Mister Weisshaar, what was your most beautiful walk to date?

That’s a tough one. The most outstanding walks were those in the open-cast mining world of Golpa-Nord, also called “Ferropolis”. Walking along the bottom of the open pit, which later was flooded. For three or four years I offered guided walks there. It was so absolutely unusual, and I haven’t experienced anything like it since.

What constitutes a good walk to your mind?

Perhaps arriving somewhere quite unlike where you had expected to be. Because along the way, for example, you simply felt like walking in a particular direction and let yourself be led by what happens along the way. In that context, you can also consider what terrain you actually choose for your walks, whereby usually it is parks, pedestrian zones, or the outskirts of a village. Then there are areas where you walk less frequently: through industrial estates, past a sewage works, or the interstate, to name but three. Insights from Walking Studies also suggest, in fact, that it is even rewarding to go for a walk there, too. Because by walking you get a representative idea of the world in which you live, and those places are quite simply part of it.

Do you prefer to walk in town or in the countryside?

What I find exciting are those districts or areas that you can’t really define exactly what they are: Town or countryside? Here in Leipzig, there are many places where you could say you are in town but you are also just as much in the countryside.

To go for a walk or a stroll is a conscious decision, perhaps one also chosen instead of other forms of transport. So what is it that fascinates you about walking?

Walking gets you closest to the world. The way we move also determines our perception and our understanding of the surroundings. As soon as I use a means of transport, I am dependent on the paths or routes that particular form of transportation uses or is allowed to use; I can reach more or less everywhere by bike, but some paths can only be traversed by foot. If I move by car, then I have to drive on a road, and in a high-speed train everything rushes past me too quickly. When walking you move at the speed we are born with, your brain is able to keep pace with the sensory impressions; the faster you move, however, the more you overlook sensory impressions in order to be able to perceive anything at all. Walking, by contrast, is direct and a sensory experience.

In your book “Einfach losgehen” (Simply set off) you write: “An insight gained when walking is of great value.” Why is it easier to think when walking? Why do I have the best ideas when under the shower or out for a walk?

Brain researchers say that the right lobe of the brain directs the left lobe, and vice versa, without us having to do anything. When walking both lobes are involved, and we find ourselves in a state that favor new linkages in the brain. Another explanation is that you can work and walk at the same time, because you can’t writer or read while walking. But you can go through in your mind everything that has happened during the day. If you’re not under pressure to produce results then you will probably be more relaxed thinking: That previous mental block now dissolves.

You enrolled in “Walking Studies” at the University of Kassel. What exactly is that and what is it that gets researched?

Lucius Burkhardt developed Walking Studies in the mid-1980s in Kassel, as part of the Dept. of Architecture, Urban and Landscape Planning. Essentially, the focus is on how we perceive a city when we walk through it. Architectural planning is always about space, about the three-dimensional elements in it and the speed at which we move in it. In order to understand the spatial context of a city you need to be moving around in it; it is not enough to read books about it. What happens at an intersection, for example, cannot simply be entered on a map; you have to study it on location.

Walking Studies is part of the Dept. of Architecture, Urban and Landscape Planning. Is it factored into these fields? Pedestrians tend to have a somewhat small lobby.

That’s true, but it’s growing! Take the non-profit “Fuss e.V.” for example, and I’m an active member. It launched the project “Gut gehen lassen – Bündnis für attraktiven Fußverkehr” an initiative for making pedestrian life more enjoyable – and open to cities, too. Here in Leipzig we meet the lord mayor once a year and go on a walk through town and look at things from a pedestrian’s perspective. This is crucial as the members of the city council tend to drive most places by car.

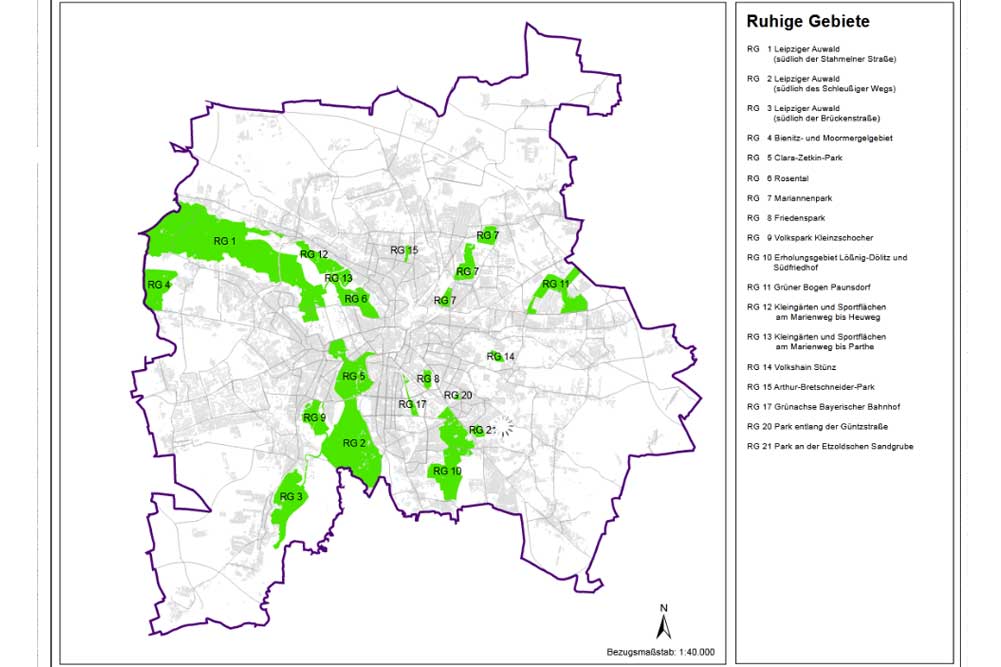

Parks in Leipzig, image via l-iz.de

Let’s take the example of Leipzig, where you live: How pedestrian-friendly is the city?

The city was mainly built between 1870 and 1930 and is very compact. There are lots of buildings from the end of the 19th century with wide streets and sidewalks. In most districts you can therefore really enjoy walking. A major problem is the backlog of modernization work on the sidewalks: If a road gets modernized, then it tends to be the lanes that get renewed, but not the sidewalks. That sadly the fact in many cities. Over the last ten years, Leipzig has, moreover, grown very fast, and there are ever more cars in the streets, and they are increasingly parking on the sidewalks.

What must a city have to be optimal for walking?

Since the pandemic started, many have discovered walking. Because more people are now out and about and keeping their distance from one another it has become clear how narrow sidewalks actually are and that the city’s parks are completely over-filled. Conversely, this show that we have too few green spaces. Here in Leipzig the inhabitants were at times asked not to go to the parks on Sundays because they were simply too full. Talk about pathetic! Slowly that has prompted a rethink; years ago, people were forever complaining about the lack of parking spaces, and now the call for more space for pedestrians is becoming ever louder.

After two years of pandemic, many are tired with walking, to which various annoyed articles in the arts pages of late. In your opinion, how much has this impaired this form of movement?

I am of the opinion that the image has actually improved. Of course there are some who moan that they are forever walking the same route round their district. But even young people now meet to go for a walk together. Many people have noticed that you don’t need to prepare in order to go for a walk – and I believe they will not forget that. And walking not least of all has a beneficial effect: If you walk a lot each day you’re also doing something for your health into the bargain.