszeitung but did concede: “If it were the case then it would underscore the emotional power of the music even more strongly.”

Sometimes art becomes a symbol of liberty, sometimes a reluctant ambassador of a system; and the ideological dividing lines and interests are much more complex than simply those between East and West. Which is why Pop music is not a suitable instrument for intelligence work at all. It is universally ambiguous.

If it were the case then it would underscore the emotional power of the music even more strongly.