“O my body, make of me always a man who questions!” is one of the most memorable quotes from Franz Fanon’s “Black Skin, White Masks”. Released in 1952 the book has become a seminal text in postcolonial theory for its interrogation of the colonized self and its unpacking of the complex ways in which identity, particularly Blackness is constructed and produced in the context of colonization.

The main premise of the book is that the process in which Black men internalize myths of Blackness invented by colonial society leads to them damaging their psyches. Consequently, this produces an inferiority complex that leads Black subjects to appropriate and imitate the culture of the colonizer, especially if they are upwardly mobile and educated (like Fanon himself).

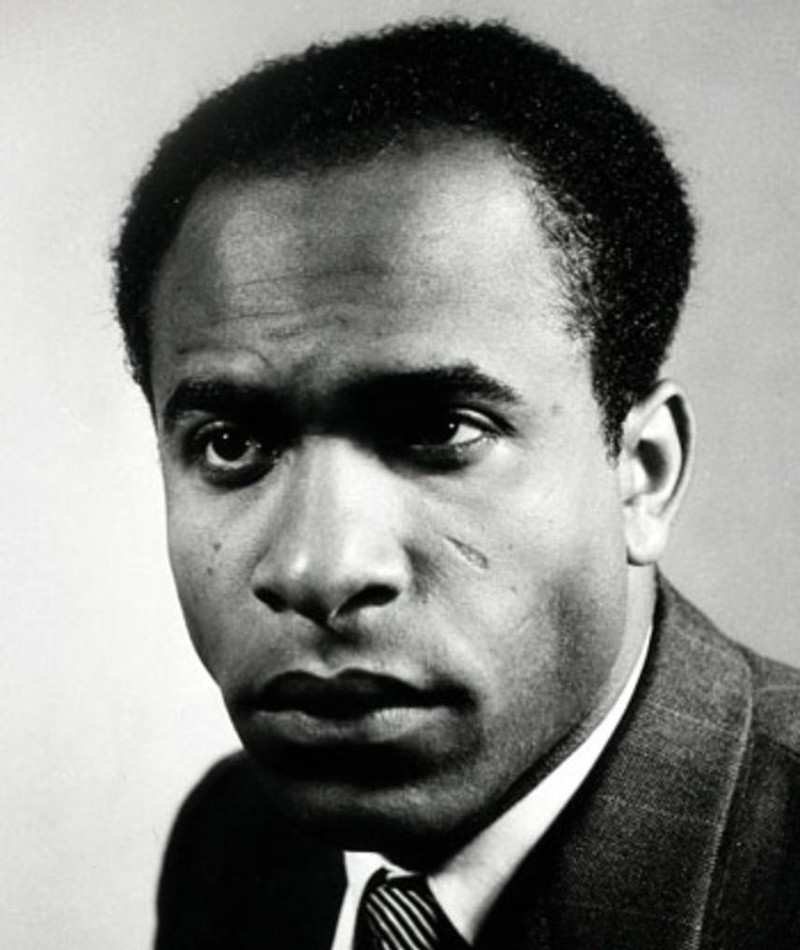

Frantz Fanon is considered groundbreaking, but also controversial

The book and the author are largely influential but also controversial. To this day they still draw praise for the issues it identifies and criticism for its generalisation of feminist and queer issues. Yet so instrumental and ground-breaking are the main ideas of the book that it went on to influence whole generations of Black queer artists who not only used Fanon’s ideas but transgressed them to rethink the nature of Black homosexuality, masculinity and femininity.

Frantz Fanon, Image via mubi.com

Fanon described colonialism and its impact as being largely made up of visual experiences. This gaze, according to thim, appropriates and depersonalises its subjects while ignoring their way of seeing. In turn queer theorists, especially in film, have appropriated these terms and applied them to gender. Rotimi Fani-Kayodé was one of those artists and he even made art that referenced directly “Black Skin, White Masks”.

“On three counts I am an outsider”, the Nigerian artist said in relation to his postcolonial position in the world. “In matters of sexuality; in terms of geographical and cultural dislocation; and in the sense of not having become the sort of respectably married professional my parents might have hoped for.” Born in Lagos in 1955 and from a wealthy Yoruba family, he moved to England as a refugee from the Nigerian civil war at the age of 12. After his studies in fine arts and economics in the USA he returned to London where he worked as an artist until he passed in 1989 from conditions related to HIV.

