When I think of lakes in art, the first image that comes to mind is this: a lake surrounded by dense reeds, with trees close to the water’s edge that leave it in darkness. A simple wooden jetty protrudes from the thicket of reeds out across the water, and between the jetty and the surface of the water, almost floating in the air and perfectly poised for the dive, is probably the most blissfully happy pig in the history of art.

“Köhler’s Pig”, created by Michael Sowa, has been hanging in the air for more than 20 years. It is inconceivable that it could ever land. But after my initial delight at this lake scene, I feel the skeptical gaze of the limnologists (limnology is the science of the lake as an ecosystem) on me. Could this perhaps be a pond? It’s hard to say; the body of water in Sowa’s painting is not, in fact, large. A commonly used definition of a lake – as opposed to a pond – states that a lake must be over two meters deep to merit the name. A pig is not exactly lightweight. What if the water isn’t deep enough? It’s hard to imagine this pig ever landing!

Michael Sowa, Köhlers Schwein, Image via pinterest.de

More than two meters’ depth

Whether or not Melike Kara has ever dived into a lake we do not know. Nor do we know the real depths of her installation “shallow lakes”, which is on show in the SCHIRN rotunda until May. I see the faces of the limnologists before me once again. On the other hand, who really cares about the actual depth of Kara’s work when it leads to much deeper intellectual levels than two meters would ever allow? “Shallow lakes” is complex and consists of various elements in the exterior and interior of the rotunda. On the ground outside, she has installed five 32-cornered shallow sculptures. They appear like bodies of water, small lakes, or large water lily pads. Between them, as if they were reeds, five octagonal pavilions rise up into the air, their fabric roofs reaching up to the first floor of the rotunda and printed with pale black and white portraits. Climbing up the metal poles of the pavilions are small plaster flowers. In the interior hang abstract paintings in grey, white, red, and pink, alongside further portraits, as if they were the flowers of the installation, lifted out of the water by the reed-grass pavilions.

Writing about lakes in terms of cultural history turns out to be a surprisingly difficult endeavor. Perhaps I am hampered by my lack of experience with lakes. I have never in fact swum in a lake and have therefore never dived into one either. It just hasn’t come up. And so I’m not sure what I’m actually trying to find out. As a first point of reference, I take art history. Yet my mind is not exactly flooded with depictions of lakes. As a first step, I consult my search engine of choice, and the results are sobering. Where I do find a lake – and not “the lake” – depicted, then it’s in a Bob Ross style. My screen is tiled with neon-pastel, romantically kitsch lake views. Mountains in the background, or perhaps just one mountain in the middle, are a popular choice. The landscapes are generally deserted, with only a log cabin or ruin on the shore bearing witness to (former) civilization. Trees in autumnal shades of red, suns setting and coloring the sky red, pink, and orange. Milky moons reflected in the water, provided the mist does not prevent this. Where is Caspar David Friedrich when you need him!

A short art history of the lake

After some searching, I find him at Sotheby’s. His painting “Landscape with Mountain Lake, Morning” (painted between 1823 and 1835) was sold there in 2018 for 2.5 million pounds. It’s an amiable scene: We see the mountains in the background through the morning haze, a few wafts of mist still lingering on the shore. In the foreground is a lush, green, hilly meadow, not yet fully caught by the sunlight. Three cattle are standing in the hollow (the two brown ones are enjoying the view of the lake, while the black one isn’t interested in the water) and a hiker or shepherd is standing a little higher to their left. Typical Friedrich, one man alone with nature. Less typical, however, is the subject, since the artist was much more devoted to the sea.

Bob Ross Painting, Image via painterslegend.com

Caspar David Friedrich, Landschaft mit Gebirgssee, Morgen, Image via commons.wikimedia.org

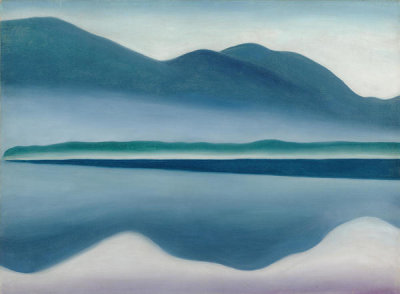

In the tile view of my image search, one work stands out: Georgia O’Keeffe’s “Lake George” from 1922. The dark blue silhouette of a mountain range stands out against a light blue sky. In the foreground is the lake, the smooth surface of which reflects the mountains so they match almost perfectly. The composition is intersected horizontally by a narrow strip of green shore. We always associate Georgia O’Keeffe with the arid landscape of New Mexico, but before she moved there permanently, she spent her summers at Lake George in the US state of New York for over ten years. The family of her partner Alfred Stieglitz had an estate there.

