Reading the conversations between anthropologist Margaret Mead and political writer and poet James Baldwin, I am always drawn to the latter’s rigor and intellectual courage. The transcripts of their seven-and-a-half-hour 1970 conversations were published in 1971 under the title “A Rap on Race”, and among other concepts such as identity, history, responsibility, and guilt, race is indeed not just one link in the chain, race is the context.

The blurb of one of the editions states that Baldwin brings creativity and fire, while Mead is the voice of reason and scholarship. Evidently, the content and cover of a book can oscillate or, put another way, maybe even complement each other, in that the cover of the book with such a racializing characterization mirrors the analyses inside in one of many ways. Mead’s experiences as an anthropologist in the 1920s and 30s and her will to humanism nonetheless challenge and are challenged, as it were, by Baldwin’s pessimistic optimism, his analytical, cautious, and abiding mind.

“The ordinary American experience” becomes the topic of the conversation at a point where Mead describes how she experienced what race is: “You see, I had the reverse picture that most Americans have; because most white women picture a rapist as a black man. (...) But I had reversed it, and my picture of rape was of a black woman raped by a white man.” This “ordinary, everyday, simple experience” that Mead invokes is understandable to all who hear it. And yet it is elusive, in a double sense. Mead speaks of hegemony here, she explains why race matters socially, and hegemony, in this case the supremacy of a white majority, exists in the U.S. just as it does in Germany.

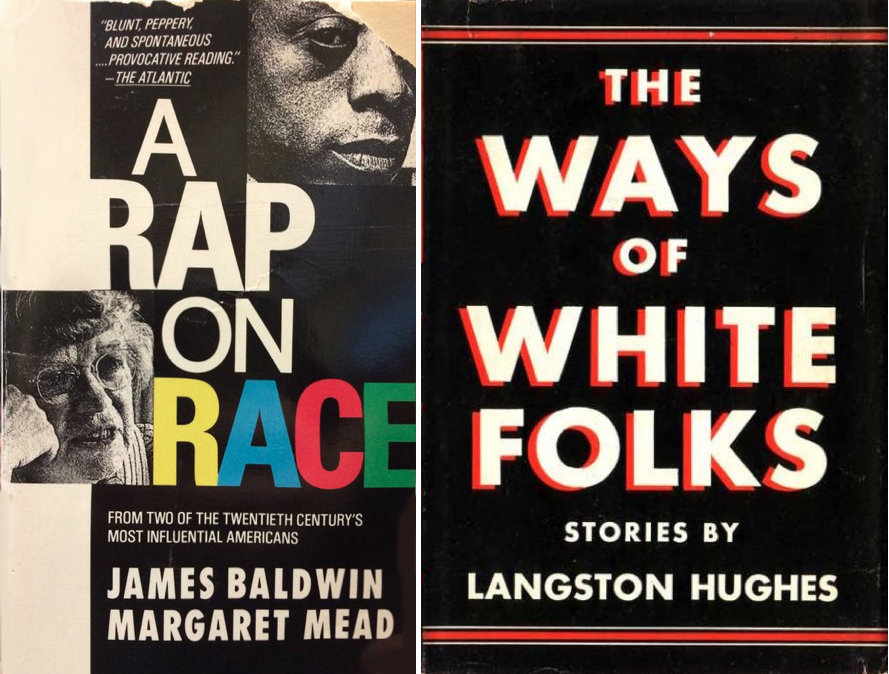

(Left) James Baldwin and Margaret Mead, A Rap On Race, book cover, 1970 / (Right) Langston Hughes, The Ways Of White Folks, book cover,1934, Image via contemporaryand.com

Mead describes a scenario that is abusive and criminal in which relationships, i.e. togetherness and thus the fabric of society, were very often imagined in the same way: White becomes the victim and Black the perpetrator. This “ordinary American experience” is coded in certain ways, with white not merely symbolizing innocence (like Christ’s white sacrificial lamb) but also purity and power, while black represents the sinister opposite (see Richard Dyer’s 1997 book “White: Essays on Race and Culture”). This is the ordinary American experience, described again and again in “A Rap on Race” with different motifs, models, and means.

This construction of race affects a specific and (socially, politically, geographically, economically, as well as culturally) situated history of the United States. The fact of racism, however, affects and infects more universally – some suffer from or die because of it, while others benefit and exploit it. Nearly 90 years ago, in 1934, U.S. poet and activist Langston Hughes remarkably depicted the differences in the experience of race in his book “The Ways of White Folks”. The book contains fourteen humorous, unbearably tragic, and instructive narratives of Black life and culture as lived in white U.S. America in the 1920s and early 1930s.

Langston Hughes, 1936, Foto: Carl Van Vechten, Image via WikiCommons

The portrayals of unusual but very real characters provide insight into the conditions of the times, while at the same time revealing human nature. Black life at the time was defined by racial segregation, enforced in the southern United States by the so-called Jim Crow laws, where lynchings were commonplace, and by a more subtle racism in the north. The racisms that one is presented with to comprehend in “The Ways of White Folks” somehow cannot be comprehended: they are complex, at times implicit, even playful, or only hinted at – in all their cruelty.