On three counts I am an outsider

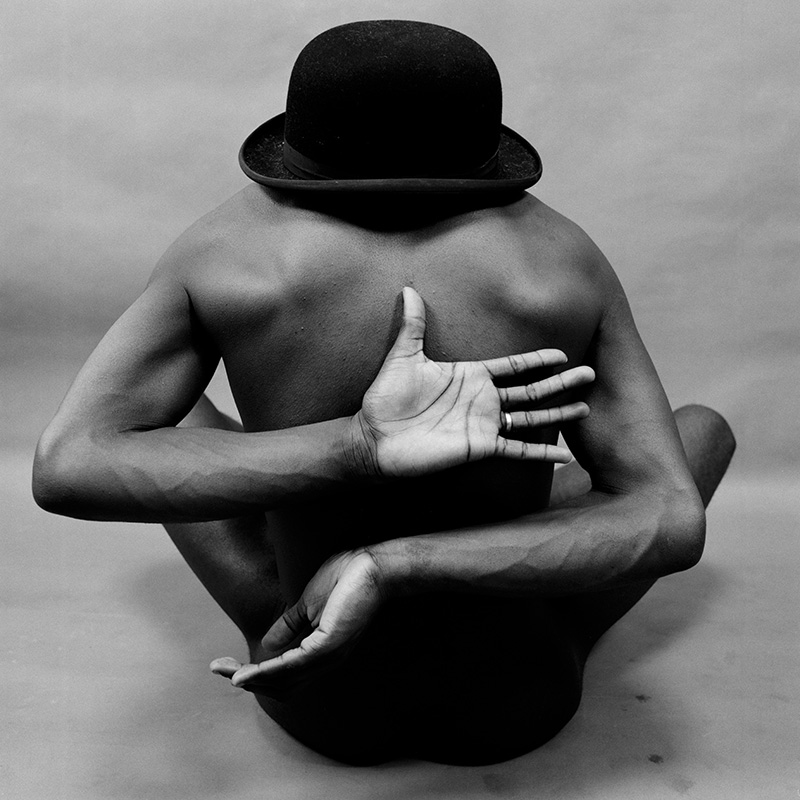

Rotimi Fani-Kayode, City Gent, 1988, Image via autograph.org.uk

Fani-Kayodé combined sexual and cultural differences to deal with Black homosexuality head on. In “The Golden Phallus” (1989) the artist shows a naked young athletic Black man posing on a platform wearing a white beak mask looking into the camera. His penis is gold-plated and kept up with a white string. So, on the one hand Fani-Kayodé explores Black sexuality in relation to a Black subject being gazed upon by the world.

Fani-Kayodé explores Black sexuality in his art

But on the other, he challenges Fanon’s suggestion that male homosexuality only exists for the enjoyment of the white man, by having the subject’s penis hung by a string showing that he is not sexually readily available. Yet the multi-layered work further challenges straight male assumptions of homosexuality with its ambiguous quality, full of both deliberate connotations and various possibilities for interpretation.

View of “Rotimi Fani-Kayode,” 2019. Top: Maternal Milk, ca. 1986. Bottom, from left: Nothing to Lose XII (Bodies of Experience), 1989; The Golden Phallus, 1989, Image via www.artforum.com

Also in London, in 1995 a pivotal group exhibition in London marked a moment considering the importance of Franz Fanon and ways in which his writings intertwined with artistic practices, gender and race. Entitled “Mirage: Enigmas Of Race, Difference & Desire” and curated by David A Bailey at the ICA, the show included queer artist such as Isaac Julien and Lyle Ashton Harris, among others.

