Marcel Duchamp’s (1887-1968) last great work was the subject of much discussion in the art scene. The artist had actually announced that he was finished with art and will dedicate his life to playing chess. He had, however, secretly been working for 20 years on his last coup – “Étant Donnés: 1. la chute d’eau 2. le gaz d’eclairage” (“Given: 1. The Waterfall 2. The Illuminating Gas”). Duchamp arranged for it to be only exhibited posthumously and accordingly, in 1969, “Étant Donnés” was conveyed to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where it has been on display ever since.

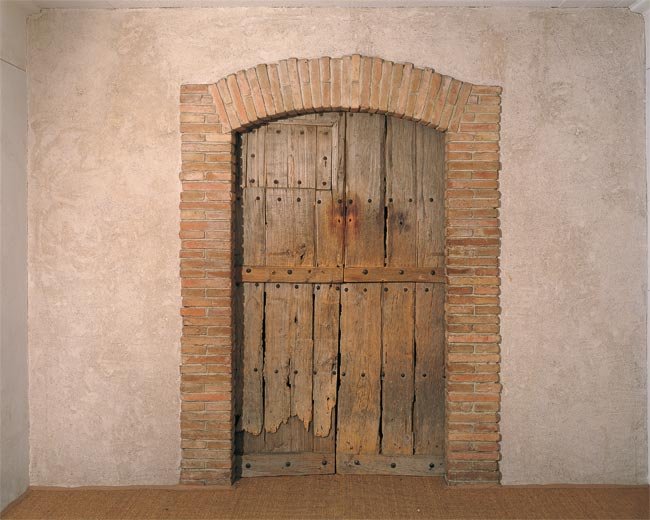

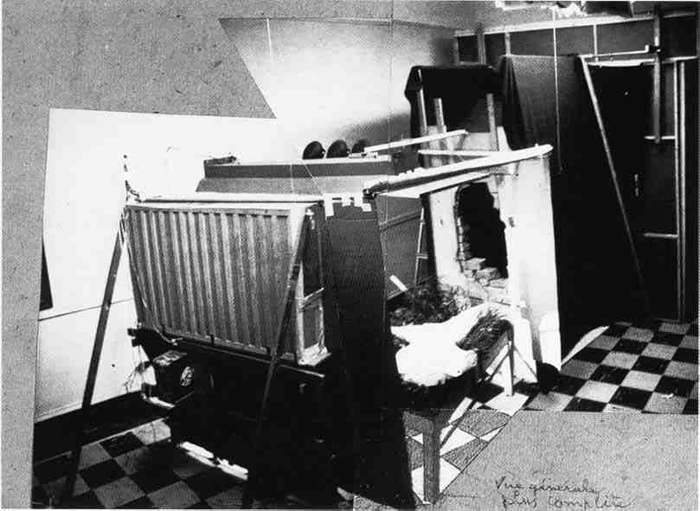

The mixed media assemblage consists of a weathered wooden door framed by bricks with a display case behind it. Two additional bars have been placed across the door, accentuating the fact that it cannot be opened under any circumstances. Only two little peepholes allow (visual) access to the scene behind the door. A trelliswork becomes apparent and this in turn reveals a landscape scene in the middle of which is a female nude. This seemingly headless body is lying, with outstretched arms and legs, on a bed of brushwood and leaves. Her left hand holds up a gas lamp which directs the viewer’s gaze out into a photographed landscape with a river and a flowing, illuminated waterfall in the background. The image in question is a manipulated photograph of Sur-le-Moulin in Switzerland.

Marcel Duchamp left exact instructions

Due to the difficult view, the process of looking is intensified and with the literally bricked-in perspective it becomes an active one. The work almost forces the voyeuristic gaze onto the open legs of the female nude and her pubic area. An intimidating proximity to what we are seeing is created. Marcel Duchamp developed his own art system, one in which the viewer’s reception is strictly controlled by the artist. For “Étant Donnés” he not only determined the point in time when the work would be published, he even left exact instructions about how it was to be exhibited. As well as stipulating the exhibition location and its venue, he composed a “Manual of Instructions for the Assembly of Étant Donnés”.

Marcel Duchamp Etant donnés 1946–66, Virtual Reproduction 2004

Courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art © Succession Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2008, Image via www.tate.org.uk

Marcel Duchamp, Interior view of Etant donnés: 1° la chute d'eau / 2° le gaz d'éclairage (Given: 1. The Waterfall /2. The Illuminating Gas), 1946-1966 © 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris, Image via www.researchgate.net

The handbook contains a collection of drawings, photographs, construction plans and notes relating to the work. The second and final version of this document, exclusively on the setup of the work, was published in 1966. It contains a 15-step set of instructions on how to (de)construct “Étant Donnés” as well as how to transport it. The manual acts as a set of instructions on how to approach the work, whilst simultaneously restricting the curator’s freedom.

Richard Jackson follows in Duchamp’s footsteps

Just under 40 years after the publication of “Étant Donnés”, Duchamp’s manual formed the starting point for one of Richard Jackson’s “Rooms”. The Californian artist is famous for his Expanded Painting, extending the boundaries of the canvas, replacing the stroke of his brush with machines. By so doing he is, to a certain extent, following in Duchamp’s footsteps as an anti-artist by subverting prevalent conventions and the process by which works of art are made. An important aspect in this context is the tension between what is on show and the viewer’s way of looking at it.

Marcel Duchamp, Étant Donnés: 1° la chute d‘eau, 2° le gaz d‘eclairage...(Konstruktion, Hauptansicht von der Rückseite), 1946-66, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Image via hugues-absil.com

For his work “The Maid’s Room” Jackson produced a set of instructions almost identical in format, contents, and title: “Manual of Instructions for ‘The Maid's Room’”. Jackson establishes a very clear relationship between Duchamp’s artistic production and his own: “I realized just how smart [Duchamp] was, the illusion, and the intelligent choices that he made. Anything that you can’t see through the hole doesn’t exist; which is pretty nice because you have to imagine it. What that piece does is what I’d like my paintings to do. They’re all finished, nobody saw how you did them, so they have to imagine what the process was.”

In “The Maid’s Room” Jackson transports “Étant Donnés” into a different time. All the elements remain in place, but he transposes them into a domestic environment. Duchamp’s forest scene has moved indoors, into the “maid’s room”. The female body made of shiny plastic appears distinctively artificial, the gas lamp has become the paint-spraying hose of a vacuum cleaner, the waterfall a running faucet and the photomontage some photo wallpaper. The woman is lying on a bed with splayed legs, a phallic symbol in her hand and only a chink in the window where the curtains that have been vaguely drawn closed allows the viewer to look at this highly private scene from the outside.

Anything that you can’t see through the hole doesn’t exist; [...] you have to imagine it.

Both Duchamp and Jackson abolish the conventional distinction between the work of art and real space by activating our perception. The viewers look at the three-dimensional representation of an alien scenery. With their works the artists force a voyeuristic and thus inevitably taboo view onto the displayed situations. Jackson’s “Room”, however, goes a little further by providing intimate insight into the private interior, which is otherwise protected from prying eyes. The gaze dominates the action of the viewer completely. Taking a look means participating, you inevitably become an accomplice of the intimate scene. The consequence? The responsibility of what is seen is transferred to the viewer. Not the others are the voyeurs, we are.