There is a photo depicting eleven men in suits. Most of them are sitting, some reclining, as if adopting a relaxed pose for the photo. All are wearing hats and all have beards. Only one, sitting on a sort of throne at the back left, is wearing a flowing reform dress. The image depicts the artists of the Viennese Secession. The man at the back left is Gustav Klimt. He had two objectives for his group of artists: to have their own exhibition building and their own magazine.

Members of the Vienna Secession, Image via secession.at

Even before the 20th century really got underway, there were groups that believed everything now had to be done innovatively, and this applied in art more than anywhere. The initial spark came from Great Britain with the so-called Arts and Crafts movement, which aimed to bring art and craftsmanship together to create Art for All. The idea of reforming life as a whole was an attractive one, and imitators on the Continent founded artists’ associations and colonies with the aim of trying out this new life.

Declaring war on bad taste

“Half-strike, half-refoundation”, wrote Ludwig Hevesi, as the artists surrounding Gustav Klimt broke away from Vienna’s Künstlerhaus. At the beginning of 1897 the City of Vienna granted the artists a building plot and unpaid workers erected the Secession building there according to plans by architect Joseph Maria Olbrich. When the building was inaugurated on November 18, 1898, two lines by Hevesi were displayed above the entrance: “Der Zeit ihre Kunst, der Kunst ihre Freiheit” (“To every age its art, to every art its freedom”). The author of books for young people, art critic and Nietzsche-devotee from Hungary became the most avid chronicler of the Viennese reform movement.

Gustav Klimt, “Fish Blood”, 1898, in the first edition of Ver Sacrum, Image wikipedia.org

The Secession also got its own magazine, “Ver Sacrum”. As early as the first edition there was an editorial stating “We want to declare war on sterile routine, on rigid Byzantinism, on all forms of bad taste.” This was aimed at academic painting, at the historicism in architecture and, most importantly, at the prevailing view of art. “Ver Sacrum” – meaning “Holy Spring” – was an organ for everyone who saw artistic life in this Danubian metropolis as too provincial and conservative. The title quotes a poem by the romantic poet Ludwig Uhland. Perhaps it was laid on a little thick, but the editors were aiming at precisely this romanticism of a new beginning. In contrast to other movements though, there was still no concept regarding the form this rejuvenation should take.

A race to catch up with modernism

One thing was clear, however. After all, the Secession came at a time of “sweeping things away”, as Hevesi wrote. The notion of rejuvenation was shaped nationally, almost nationalistically. What Paris, Berlin or Munich had done before now had to take place on the Danube too. The Secessionists called for a break with the historicism of the 19th century and a race to catch up with the modern metropolises.

Alfred Roller, titel Ver Sacrum, 1898 via Alfred Roller (1898), image via wikimedia.org

“There is a Vienna where things are really happening”, wrote Rainer Maria Rilke to the editorial team in 1900, when he no longer lived in Vienna. And “Ver Sacrum” reported on these events in the art world. Rilke would have gladly taken over as editor of “Ver Sacrum”, but the position was already occupied. Incidentally, Rilke wouldn’t have been paid for the position, as the editors worked for nothing. The first edition appeared in January 1898 without a patron behind it and without any support from the authorities.

Luxury nevertheless

It was not only the editors who worked for the publication for nothing; the artists also provided their prints free of charge. “We see no difference between ‘high art’ and ‘minor art’, between art for the rich and art for the poor. Art is common property”, were the words of the first edition. Despite that, “Ver Sacrum” remained a luxury publication, with articles on exhibitions as well as poetry and prose. The magazine could be found primarily in the more affluent salons of the capital where people were interested in modern art and where Gustav Klimt was a frequently seen guest.

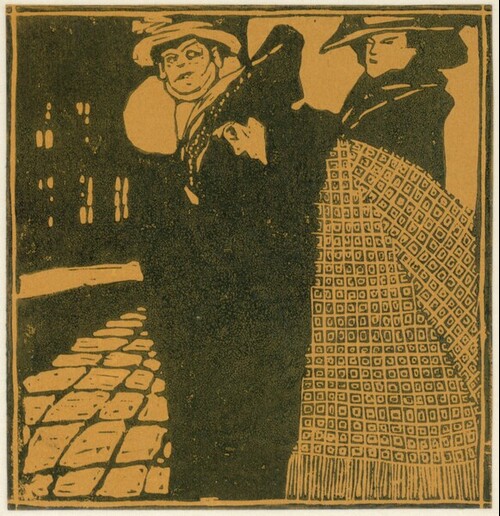

Koloman Moser, “Three Women on a Street Corner”, 1903, Image via albertina.at

It was in this magazine that the next stage of modernism revealed itself. The architect Adolf Loos wrote a polemic against the historical architectural eyesores of Vienna’s Ringstrasse. He subsequently argued with the coeditor Josef Hoffman regarding decoration. Loos would have liked to design a room in the Secession’s exhibition building – but Hoffmann wouldn’t let him. Then just a few years later, in 1908 to be precise, Loos would equate ornamentation with degeneration: “No ornament can any longer be made today by anyone who lives on our cultural level”.

Mockery and derision

The drive for ornamentation of the Viennese Jugendstil was soon to become a cliché, whilst “Secession style” became derogatory. In 1899 a student of Koloman Noser published a parody entitled “Quer Sacrum. Organ der Vereinigung bildender Künstler Irrlands”, which translates as “Skewed Spring. Journal of the Association of Fine Artists of Crazy-Land”. It adopted Ver Sacrum’s square format, as well as the typography, decoration and even the language the Secessionists used with their tendency towards metaphors of nature. Why this magazine was published no one really knows, according to the parody paper. But it apparently welcomes helpful submissions from readers.

Perhaps as a reaction to this, the artistic editors tidied up the layout of Ver Sacrum from 1900 onwards. The flowery patterns gave way to geometric ornamentation, which ran through the magazines like a common thread. From 1902 at the latest, “Ver Sacrum” became important for the rebirth of the woodcut. Koloman Moser, Carl Moll, Wilhelm Laage and Félix Valloton produced graphics especially for the magazine, and these no longer bore any resemblance to its flowery beginnings.

In 1903 “Ver Sacrum” disappeared quite unlike it had begun: very quietly. The magazine began to appear ever less regularly. Innovations went in other directions, and the springtime didn’t last long. Klimt and a few others left the Secession in 1905. Hevesi, the melancholy chronicler of the artistic springtime, took his own life five years later.

Hilde Exner, Tier-ABC, K-Katze, 1903, Image via johncoulthart.com