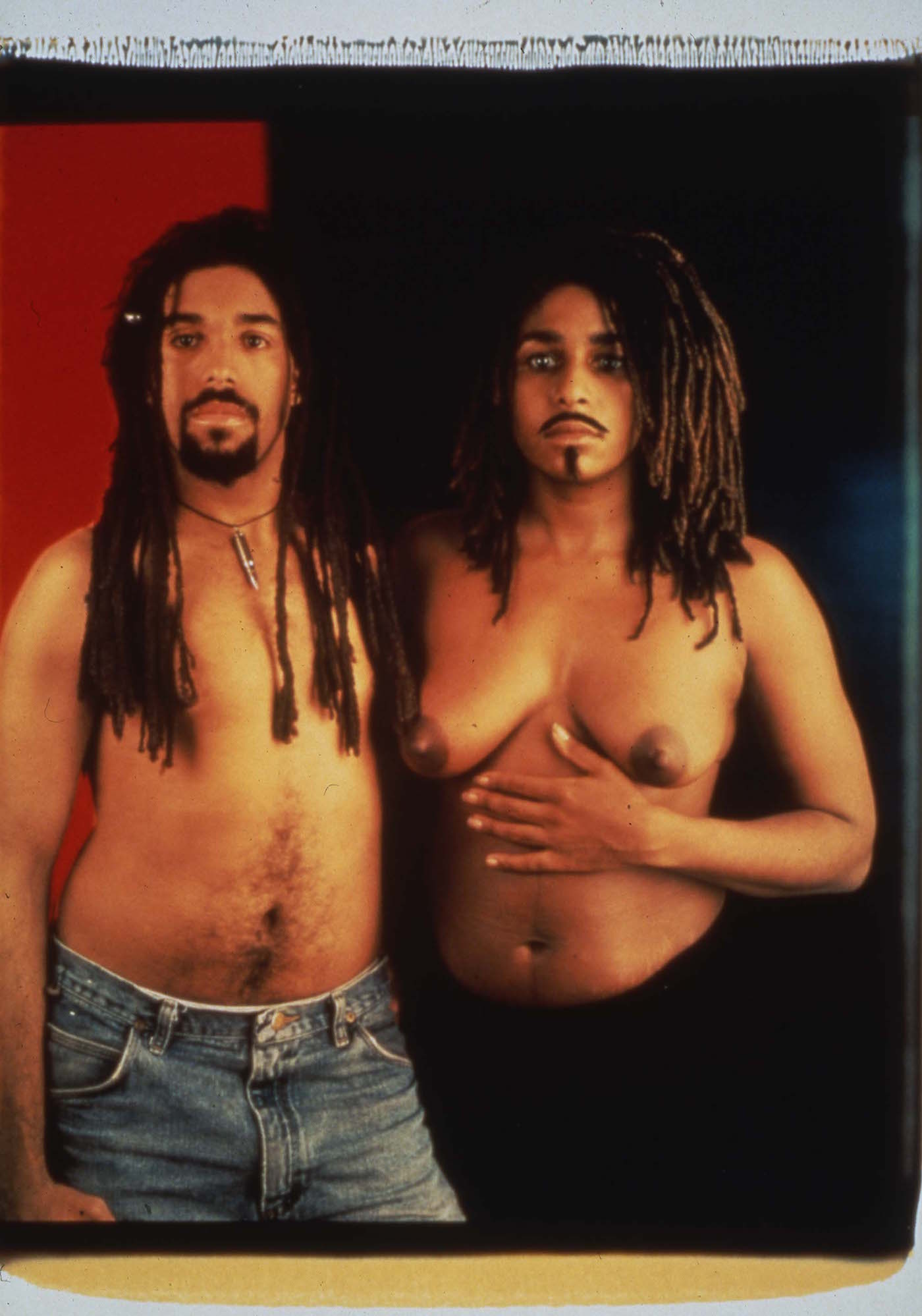

His work depicts queer Black people in intimate domestic settings

The North American artist Lyle Ashton Harris showed a series of photographs exploring family bonds and homoeroticism through portraiture. Dread and Renee (1994) portrays a topless man and woman (judging from the breasts) embracing. Both have dreadlocks and realistic facial hair. The picture challenges, if not downright negates, what Fanon suggested about homosexuality only existing as a victim of the slave mentality by showing two Black people in an intimate and homely setting. Simultaneously it agrees with Fanon’s premise that ultimately, we as Black subjects have to self-reflect and self-analyse.

Lyle Ashton Harris, Dread and Renee, 1994. Courtesy the artist, Image via contemporaryand.com

