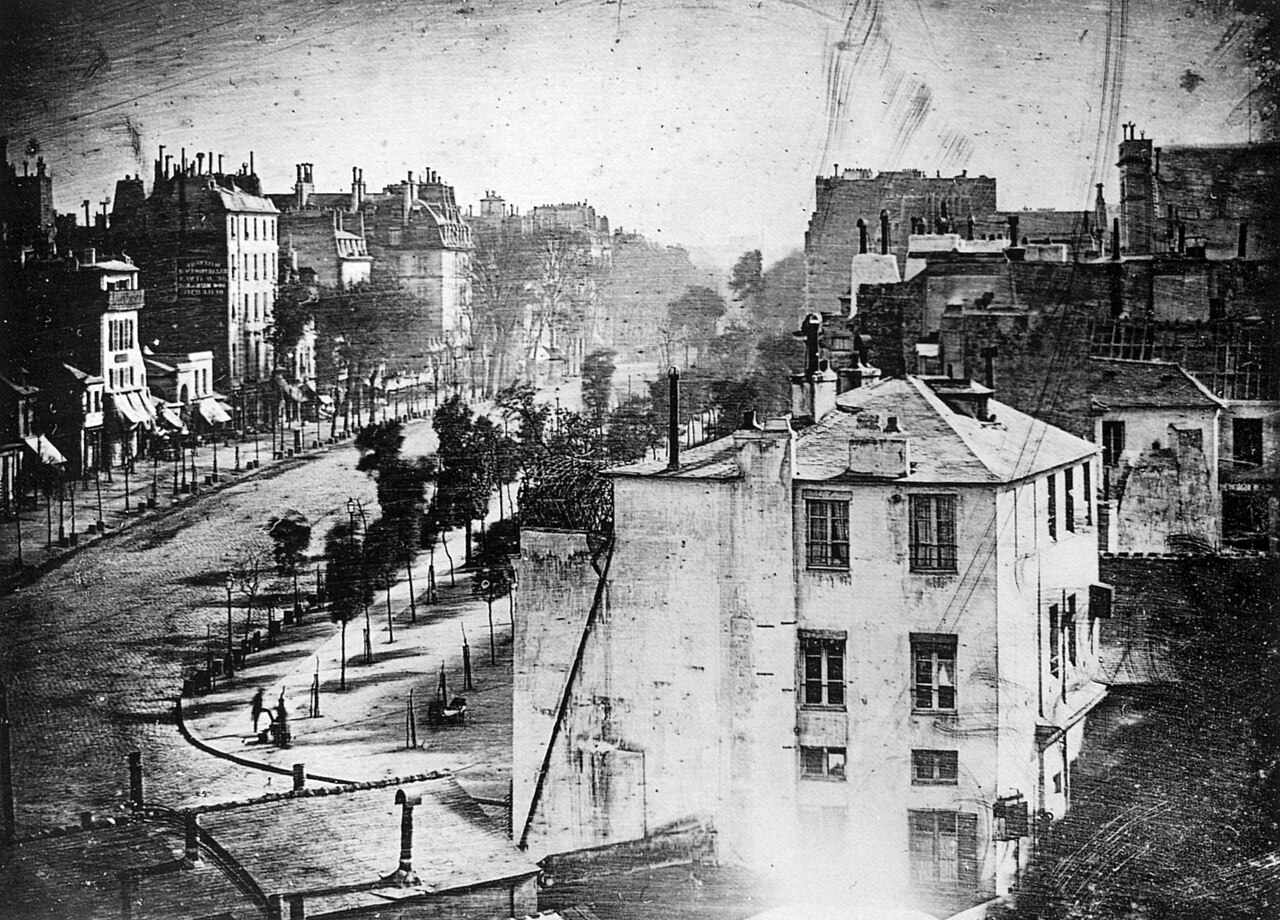

One of the first street scenes to be captured in a photograph is almost 200 years old: Thanks to the daguerreotype we now know exactly what it looked like on the tree-lined Boulevard du Temple in Paris’ 3rd District in 1838 or 1839. The same goes for the 1920s in Berlin, the ruins of Delhi from 1910, or the overcrowded Mulberry Street in New York City at the turn of the century – all are captured and documented either in photographs or even in moving images.

And the first sound recordings of a city? They are not even a few decades old! In 2010 The Atlantic staff writer Alexis C. Madrigal wrote an article for the magazine entitled “The Quest to Find the First Soundscape”. Initially he didn’t find any. And the shouting newspaper boy typical for films from around the 1910s and 1920s in the metropolises of the western hemisphere was ultimately only something produced in the studio.