This fact of racism – which is based on and manifested through experience – is by no means uncontroversial, despite the simplicity of the formula: right-handed people are usually unaware of how much left-handed people are affected in everyday life only by this seemingly unimportant variation of a dominant hand, because the world was constructed for the former. White people are equally unaware of how often racialized people are disadvantaged in everyday life by structures of a society that prescribe and enforce a white perspective. It is through this perspective (which can only be thought of intersectionally to provide anything close to a complete picture of what a more just and inclusive society might look like) and within this description that power can be understood, power that has been embedded in whiteness for centuries. Or, as Stokely Carmichael once put it, “If a white man wants to lynch me, that's his problem. If he's got the power to lynch me, that's my problem.”

If a white man wants to lynch me, that’s his problem. If he’s got the power to lynch me, that’s my problem.

Stokely Carmichael, 1966, Image via WikiCommons

When something becomes structural, it tends to fade into the background and no longer be visible. Contrary to a widespread assumption, the levels of the individual and the structural are not mutually exclusive, they are dialectical. Racism is part of individual experience precisely because racism is so deeply embedded in the structures of society – in schools and universities, in prisons, in the media, in the legal system, in the penal system, and so on. Racism shapes all areas of the world today as it did 100 as well as fifty years ago, because racism is also a knowledge system that structures the social. Racism teaches us what we can know.

Racisms, moreover, are diverse and transform over time: the explicit Jim Crow racism in the U.S. discussed earlier, for example, morphed through a state of a claimed post-racial society of the 2010s then into a society with an overtly racist party with Donald Trump’s presidency – in a two-party system. In one era as well as the other, social responsibility of the legacy of enslavement, violence, and murder is evaded, in part because the structural dimension continues to be denied (see David Theo Goldberg’s book, 2015: “Are We All Post-Racial Yet?”). Thus, the struggle against a system becomes a struggle to prove that this system exists in the first place.

You know my fury about people is based precisely on the fact that I consider them to be responsible, moral creatures who so often do not act that way. But I am not surprised when they do.

If we look at who has the right to be a victim today – to return to Mead’s comment at the beginning – and who is doomed to remain a perpetrator, not much has changed. Police brutality in the U.S. as in Germany, images of the militarization of the EU, racist attacks, exclusions, statements, assumptions, and condemnations fill social media newsfeeds and other media. And it is a question of continuity and aggrieving perversity how flight, an escape from a globalized violent hegemony, is valorized within a racist logic. There is a perfidy in how people in this situation are represented and dealt with and the circumstances they escape from, and the images of their living and dead bodies, a dehumanization that only certain people are confronted with ubiquitously, are a grim reminder – not to say continuation – of the middle passage.

After the end of the unfathomable trial against the terror cell National Socialist Underground (NSU) in 2018, the racist terror attack in Hanau (2020), as well as the re-issued report (October 2021) on the death of Oury Jalloh, which establishes what should be an inescapable reality, that Oury Jalloh was set on fire in his prison cell, it becomes clearer than ever that we do not have the slightest idea how much Germany is riddled with racism, violent right-wingers and neo-Nazis. The events in Chemnitz of 2018 – marches by avowed Nazis who (can) proudly show the Hitler salute and prey on perceived non-Germans – are another glaring example of this.

Poster commemorating and remembering the people murdered in the racist attack in Hanau on February 19, 2020 © Amnesty International, Image via www.amnesty.de

Beate Zschäpe, the surviving member of the NSU terror group that killed nine migrants and a policewoman, was sentenced to life in prison. The trial, however, may go down in history as a demonstration of how strongly the police and the state are structured by deep institutional racism, from the original designation of the case as the “Döner murders” to several well-known cases of disappearance and destruction of files and an ignorance of dissenting perpetrator profiles to the treatment of the victims’ surviving dependents.

Germany is painfully struggling to deny racism. But it has taken root in all areas of society. In sports, in industry, in advertising, in the arts and culture. The police do not shy away from illegal racial profiling. The reconstruction of the Humboldt Forum in Berlin has taken place despite widespread protests; the hosting of colonial artifacts by German museums in general has only recently been questioned, and very cautiously at that. The term “Rasse” – which is more akin in meaning to the English “breed” – is still considered by many to be a valid way of referring to or talking about people of different origins.

Berliner Schloss, Humboldt Forum, Berlin, Deutschland, September 2020, Image via WikiCommons

Significantly, “Rasse” is used in the German constitution; a discourse around it has likewise recently unfolded, and the term was part of the justification for the German Empire’s extermination campaign in what is now Namibia between 1904 and 1908. This first genocide of the twentieth century was not acknowledged in 2004 when the first apology was issued by the then development aid minister, but the German government distanced itself from it. The lawsuit for reparations, initiated in 2001, was settled in May of this year, after which the Foreign Minister Heiko Maaß announced for the first time, 113 years after the events, that from now on Germany would speak of a genocide.

In the Berlin district of Wedding, many streets bear the names of those colonial generals who were responsible for acts of colonial violence. After years of struggle by activists, the Central Council of the African Community, the Initiative Black People in Germany and other organizations, the renaming of the Berlin subway station “Mohrenstraße” to “Anton-Wilhelm-Amo-Straße” was announced in May 2020. However, these are and remain all memorials to the city’s entanglement with its and Germany’s colonial history. This almost seemingly arbitrary list could go on for a long time, but what it tells is this: Our whole way of life carries complicity, a culture that naturalizes the privileges that come with whiteness – and these privileges affect many more people than we might initially think. They affect all of us in one way or another.

The ways of white folks, I mean some white folks, is too much for me.