Like many early Christian martyrs, Saint Sebastian (c. 255-288) was frequently portrayed by Renaissance painters – repeatedly by Andrea Mantegna and Guido Reni, but also by Botticelli, Albrecht Dürer, Titian, Anthony van Dyck and others. In 1977, Canadian critic Thomas Waugh wrote about ‘gay Renaissance painters who continually overdid it with St. Sebastian at the stake’ in an article on closeted Soviet filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein’s use of the saint in his ill-fated documentary “Que Viva Mexico” (1930-32). Waugh was writing a year after Derek Jarman’s debut feature film, “Sebastiane” (1976), co-directed with Paul Humfress and written in Latin, which drew out the queer subtext that could never have been made explicit in the 16th century – not even by Italian artist Giovanni Bazzi, nicknamed “Il Sodoma”, in his portrait of 1525.

Guido Reni: Saint Sebastian, 1615, Image via commons.wikmedia.org

A touchstone for queer portrayals

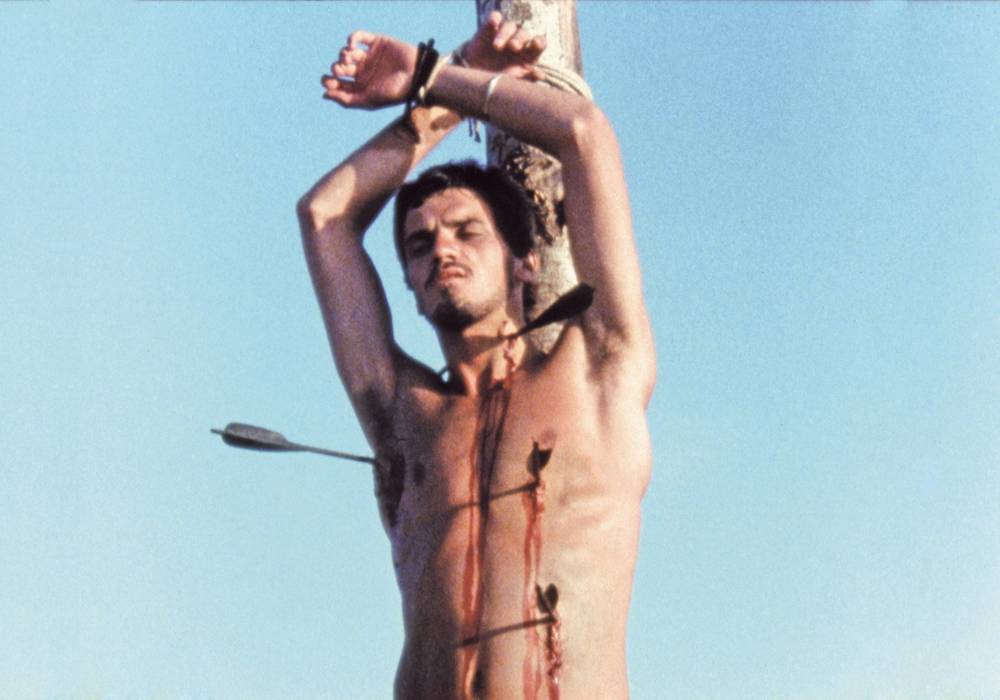

The outline of Sebastian’s story is covered in Humfress and Jarman’s film. According to ancient accounts, Sebastian was a captain of the Praetorian Guard under Roman Emperor Diocletian, who was unaware that Sebastian was a Christian, in the last wave of anti-Christian persecution. When Sebastian’s religion was discovered, he was sentenced to death by firing squad, and Sebastiane closes with the image, often reproduced in the Renaissance era, of Sebastian’s body riddled with arrows. What it does not show is that Sebastian reportedly survived, after being nursed by Saint Irene. He confronted Diocletian and was clubbed to death as a punishment.

Despite this omission, “Sebastiane” has become a touchstone for queer portrayals of the saint. It opens boldly, with a decadent queer performance in which men wearing exaggerated penises circle around a heavily made-up dancer (played by Lindsay Kemp), reminiscent of the orgies in improvised works by Sixties underground filmmakers Ron Rice and Jack Smith. Sebastian enters and kisses Diocletian, and then tries to intervene to stop one of the Emperor’s catamites being strangled by a Black guard. He is exiled to a remote coastal garrison and reduced in rank to private, before refusing to fight, preferring to devote himself to the Roman sun god Phoebus Apollo.