O’Keeffe’s somewhat younger contemporary Ansel Adams also became famous for his depictions of landscapes. His black and white photographs, mostly of the national parks of the American West, often feature lakes. Not infrequently, their sole purpose seems to be to reflect the spectacular landscape that surrounds them: Mount Kaweah is reflected in Moraine Lake, Mount Watkins in Mirror Lake in Yosemite. At the same time, thanks to their mirror-smooth surfaces, the lakes are a visual haven of calm in the midst of a varied and turbulent landscape. Or they form a compositional antithesis to huge mountain massifs, as in “Mount McKinley and Wonder Lake” (1947). In the background is the bulky, snow-covered mountain, in the foreground the lake: a shining silver surface in the middle of a deep black landscape, with hardly any structure and no depth, appearing artificial. The lakes in Adams’ photographs are not the main focus, and yet the compositions would be so much poorer without them. Rather than playing the supporting role, they are the supporting act. The USA is where we find some of the largest lakes in the world: the Great Lakes in the north of the country, some of which extend into Canada.

Georgia O'Keeffe, Lake George [formerly Reflection Seascape], 1922, Image via prints.okeeffemuseum.org

Ansel Adams, Mount McKinley and Wonder Lake, 1947, Image via anseladams.com

Limited visibility between facts and kitsch

There are 1.4 million lakes in the world that are bigger than ten hectares. Of these, 900,000 are in Canada, making it the most lake-rich country in the world. A further 200,000 are in Finland – so there aren’t many left for the rest of the globe. The world’s largest lake is the Caspian Sea (393,898 km²), whose name invites a brief digression into a linguistic phenomenon: In Low German, as in Dutch, the word “See”, meaning lake, refers to what is clearly a sea (as in “Nordsee”, the North Sea, or “Ostsee”, the Baltic Sea). In the interior of northern Germany, meanwhile, the word “Meer”, meaning sea, is used for lakes like the Steinhuder Meer, Engelsmeer, and Grosses Meer. Language is so fascinating! But back to the matter at hand: The deepest lake in the world is Lake Baikal in Russia (1,642 m); the highest is the crater lake of the Licancabur volcano (5,920 m) on the border between Bolivia and Chile. The lowest is the Dead Sea (420 m below sea level), while the lake with the clearest water is Rotomairewhenua / Blue Lake in New Zealand with a horizontal visibility of between 70 and 80 meters (for comparison: distilled water in laboratories has a visibility of 80 m). There are hidden lakes lying kilometers beneath the Antarctic ice.

Caspian Sea, Image via geo.de

Ice could take us back to art history, to Dutch painting in the 17th century, when frozen lakes and the socializing that took place on them were a very popular subject. We could also look to Symbolism, to Ferdinand Hodler’s paintings of Lake Geneva and Lake Thun. Gustav Klimt painted Lake Attersee and Akseli Gallen-Kallela painted Lake Keitele in Finland. It is easy to describe individual depictions of lakes and to reduce the majority of internet search results to kitsch. Then you’re merely skimming the surface. The fact is, just as in the tropholytic zone of the lake – where the water becomes cloudy, hardly any light arrives, and photosynthesis is impossible – I too encounter limited visibility beneath my mental surface. What am I searching for? I want the lake to tell me something. But what?

The archive as a metaphorical lake

After some pondering, I find that Melike Kara’s “shallow lakes” actually tell me a lot. Above all, why it always has to be shallow, never deep. In her work, Kara deals with her Kurdish and Alevi roots. She works with archive material and has spent years building up her own visual atlas in order to keep the culture, tradition, and history of her people alive. From the depths of an archive, she brings stories to the surface. Are archives not like lakes? The deeper you sink into the lake, the darker it gets. The longer stories slumber in archives, the greater the danger that they will be forgotten. But archives need to live, they need light and oxygen to be able to continue telling their stories. Metaphorically speaking, this is only possible in a “shallow lake” where sufficient light and oxygen is available.

Ferdinand Hodler, Genfer See mit den Savoyer Alpen, Image via kunstkopie.de

And as if the dam has broken, with the help of Ansel Adams I realize something else. When we look at a lake, we don’t see the lake itself but the reflections and mirroring of its surroundings. We don’t see the closed “lake” ecosystem. The still surface of the water is like a sheet of glass that reflects outwards and conceals what lies beneath it. In fact, the lake is what we project into it, rarely revealing what it actually is – namely, a depression in the earth filled with, to put it simply, fresh water (mostly), aquatic plants, algae, plankton and, ideally, fish. How unromantic!

A little lake has the perfect dimensions to provide fertile ground for our imagination. And on its shores, our notions of romance, idyll, mysticism, fantasy, and the unearthly all combine. The moon, the log cabin, mist, and ruins – remember them? The seeming infinity of the sea cannot create an idyll, but the more manageable lake can. Raging waters teach us to fear, but do not fire our imagination. For this, we need still water, a small body of water like those we see in the rotunda, because they run famously deep. Scotland’s Loch Ness has been scanned again and again over the decades using the latest technology, and no primordial creature has been found. And yet we want the mysticism, we want to believe in Nessie. I, for one, will never dip a toe in that water. And just as Nessie is undoubtedly real, somewhere above a lake I don’t know there hovers a blissfully happy pig.

.