Joan Miró is an exemplary multimedia artist. The term “multimedia” might, however, initially be misleading. What it calls to mind is “multimedia”, “something to do with the media”, something technical or perhaps sound installations. But at the end of the day “multimedia” means nothing more than working with various media, media that can be quite conventional – music, literature or even the medium that is a wall.

As is marvelously highlighted in the current exhibition “Painting Walls, Painting Worlds”, Miró was particularly fascinated by walls. And music served the artist as an additional source of inspiration. However, there was one thing that Miró loved even more than music, namely literature. Throughout his life he forever had a book in his hand.

Miró’s fascination with literature

There were always books lying around in his studio in Majorca and he started every morning by reading poetry before he went into his studio. It was quite simply one of his rituals. His fascination with literature and especially with Dadaist literature started back in his Barcelona days. It was there, in 1917, that he first met Marcel Duchamp and Francis Picabia. After his arrival in Paris in 1920 he started moving in Dadaist circles again, the same circles as Picabia and Tristan Tzara.

Miró was fascinated by the Dada movement’s understanding of art, with its experimental approach to language. The poets associated with Dada broke language down into its smallest component parts and stripped it of any semantics, before putting it back together, thus raising it to the status of a medium of metaphorical meanings. In short, they deconstructed language.

He investigated “letter poetry”

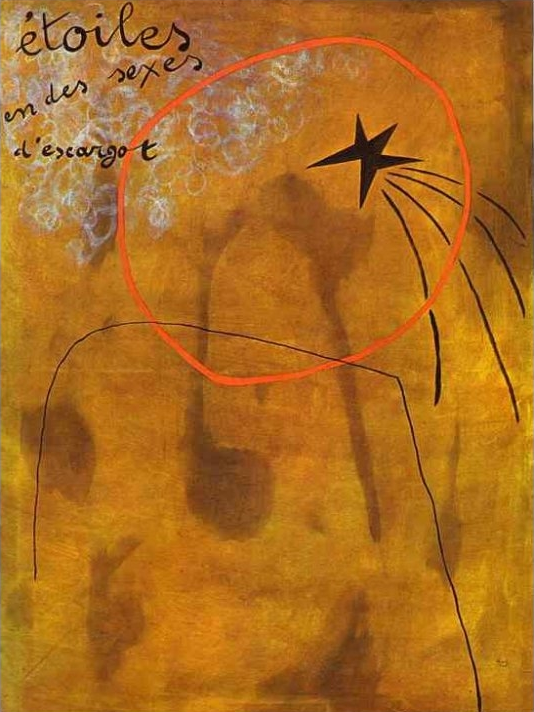

As was also the case with walls and music, Miró devised new ways of working from literature and poetry, allowing himself to be inspired by the latter in terms of colors, shapes and structures. He started writing sounds or words into his pictures. Between 1924 and 1927 he produced a series of something known as “tableaux-poèmes”, an example being “Étoiles en des sexes d’escargot”, which dates from 1925 and is also included in the SCHIRN exhibition.

Joan Miró, Étoiles en des sexes d’escargot, 1925, Image via artemisdreaming.tumblr.com

It was not only on canvas that Miró explored the relationship between image and text. He illustrated poems by Henry Miller, Paul Éluard, Joan Brossa and Tzara and gave his pictures poetic names. He investigated “letter poetry”. And he developed a “vocabulary of shapes” on the basis of the visual representability of individual letters which he was then able to transfer to any technique.

Letters that no longer belong to the world of language

Miró called this invention of his peinture poétique. Like the Dadaists he combined letters in such a way that they became abstract characters. Miró’s letters cease to belong to the world of language and are instead firmly part of the world of images and surface.

Joan Miró, Signes et figurations (gare musée), 1936, Image via pinterest.com

Behind what sounds like a complex theory is actually pragmatism. Miró always rejected interpretation and theorizing. “Je hais tous les peintres qui veulent théoriser,” he wrote to J.F. Ràfols in 1918. His biographer Jacques Dupin wrote in 1961: “He preferred painting to talking about painting, exploring the imaginary in paint to speculating about how best to do this in coffee houses.”

Poems cannot be understood, either

No interpreting and no theory – and in his pictures there is nothing to understand anyway. Miró himself once expounded that his pictures were like poems, something that cannot usually be understood as such either. What is more important is what you feel when you read poems. Or when you look at one of Miró’s pictures.

Miró himself also picked up a pen. When the Spanish Civil War broke out in 1936 Miró was in the small town of Mont-roig in the provinces. He fled to Paris. Since initially he did not have a studio where he could work he started writing. However not in Catalan, his mother tongue, but in French, for him a foreign language. Thus, over the following three years, he produced a poetic oeuvre including calligraphic poems, prose poems in the form of associative concatenations of words or rhythmic poetic verse:

Un oeillet rouge éclate sur le bout d’un parapluie porté par un merlan à queue de perroquet couché sur la neige rose.

Deux grandes dames minces habillées en noir, une longue plume de canari sur le chapeau, sortent du concert.

A red carnation explodes at the end of an umbrella carried by a whiting with a parrot’s nose lying in the pink snow.

Two tall, thin ladies in black with a long canary feather on their hat come out of the concert.

Miró actually painted his poems in his drawing blocks. The writing has something calligraphic about it. And the letters sweep across the picture, tracing lines and arabesques, they resemble figures and create movement and in fact are visual poetry. An artist or a poet? Miró did not believe there was a difference and this understanding of his work links him with Guillaume Apollinaire, that master of visual lyricism. In Apollinaire’s calligrams, writing and images become interchangeable, with writing becoming painting and images poetry.

Miró and literature is a subject that would definitely merit an exhibition in its own right. But what am I talking about – there has been one already. At the beginning of 2015 at the Bucerius Kunst Forum in Hamburg: Miró. Painting as Poetry. Even if it is difficult to go there retrospectively the catalogue is worth perusing!