The High Line is already packed. Spring is in the air today and people are flocking like moths to the flame to the famous green space elevated one story above ground level on an old railway track. The air is still crisp and there is a gust of wind every once in a while, but the sky is blue and the sun almost strong enough to warm the face. The crocuses are out and the first light-pink buds are already on the bushes along the old tracks.

The mural on 22nd Street is brand new and seems a bit like an omen of things to come: “I lift my lamp beside the golden door” depicts three vibrantly dressed versions of the Statue of Liberty, one tear trickling down each of their faces. Between them one can read the last verse of Emma Lazarus’s famous poem “The new colossus”, engraved into a bronze plaque attached to the base of the real Lady Liberty. The Berlin-based artist of the mural, Dorothy Iannone, chose these three versions of the port of entry for so many immigrants in the past to “bring a bit of joy to an often exhausting and demoralizing political debate.”

Rise and Resist

From here it is just a short walk along the tracks, which are still visible on the High Line, to the cute cobblestone streets of West Village, where I’m going to meet Katie Holten to talk about her project “She Persisted”. It is part of the POWER TO THE PEOPLE exhibition now on view at SCHIRN KUNSTHALLE FRANKFURT. The first signs of Holten’s studio are literally two signs in the basement window. One says “Facts matter”, facts in red and matter in blue, and the other reads “Resist” in black Sharpie on brown cardboard.

There is a click, the red painted door swings open, and the artist sticks her head out, a friendly smile on her face. She is wearing black boots, jeans, and a gray V-neck T-shirt that says “Immigrantes bienvenidos aqui” (Immigrants welcome here) on the front and “Rise and resist” on the back. I enter the basement and walk through a narrow hallway, illuminated only by a single naked light bulb and with lots of pipes and electrical lines running overhead. Holten leads me to the first door on the right.