Derek Jarman and Paul Humfress: Sebastiane, 1976, Filmstill (c) Salzgeber , Image via spielfilm.de

Three deeply homoerotic narratives emerge: an ecstatic sexual affair between soldiers Adrian and Anthony, with long, lingering shots of them kissing in the glistening Mediterranean; soldier Justin’s friendship with, and unrequited love for his celibate, pacifist comrade; and commanding officer Severus’ obsession with Sebastian, whom he tortures and tries to assault, the implication being that Sebastian is executed for refusing his advances. The scenes of torture and the firing squad focus extensively on Sebastian’s body, with clear BDSM overtones in the way the saint seems to enjoy his suffering, made Jarman’s work so controversial on its release, but have cemented Sebastian’s appeal to subsequent artists across a variety of forms.

St. Sebastian in art from the 1960s onward

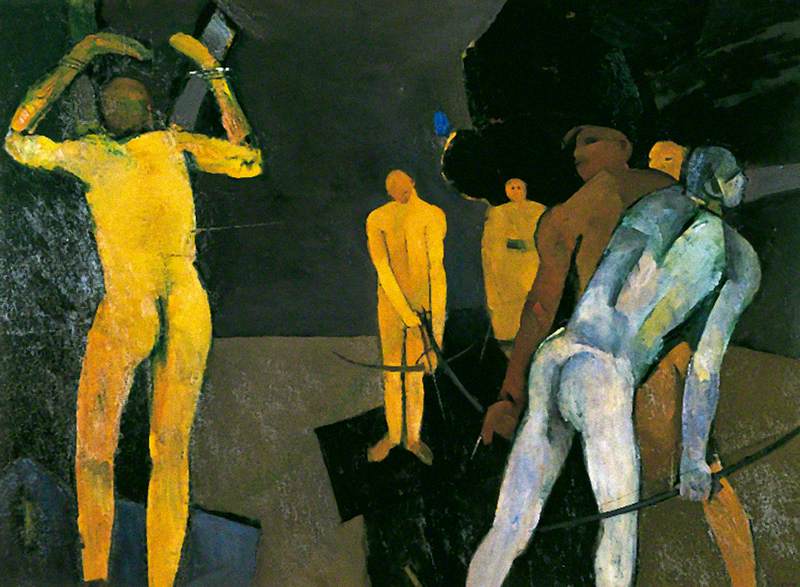

Jarman, however, was not the first gay British artist to present a sexualised portrayal of the subject. His friend and contemporary Keith Vaughan painted “The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian” in 1962, which shows several naked figures, with Sebastian chained to a cross and two men leaning suggestively across each other. Glauco Otavio Castilho Rodrigues’ “Saint Sebastian in June” (1985) depicts Sebastian, the patron saint of Rio de Janeiro, at the city carnival, with blood around his head, next to a crying woman with a rope tied around her wrist, behind a partying man wearing beach shorts in Brazil’s national colours. As with Jarman and Vaughan, Rodrigues challenges the viewer to consider the porous boundaries between pleasure and pain; in his national context, Rodrigues hints at the military dictatorship’s censorship of gay plays and publications, the homophobia present in left-wing opposition groups, and the struggle of the emerging Brazilian gay liberation movement to achieve visibility.

John Keith Vaughan: The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, 1962, Image via artuk.org