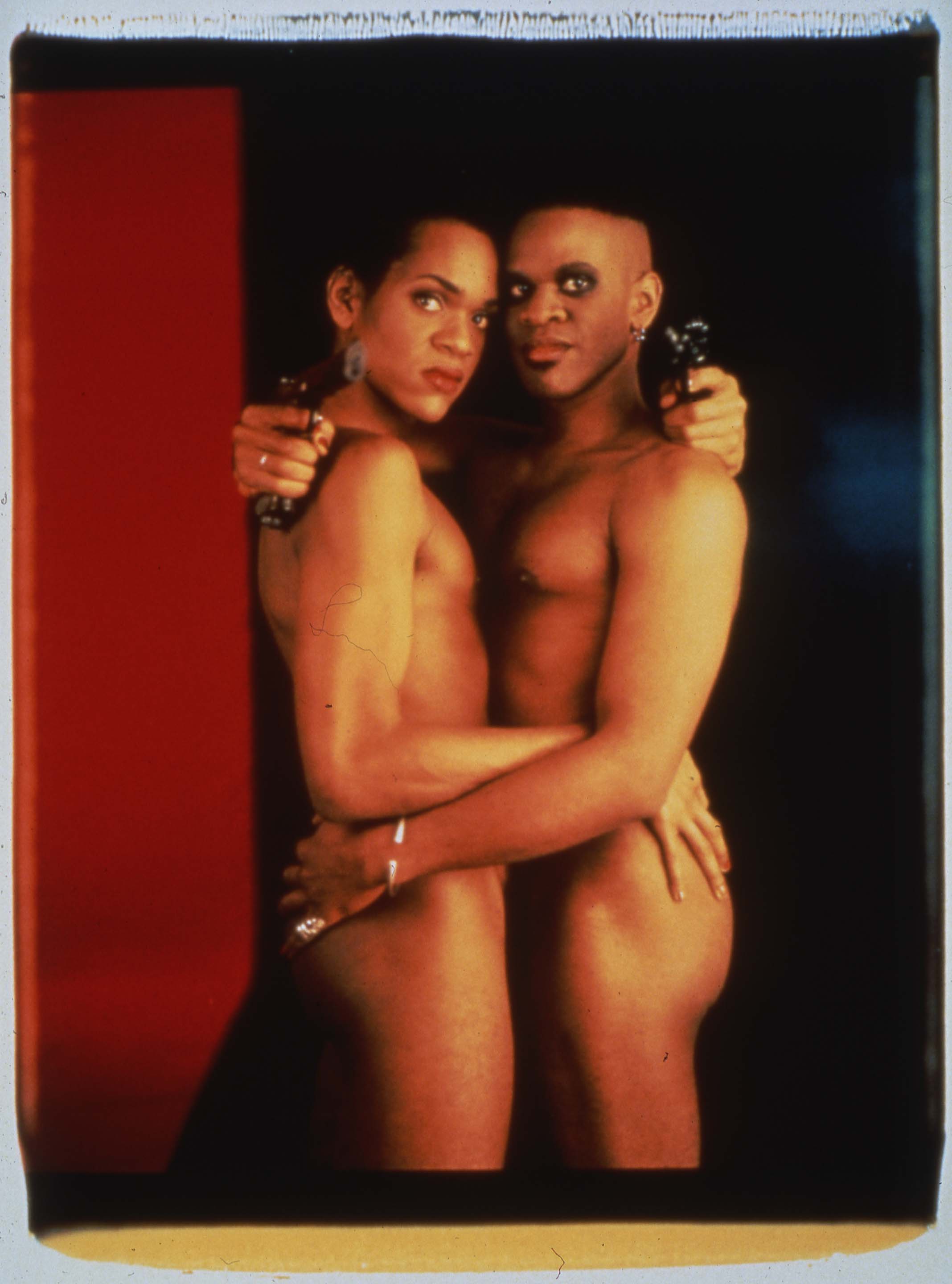

Harris’ “Brotherhood #3” takes it one step further by showing two naked Black men with makeup on embracing. Not only are they looking at the camera but they’re also pointing two guns at it, clearly affirming their awareness of being under constant attack and needing to defend themselves but also reinforcing their agency and refusing to be victims.

In Zanele Muholi’s solo show “Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness” in 2017, the South African artist proposed another fierce study of gender, race, ethnicity and sexuality. This time around, the photographer who’s become known for her visual activism documenting queer communities of South Africa, turned the camera on herself. This she argued was needed in order to reconnect to herself again. Though she does it with powerful self-reflection and always giving the camera an intense fixed look. In addition to the self-assured stare, the artist also darkens her skin highlighting that she knows that she is not only a queer woman but a Black African woman too and that that’s how the world sees her or how she wants the world to see her.

LYLE ASHTON HARRIS + T. A. HARRIS, BROTHERHOOD #3, 1994, Image via renaissancesociety.org

In Alain Polo’s “Serié blanche” (2016), the Congolese artist plays with similar codes but in reverse by bleaching the image of Black naked bodies so that they become ethnically ambiguous. This way the artist tries to free the photographed body from a Western gaze that exoticizes it by controlling the image (and his body) himself. Also confronting this very difference that Fanon so emphasised is Eric Gyamfi. In “Just Like Us” (2016) Ghanaian artist documented the daily lives of the heterogeneous queer community in Ghana forcing us to question what is actually different. This approach challenges the heteronormative gaze and the artist takes it one step further by juxtaposing it with offline and online abusive comments, complicating Fanon’s maximums by emphasising the importance of the Black community sees itself regardless of the white gaze.

Fanon set the impetus to question everything

What’s so remarkable about Franz Fanon’s “Black Skin, White Masks” is that despite being short sighted in terms of gender it still remains an enduring tool for Black queer artists. In 1997 Isaac Julien even made a film about it. “Frantz Fanon: Black Skin White Mask” is film essay that criticises Fanon as much as it praises him. And perhaps that embodies the biggest gift that Fanon has given Black queer artists – the impetus to question everything, to regard no one as a hero and most importantly to question and place ourselves in relation to the world around us.

Eric Gyamfi, Untitled, from Just Like Us Series, 2016. Courtesy the artist, Image via contemporaryand.com