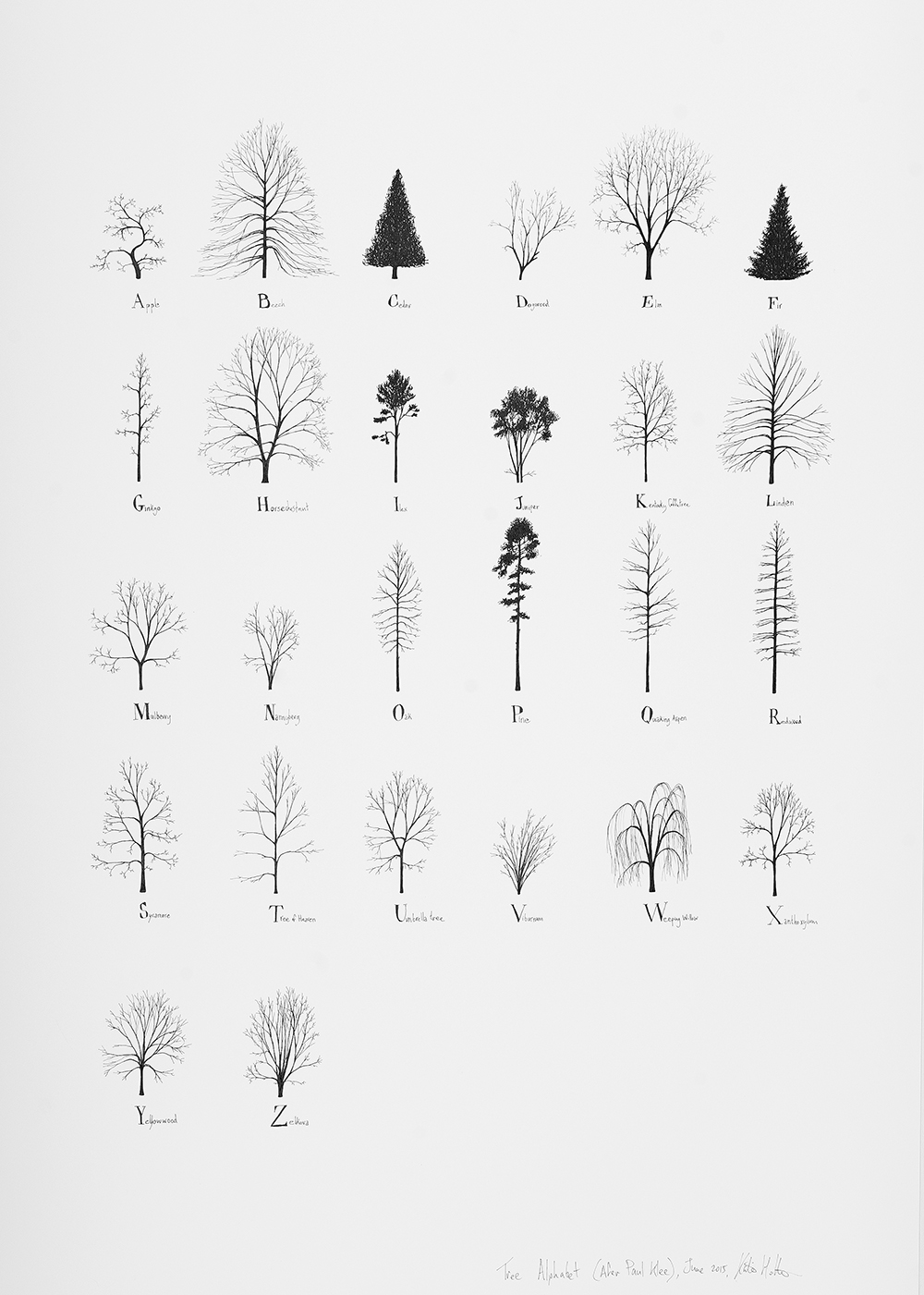

You enter the studio through a small room mostly used for storage – there is a Strand Book Store bag, a pile of magazines and papers, and pencils everywhere. The floor is dark-green carpet and the ceiling, typical New York, is completely tiled. “I’m sorry, I just got back from a residency in France and haven’t unpacked the studio completely. Also, the guy I sublet the place to threw away my chairs.” Her main work space is in the adjoining room. One huge desk holds papers, drawings, and books. There is a small magnetic board leaning against the wall with the first prototypes of a new tree alphabet, which she is working on together with the NYC Department of Parks and Recreation using real trees of NYC.

Peppermint tea and chocolate

By the front windows is another small, more temporary working area with a wooden board on a trestles. But it is something else that mesmerizes you as soon as you enter the room: The wall on the right is almost completely covered with black chalk paint and on it white chalk drawings of circle after circle after circle. “It’s the universe.” Holten explains. “It’s the shape of the universe. It is a time-lapse drawing – you see it at the very end. The drawing started off as a tiny acorn, then turning into the Earth, the solar system, the universe, and a tree. It’s for Emergence and somehow they’re going to make it digital.” She sets me up with a cup of peppermint tea (“People keep bringing me tea, because I’m Irish I think...”) and some chocolate. We sit down at the front windows, Holten on the windowsill and I on the only remaining chair she brought from home.

People keep bringing me tea, because I’m Irish I think..

Katie Holten came to New York 14 years ago for a Fulbright Scholarship at Cornell University. She was born and raised in rural Ireland; her mother is a gardener. The main focus of her work has always been, and still is, trying to understand the relationship between humans and the environment around us.

“Growing up in the countryside, I was fundamentally aware of the life cycle. Especially because I was born in 1975. In the late 1970s and 1980s we still didn’t have that much that was imported. Well, all of our meals were one potato, one veg, one meat. That was the classic Irish meal. I remember getting milk directly from the creamery at the farm. We grew our own vegetables. We composted. So I literally saw the cycle of how everything is connected. In a city you’re removed in so many ways from that cycle. So it just felt like I needed to spend some time in a big, urban environment to see what that is like.” That was when she came to New York and, like so many others, just got stuck.

She found herself in the center of the East Village missing those green hills of Ireland. A friend of hers gave her the book “New York City TREES: A Field Guide for the Metropolitan Area” by Edward Sibley Barnard. She pushes her wavy, elbow-length hair out of her face and laughs: “I remember rolling my eyes at him and thinking: New York City and trees, sure, but I ended up using it then and I’m still using it now.” She hands me the well-thumbed copy with lots of light-yellow Post-its sticking out everywhere.

How to write with trees

“The tree drawings simply came about as a way to make maps of the walks that I was doing. I was using the street trees as markers. And about ten years after I started I realized I could actually use these and turn them into letters, so they could speak for us.” Eventually, she turned her tree drawings into a free font that you can download. So everybody could use trees to communicate and get a new sense of the words, like ‘nature,’ for example, which we’re so sure we already know everything about. This was before 2016, and then the election happened and things fundamentally changed in Katie Holten’s approach to life and art.

So it just felt like I needed to spend some time in a big, urban environment to see what that is like.

Katie Holten, Tree Alphabet, 2015, Image via: katieholten.com