What did New York or Paris sound like at the turn of the century?

The fact that until fairly recently an auditive collective memory was not feasible largely had to do with the technical difficulties of making sound recordings. Thomas Edison’s phonograph that enjoyed such a rapturous reception in 1877 itself produced such strong vibrations that any recordings made using it were comparatively quiet. It could only be used to record very strong sound signals. Similarly, various successors were more suited for recordings made in sound studios rather than in the hustle and bustle that prevailed in cities and on pavements. In fact, nobody can know for sure what it sounded like around the turn of the century in New York’s Mulberry Street or in 1838 on the Boulevard du Temple in Paris. Nonetheless, those soundscapes that have survived from the era of early sound technology are primarily orchestrated sound snippets.

Street view of Paris (Boulevard du Temple), Daguerreotype by Louis Daguerre, 1838, Image via wikimedia.org

Mulberry Street, New York, 1900, Image via pinimg.com

It was not until the early 1970s that this changed fundamentally when Canadian avant-garde composer, music theorist and professor R. Murray Schafer established the “World Soundscape Project” (WSP) with a group of students from the Simon Fraser University in Vancouver. And interestingly the systematic recording and cataloging of acoustic landscapes was originally merely a spin-off of a totally different undertaking: Schafer, one of the pioneers of so-called acoustic ecology was irritated by what he saw as the increasing “noise pollution” of urban habitats. Roaring, buzzing and whooshing sounds form the soundscape of our modern everyday lives. With his own university seminar Schafer wanted to create an awareness for a phenomenon that affected everyone.

Such a recording did not yet exist

Apart from the acoustic overlaying of our everyday life Schafer and his students also addressed the general change of those sound landscapes. Or put the other way around: They explored what the change in our habitats sounds like. Which takes us back to the starting point. After all, never before had there been such a systematic recording and archiving. Initially, the group’s members armed like field researchers with microphones and recording devices began to record their immediate surroundings. “The Vancouver Soundscape” was followed in 1973 by “The Soundscapes of Canada”, which involved Bruce Davis and Peter Huse travelling around the entire country. Later their findings were broadcast under the same title as a radio series for CBC Radio.

And from the start the sound researchers were not bent on producing an arbitrary and subjective composition, but rather aimed for as categoric as possible a recording of acoustic surroundings that could be experienced in line with criteria such as rhythm & tempo, language, gestures and textures or the alterations in the changing soundscapes. The growing attention and support enabled ever more longer recording trips: Finally, in 1975 Schafer and his students went to Europe to record the sounds of the large metropolises. During their stops they also gave talks on the concept of a global soundscape project and quickly became an inspiration for others. But the focus was not only on large cities: In Sweden, Germany, Italy, France and Scotland the Canadians also chose a village to record including Bissingen in Bavaria where the acoustic researchers captured the blacksmith’s rhythmic hammering.

Available for more and more people thanks to the smartphone

The ultimate end and climax of Schafer’s work was in 1977 “The Tuning of the World”, a global soundscape project as the title reveals, while one year later his colleague Barry Truax presented the first standard work on the topic entitled Handbook for Acoustic Ecology. At least in the last ten years it is no longer possible to talk about a lack of acoustic documents: Thanks to the smartphone an increasing number of people now have access not only to visual but also acoustic recordings and in a reasonable quality. Vancouver remains an important center for sound ecology and acoustic research but meanwhile the methods and approaches that began here are now practiced the world over.

Soundscapes of Canada, WSP recording setup at Westminster Abbey, Mission, BC, June 1974, Image via www.sfu.ca

Pitches of predominant hums heard in Skruv (Sweden), originating from the factories and the shopping centre, Image via britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk

Today, you can listen to a 15-minute soundscape of Frankfurt’s Port Railway or a rainy day in Xiamen, China; you can explore the acoustic mapping of entire cities from the comfort of your sofa or experience a soundwalk on Times Square in New York. Moreover, soundscapes and soundwalks are also integrated into artistic installations or exhibited as stand-alone works.

However, we are still a long way off from a categoric recording of the acoustic status quo, since as a result of the increasing number of documents that are stored somewhere between YouTube, private blogs and the archives of university libraries the situation is getting more and more confused. But should somebody one day embark on the mammoth project of a global evaluation to show how the acoustic world alters in the respective corners of the earth from month to month, year to year and one decade to the next there would at least already be sufficient material for it today.