The end of the 19th century marked a new era in the medium of the newspaper. In 1883 the Hungarian-born publisher Joseph Pulitzer bought the then failing newspaper “New York World”. He transformed it into an unusually sensationalist paper and thus, within just a short time, it became one of the most influential newspapers in the country. A good decade later in 1895 the 16-year-old William Randolph Hearst entered the New York newspaper market by purchasing the “New York Morning Journal”. He came from a West-Coast family of multi-millionaires and had already taken over and revived the fortunes of the bankrupt “San Francisco Examiner”. Now in New York, he attempted to lure readers away from his competitors with even more spectacular headlines and a livelier layout. The tabloid press was born.

William Randolph Hearst, Image via boweryboyshistory.com

Hearst began a price war: He first sold his Sunday paper for 1 cent instead of the usual 3 to 5 cents, thus doubling its circulation overnight. His second move concerned the salaries of the most important employees: the cartoonists.

Chocolate figures and cigars

In 1896 Hearst’s offer of higher salaries enabled him to poach almost all of Pulitzer’s illustrators, including his right-hand man Richard F. Outcault. He had drawn the series “Hogan’s Alley” for Pulitzer’s newspaper “New York World”, the protagonist of which was a young boy with sticking-out ears and a yellow nightshirt. Outcault’s comic was so popular among readers that it boosted the paper’s circulation hugely. Merchandising items appeared in all conceivable forms – from stickers to chocolate figures to cigars – and the cartoon character became a sort of mascot for the “New York World”.

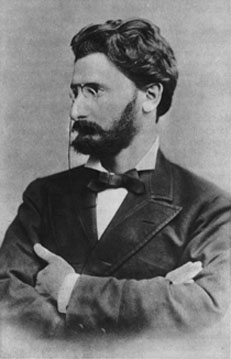

Joseph Pulitzer, Image via commons.wikimedia.org

For readers, the yellow nightshirt represented a new visual attraction. For a long time newspaper printers had tried in vain to print a yellow color that dried quickly and did not smudge. Yellow was the missing color required for four-color printing. Now the tabloid papers could finally print images in all colors (of the rainbow), and likewise print comics too. Whilst another German word for the tabloids is the “Regenbogenpresse”, or “rainbow press”, the American equivalent is “yellow press”. It is said that this term goes back to the yellow nightshirt of Outcault’s character.

The auteur comic

After Hearst had poached Outcault, the same character appeared in his newspaper, but this time under the series title “The Yellow Kid”, and it was this that led to the first copyright dispute in modern media history. A New York court decided that the rights to the character lie with the artist and that he could therefore take his characters with him when changing jobs. The publisher nevertheless retained the rights to the title of the series. Pulitzer therefore immediately instructed another illustrator to continue the series so that his newspaper would still contain a boy in a yellow nightshirt. The term “Yellow Kid journalism” was coined for the two warring newspapers with their similar comic figures.

The Yellow Kid, Image via commons.wikimedia.org

The competition among the publishers made the cartoonists wealthy, sought-after men and led to them enjoying huge amounts of freedom. Comics were still in their infancy; this was a relatively new medium and it was not yet clear which new trends would win out among readers. The illustrators were therefore able to do as they liked and were given a great deal of scope for creativity and experimentation. And the cartoonists not only drew their characters, but were also the authors of their stories. This would later change, but during the first few years of the medium one can truly say that, in an analogy with film, these were “auteur” comics.

Citizen Kane

The newspapers owned by Hearst and Pulitzer also – and here one might almost say unfortunately – dealt with political themes. With exaggerated and falsified articles, both editors attempted to lead the USA into a circulation-boosting war of liberation in the Spanish-Cuban conflict. In 1897 Hearst sent a reporter to Cuba, yet when he reported that everything was quiet Hearst is said to have furiously ordered him to stay, saying he would make sure there was a war one way or another. The newspapers succeeded in inflaming anti-Spanish sentiment. The violent events that followed brought about a change of heart in Pulitzer, however, and he subsequently dedicated himself to investigative journalism. Pulitzer is still renowned today for his journalism and as the name behind the journalism and media award known as the “Pulitzer Prize”. His competitor Hearst continued to build up his newspaper empire and became one of the richest men of his time; indeed he was the inspiration behind the title figure in Orson Welles’ classic movie “Citizen Kane”.