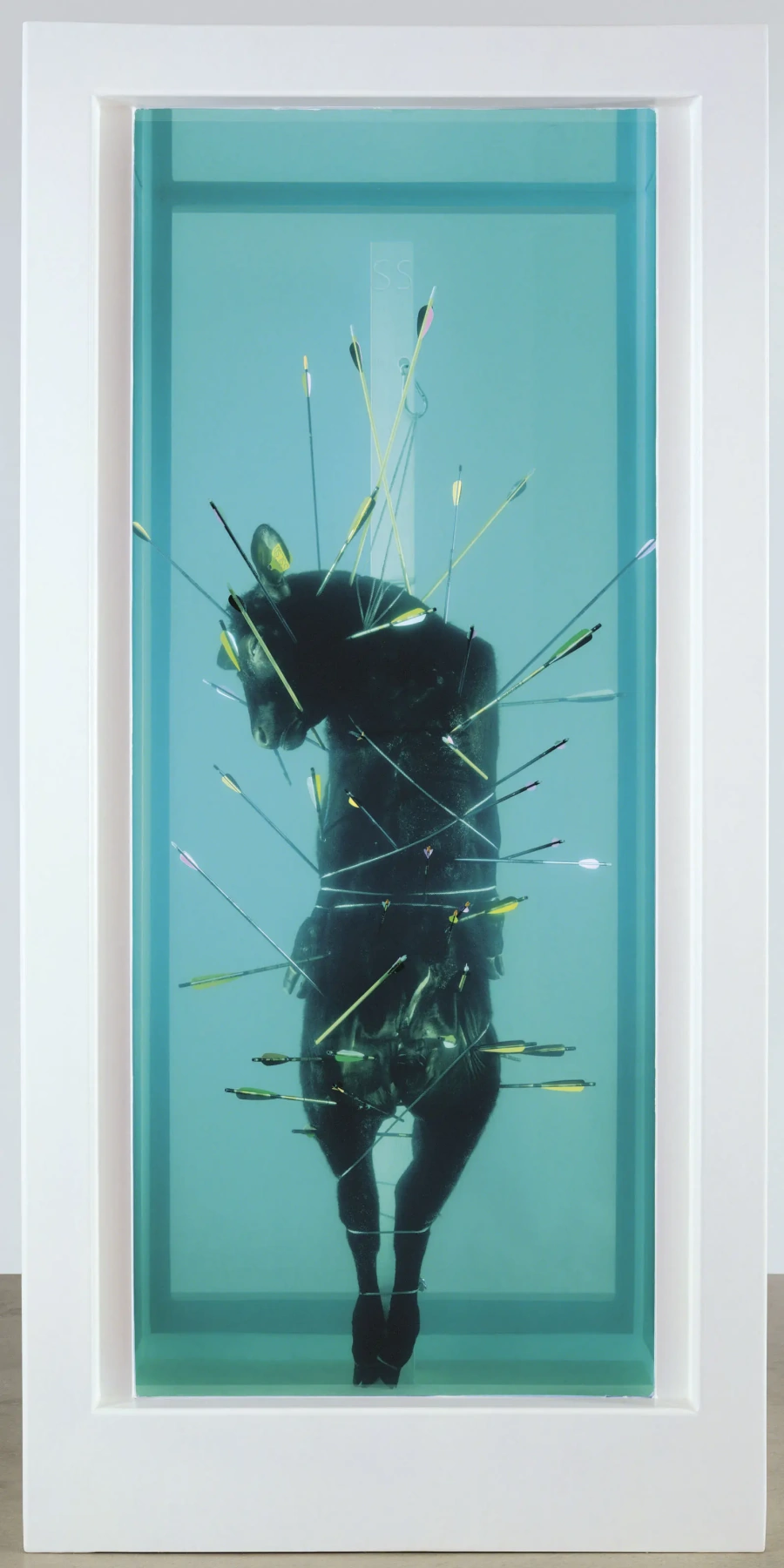

More recently, Louise Bourgeois and Damien Hirst both used abstracted images of Sebastian’s arrow-pierced body to portray pain in a visceral manner. Bourgeois’ “Saint Sebastienne” (1992) drew a headless female body to convey a physical and psychological state of siege; Hirst put a cow’s body, covered in arrows, in formaldehyde in “Saint Sebastian, Exquisite Pain” (2007).

Of more interest to a queer audience, perhaps, is Miles Greenberg’s “Étude pour Sébastien” (2023), an endurance performance in which the artist is painted, and pierced with real arrows. A film of this premiered at the Louvre in January, showing how Greenberg found a piercer via extreme US performance artist Ron Athey, and then performed in the gallery for five hours, replicating every pose he could remember from paintings, etchings and sculptures of Sebastian.

Damien Hirst: Saint Sebastian, Exquisite Pain, 2007, Image via arthive.com

It’s an incredibly intense work just to read about, let alone watch, or perform: Greenberg is at his most fascinating when he describes the adrenaline surges that the body produces on being pierced, essentially shutting down the senses to minimise the pain of (likely) death. This may account for the strangely delirious expressions on classical portraits of Sebastian, but the queer aspects of the story – its homosociality and sadomasochistic glee in cruel physical punishment – mean it will likely remain of interest to LGBT+ artists long after Greenberg’s extraordinary cataloguing of its historical portrayals.

Miles Greenberg, Étude pour Sébastien, 2023, Image via news.artnet.com