When I was planning a holiday in Morocco in February, several people told me not to bother with Casablanca. The attraction of the country was its ancient cities, they said, not its modern ones; I should sidestep the capital, Rabat, and the commercial centre, Casablanca, in favour of Fès and Marrakech with their ancient, and specifically Moroccan medinas and palaces. In the event, I used Rabat as a base, enjoying its combination of old and new buildings, spending two days in Fès and finding one day for Casablanca, ignoring all advice. I’m very glad I did.

Michael Curtiz, Casablanca, 1942, Film still, Image via telegraph.co.uk

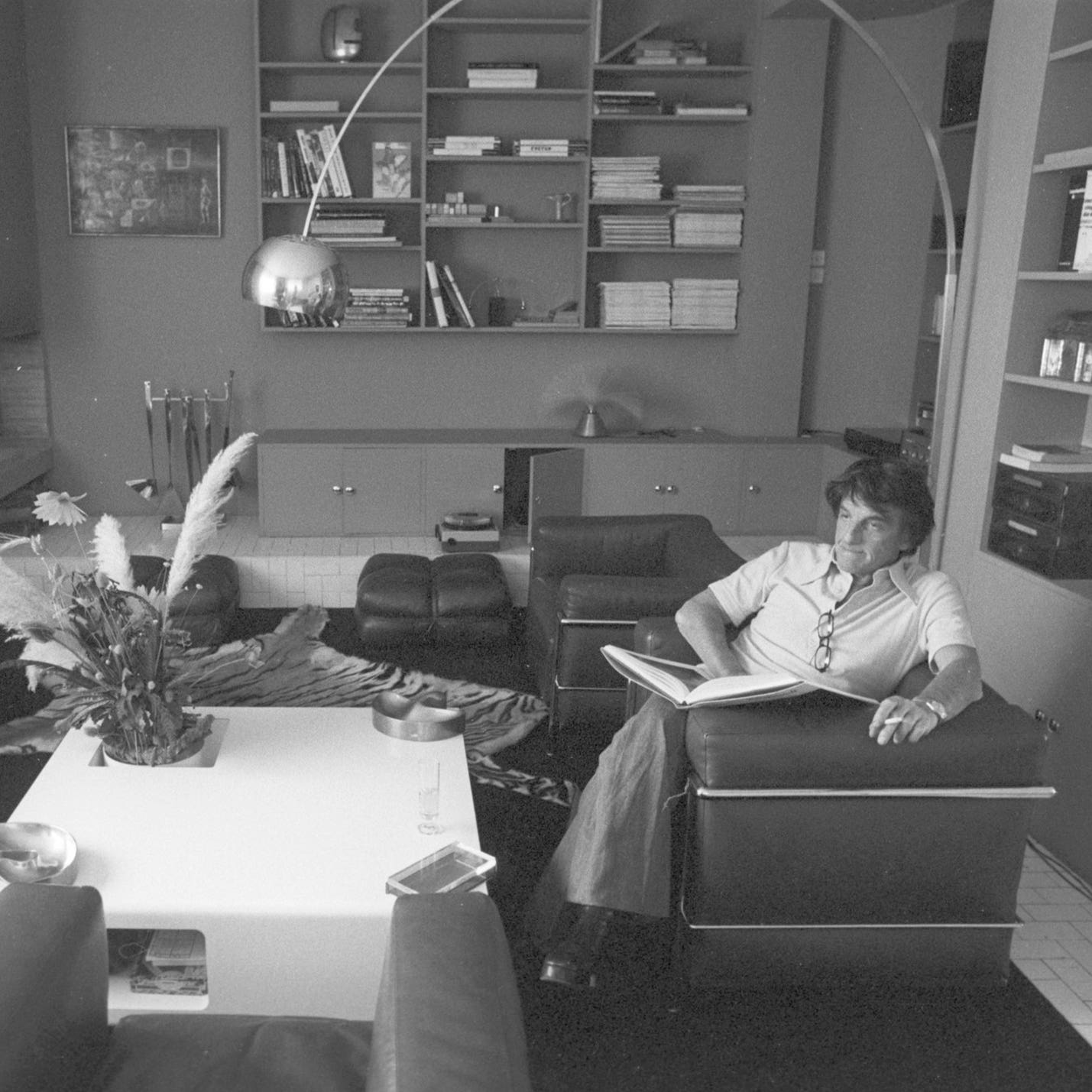

Dr. Georges Burou, Image via independent.co.uk

Before visiting, I had two associations with Casablanca. The first was Michael Curtiz’s 1942 movie, famously not filmed anywhere near the city, nor with any Moroccans involved, although several restaurants and bars claim to have inspired Curtiz, and Rick’s Café, based on a fictional one in the film, opened in 2004. The second was more personal to me, as a transsexual woman: Casablanca became internationally famous for sex reassignment surgery after Georges Burou opened a clinic there in the 1950s, operating on April Ashley, Coccinelle, Jan Morris and others. But Burou and his clients are long gone, and Curtiz was never there. Nowadays, Casablanca does not entrance Westerners so much, precisely because it seems so European, with its layout designed and its centre built by the French colonialists, who used it as their main port – and as a blank canvas for many of their modern architects, who built around and over the existing 19th century city.

