As described in the first part of this mini series, the Vietnam War caused a great deal of resentment in the American population, and more so the longer it went on. The large number of soldiers killed and the general fatigue felt towards the war by those still fighting in it, military successes by the Vietcong, and the ever more evident futility and hopelessness of the bloodshed led the majority of Americans feeling discontented with their own government, and finally to reject the war.

The Vietnam War was the first war to be broadcast almost live on television day-by-day. The horrors of war and the suffering of the civilian population were transported into living rooms world-wide. If nothing else, the reporting on the Gulf of Tonkin incident, the use of weapons that violated the Geneva Convention, such as Agent Orange or Napalm, or the massacre of My Lay caused opposition to the war and protests. Ultimately, the realization that even the superpower America could be defeated was added to all of this. A protest movement arose out of this situation in the 1960s that was connected by the international political mood, and which was to lend its name to an entire generation, not just in Germany: the protests of 1968.

Vietnam teach-in at universities

The anti-war movement in the US was not just a result of the Vietnam War. It was preceded in the 1950s by the anti-nuclear and civil rights movements, with their ideas being seized and unified by student organizations in the late 1950s and early 1960s. One of the best-known student organizations of the early 1960s was SDS - Students for a Democratic Society, which organized the first Vietnam teach-in at the University of Michigan in March 1965. The organizers expected 500 attendees; 3,000 came. Teach-ins were popular events in the anti-Vietnam War movement, with the largest taking place at U.C. Berkley in May 1965, attended by about 30,000 people.

U.S. Fairchild UC-123B Provider aircraft cropdusting in Vietnam during Operation Ranch Hand which lasted from 1962 to 1971, Image via Wikimedia Commons

Vietnam War protest march in San Francisco, April 15, 1967, Image by BeenAroundAWhile via Wikimedia Commons

Before 1965 one could hardly talk of organized protest. Activists confined themselves to discussions and conversations and the occasional burning of a few military passports. Individual protests had been staged as early as 1963, they grew stronger after the bombing of Northern Vietnam, and in April 1965 the SDS led the first march to Washington, at which 25,000 people demonstrated for an end to the war. An open letter was written to President Lyndon B. Johnson in December 1966, which demanded the end of the war and threatened all youths would refuse to be drafted into military service – they would rather go to jail. Yet the anti-war movement only turned into a national issue in 1967, when 100,000 Americans came together in front of the Pentagon on October 21 to demonstrate against the war. The following year, SDS membership had already swollen to 100,000 members.

Conscientious objectors flee to Canada

The anti-war movement was a student movement first and foremost. The ideas of the movement were considered at the universities, and war, politics and society were examined critically. It was here that organized opposition formed. The protest became ever louder the more the government was forced to draft young men for its military mission in Vietnam. Conscientious objection became a serious problem for the Johnson and Nixon governments. 50,000 conscientious objectors were to flee to neighboring Canada before the war ended in 1974. After the war, compulsory military service was abolished in the US; to this day, the topic remains taboo for both the democratic and republican parties.

President Nixon points out the NVA sanctuaries along the Cambodian border in his speech to the American people announcing the Cambodian incursion, Image by Jack E. Kightlinger (White House Photo Office) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Bascom Hill, 1968, with crosses placed by students protesting the Vietnam War, and sign reading, "BASCOM MEMORIAL CEMETERY, CLASS OF 1968", Image by Dpbsmith via Wikimedia Commons

Even thought the anti-war movement was small, it was very much able to assert itself politically. While the majority of Americans opposed the war from the 1970s at the very latest, only a relative few became actively involved in the protest. What's more, the motivation for protesting was not always the same: Some spoke out against the immorality of the war (The US plowed over a billion dollars a month into the Vietnam War – money that was then lacking back home), others felt the war contravened the American constitution, as it was never officially declared by congress.

The paradoxical side of the protest

There were others who described it as simply being illegal, as it went against the Geneva Conference of 1954. All countries participating in the conference had committed themselves to respect the sovereignty of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. The construction of military bases, the deployment of foreign troops and the shipment of weapons and munition to both parts of Vietnam were banned. But the criticism of the war was also geared towards the US’ own social system, as it was time and again referred to as a war of the working class. Students were not drafted for military service (up until the point at which they, too, were needed due to a shortage of manpower), which for the most part benefited sons of the social class able to afford a course of studies. Paradoxically, the protest movement thus emerged specifically among those who came into contact with the war itself the least.