Bik Van der Pol, School of Walking, Film still, Image via schoolofcasablanca.com

Since Morocco gained independence in 1956, its citizens have added plenty to their French inheritance and carried stories from the anti-colonial struggle into the 21st century – as can be seen in the video series “School of Walking” by the artist duo Bik Van der Pol, which document different guided tours (or derives, in the Situationist parlance) through the city. For the three videos, which are on display in the publicly accessible SCHIRN rotunda until October 12, Bik van der Pol collaborated with contemporary artists and cultural producers, who portray Casablanca as a modern city and creative centre, where the generation of artists of the 1960s and 1970s developed their dreams of a common future.

A Deep Dive into the architectural history of Casablanca

Architect Imad Dahmani is the co-founder of MAMMA, dedicated to Moroccan architecture, art and urbanism, and his video takes us to the heart of the French colonial city. Dahmani starts at Mohammed V Square, where urban planner Henri Prost, commissioned by military governor Hubert Lyautey to design a new Casablanca, decided to concentrate the city’s administrative buildings. For the City Hall, Court House, Post Office and Central Bank, Dahmani points out, the architects opted for a Neo-Moroccan style, incorporating elements such as the ceramic tiles found in the city’s traditional medina into their modernist works. Among other masterpieces, he highlights Marius Boyer's Wilaya building (1928-39). Originally planned as a hôtel de ville (town hall), it now serves as the seat of the regional government and combines traditional North African designs with a flat roof and modern clock tower. The overall effect of this central collection of institutional buildings, taken over by successive Moroccan governments after 1956, is important – it gives a sense of the city and the country as a modern economic power, allowing the official capital, Rabat, to remain smaller, more traditional, and more attractive to tourists.

Place Mohammed V, 2014, Photo: Rigelus, Image via wikipedia.org

The former Catholic Église du Sacré-Cœur in Casablanca © Mitzo / Shutterstock, Image via easyvoyage.com

Opera house in Casablanca, designed by Christian de Portzamparc, image via jet-contractors.com

The question of how to add to the colonial legacy around Mohammed V Square is a live one: as his tour starts in the Arab League Park, opened as Parc Lyautey in 1913, we see, but do not hear about the phenomenal Art Deco-style Sacred Heart Cathedral, designed by Paul Tournon and opened in 1930, and used as a cultural centre since the French were ousted. Dahmani does explore the Opera House, built opposite after French architect Christian de Portzamparc won an international competition in 2012. I wish I’d had Dahmani to walk me around when I was in Casablanca: seeing the buildings was one thing, but I would have loved to have known more about how rigorously the city was planned, In particular, it was intriguing to learn that locals were so attached to their conception of Mohammed V Square that de Portzamparc putting the Opera House’s fountain directly opposite the Square’s was seen as undermining the Square’s original design, even though its fountain was only built in the 1980s.

Dahmani explores something that can easily be observed on arriving at Casablanca: Prost made a conscious decision to separate the medieval and modern cities, building another square, the Place du France (now the United Nations Square), to separate the old medina from the French developments. He takes his audience to Avenue Hassan II and the Mohammed V Boulevard, showing them various modernist, Art Deco and Brutalist buildings – all white, all three or four storeys, but with extraordinary architectural variety within those parameters. The cinemas are especially interesting: Casablanca was renowned for them, with 300 at one point – appropriate, then, that Curtiz so memorably wrote the city into film history. Since independence, the most notable new building reflects a change of emphasis, but a continued French influence: the Hassan II Mosque, completed by architect Michel Pinseau in 1993 and built near the medina, on the seafront, by Moroccan artisans.

Insights into street art tradition and everyday culture

Nabil Qerjij tells a more bottom-up history, looking at how Casablanca’s urban environment has provided a huge canvas for graffiti artists such as himself. He points out the long heritage, talking about Ahmed Bouanani’s travelogue film “6 et 12” (1968), in which tags are visible on a wall, and that artists travel from the United States or Ukraine to writes their names into the city. He laments the corporate capture of this culture, in the form of a street art festival that did not invite local graffiti artists to participate, nor offer any workshops for them with visiting artists. This promotes “the idea that you need authorisation and good technical ability,” Qerjij tells his audience, “and kills the democratisation of expression”.

Hassan II Mosque, completed by Michael Pinseau, 2014, image via tripadvisor.de

Street Art by Machima, 2020, image via wecasablanca.com

The beach of Mohammedia, Image via barcelo.com

That democratic expression is central to Maria Daïf’s video, where she walks along the beach, talking about how men play football and women pray, and how its closure during the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted its role in making Casablanca so vibrant. Watching it, I wished I’d been able to stay longer and explore more. In the event, I only had half a day in Casablanca: I’d hoped to see Raja AC, one of the biggest clubs in Africa and another product of the resistance, play that evening, but the Mohammed V Stadium – the oldest in Morocco – was closed for renovation. Instead, I went to Mohammedia, a port founded nearby by the French in 1914, Chabab Mohammedia’s match against AS FAR of Rabat, and saw how a less well-preserved version of Casablanca might look, paint peeling off crumbling concrete buildings wherever I looked. Still, I was glad to have ignored advice and visited Casablanca, and I hope to return – especially now I know more of its histories, kept under the radars of most Western tourists.