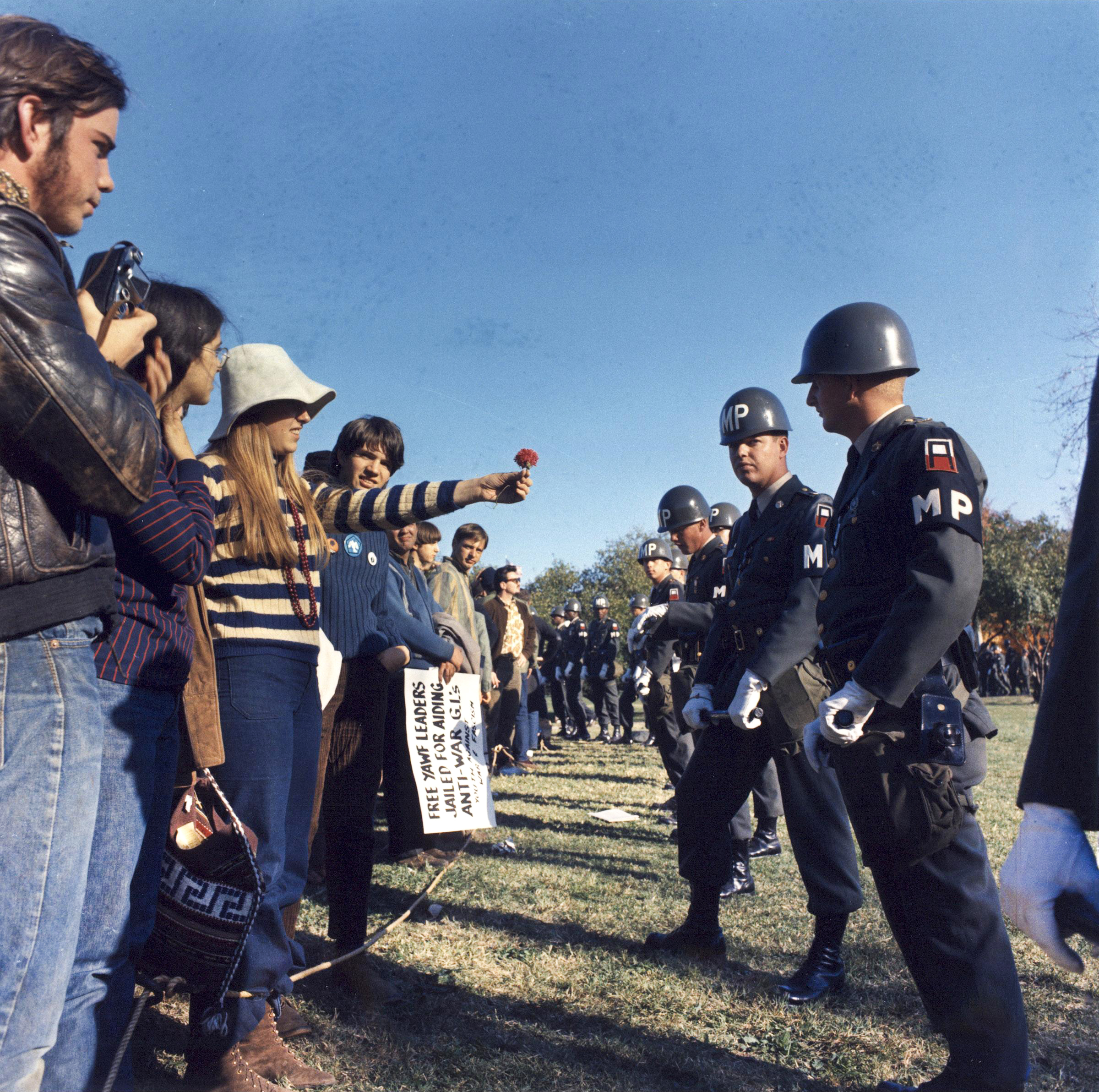

A female demonstrator offers a flower to military police on guard at the Pentagon during an anti-Vietnam demonstration. Arlington, Virginia, USA, Image by S.Sgt. Albert R. Simpson. DoD, DA. U.S. Army Audiovisual Center, via Wikimedia Commons

Anti-war protest against the Vietnam War in Washington, D.C. on April 24, 1971 – at the corner of Pennsylvania Avenue and 10th Street NW., Image by Leena A. Krohn, via Wikimedia Commons

In Germany students also took to the streets against the Vietnam War, and the war became the main concern for the Ausserparlamentarische Opposition (extra-parliamentary opposition, APO for short). In February 1968, the Socialist German Student League held a Vietnam congress under the leadership of Rudi Dutschke. However, the APO’s protests were not solely directed against the US and the Vietnam War, but against capitalism per se. Dutschke was convinced that the US were conducting the Vietnam War on behalf of the capitalist system. Correspondingly, the APO was sympathetic to the communist Vietcong and at protests would chant the rallying cry “Ho-Ho-Ho Chi Minh” after the internationally revered leader of the Northern Vietnamese.

The seeds of left-wing extremism

The media, in particular the conservative Axel-Springer-Verlag and daily newspaper BILD, treated the student movement with contempt. “Radicalists,” “political rowdies,” “red guard” or “academic storm troopers” were just a few of the headlines used to disparage the demonstrating students. Rudi Dutschke was labelled Public Enemy No. 1 and public opinion was further inflamed by a pro-American demonstration, called for by the Berlin Senate two days after the APO’s Vietnam rally. In this atmosphere Rudi Dutschke was gunned down on April 11, 1968 in front of the office of the Socialist German Student League. He survived, grievously injured. The assault on Rudi Dutschke marked a turning point for the APO and German history: members radicalized and later joined the extreme-left terrorist Red Army Fraction, who were willing to resort to violence.

Paving stone with Buttons "expropriate Springer", 1969, Photo: Andreas Praefcke (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Gaston Salvatore and Rudi Dutschke at the Vietnam Congress of the SDS (Sozialistische Deutscher Studentenbund) 1968 in West Berlin. Image via bpb.de