Alice Waters, chef and co-founder of the famous Californian slow food restaurant Chez Panisse, summed up the close connection between art and cooking: “...they are both reactive and creative, imitating and adapting to each other.” So is there a connection between what happens in the studios of artists and what happens in their kitchens? Are there references to their work and personality? Are artists particularly creative when it comes to the everyday act of cooking? With the help of anecdotes and photos about their kitchens and eating habits, we provide insights into the culinary worlds of well-known artists.

Rirkrit Tiravanija’s “spirit animal” is the fruit fly. This not-entirely-serious conclusion was reached by the Thai artist one evening with friends, when the conversation took a rather comical-esoteric turn. The fact that Tiravanija identifies with this somewhat inconspicuous creature, of all things, might appear rather strange at first glance – after all, for more than two decades now he has been one of the discernible greats of the international art scene, the very opposite of the literal “fly on the wall”.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Do we Dream under the Same Sky, installation view, Art Basel 2015, Image via myartguides.com

Rirkrit Tiravanija, installation view, Image via tiffobenii.wordpress.com

Born in Argentina in 1961, Tiravanija lived a virtually nomadic childhood and youth as the son of a Thai diplomat, moving between South America, Thailand, Ethiopia and Canada. Even today, he is always on the go, living between Chiang Mai, Berlin and New York, and regularly flies around the globe upon the invitation of various institutions. Those seeking a gravitational center in his life will likely settle on what was the kitchen of his grandmother Somrit Suwannabol in Bangkok, where Tiravanija spent a lot of time as a child. Suwannabol was well-known throughout Thailand as a nutritional expert and chef, running a restaurant in the garden of her house, founding a catering firm, and even appearing on Thai TV. It was among the pots and pans of her homely restaurant that Tiravanija developed not only an interest in food, but also in the social components of cooking and hosting.

His grandmother’s handwritten recipes accompanied him all the way to Toronto where he studied in the early 1980s and spent every Sunday cooking up a huge pot of curry to share with friends and acquaintances. After spending time in Chicago, he ended up in New York, where he likewise prepared meals in great style according to Suwannabol’s instructions, albeit this time as part of a group exhibition at the Paula Allen Gallery. In the middle of the exhibition space, he made pad thai, distributing it free of charge to visitors, which many mistook to be a catering service. Through the interaction with the food and the exchange among those involved, the audience – knowingly or unknowingly – became a central part of the artwork. The action broke with the expectations and conventions of the artworld and marked an important milestone in the varied and multidisciplinary career of Tiravanija, whose works aim to create situations that turn passive onlookers into active participants, blurring the dividing line between art and life.

Behind the supposedly simple cooking activity, there also lie complex issues, for example those of his own cultural identity – as a Thai person who was educated in a system molded by Western values – or of the “authenticity” of dishes like pad thai, which was introduced by Prime Minister Plaek Phibunsongkhram at the end of the 1930s to encourage consumption of protein-rich rice noodles and bolster Thai national pride. Only those who look very closely will discover the manifold levels of meaning that hide behind Tiravanija’s actions: The use of an electric wok from the brand “West Bend” in “pad thai (1990)” is a reference to the Martha Rosler’s video performance “The East is Red, The West is Bending” (1977), in which the artist reflects on cultural appropriation, and it stands as an example of the usurpation of Eastern cultural goods by the West and their transformation into consumer goods.

Throughout his career as a culinary artist, Tiravanija has repeatedly deviated from the classic recipes of Thai cuisine and integrated important elements of food culture from his immediate surroundings. In Stockholm’s Moderna Museet, he cooked up Swedish meatballs with green curry paste, while in Hamburg’s Kunstverein he prepared “Flädlesuppe” – a “typical German dish”, which nevertheless appears strangely out of place in Hamburg and which, through the addition of cayenne pepper, confounded the audience’s expectations all the more. Turning traditional dishes on their heads through the unrestrained mixing of ingredients of different origins is something Tiravanija considers a credible alternative to the omnipresent “fusion cuisine”, which is often nothing more than a reproduction of cliches about different countries’ typical eating habits.

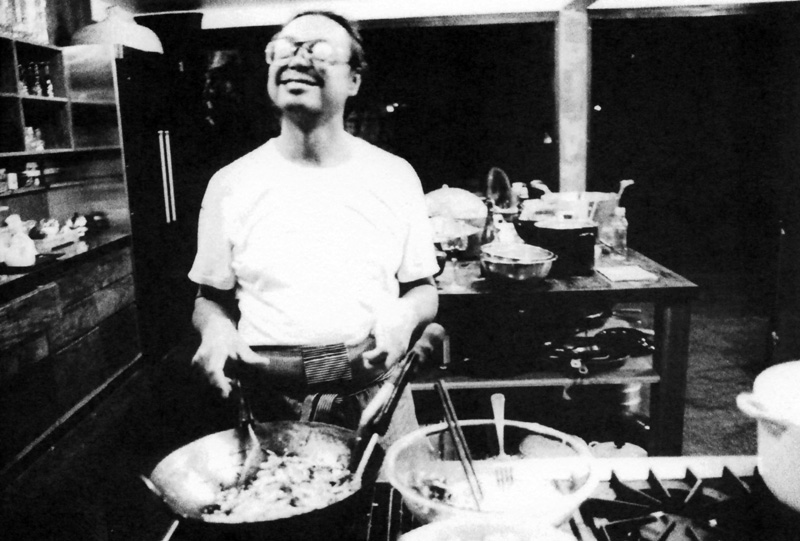

RIRKRIT TIRAVANIJA by © ANTOINETTE AURELL, Image via www.we-find-wildness.com

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Installation view: “untitled 1990 (pad thai)” at Paula Allen Gallery in New York (1990), Image via www.surfacemag.com

In his house in Chiang Mai in the north of Thailand, Tiravanija likewise skillfully combines Western and Eastern cultural influences: Here, elements of traditional Thai architecture meet the ideas of European Modernism in the style of the architect Mies van der Rohe. In the spacious kitchen-diner, it becomes clear that the artist’s ideas about cooking and eating as a “social adhesive” are likewise firmly anchored in his everyday life. At the dining table alone, there is space for fourteen people to sit comfortably, and Tiravanija describes his whole house as one big sofa on which friends, family members, colleagues and students regularly come together to eat and exchange ideas.

While at the start of his career Tiravanija was always the one at the wok, now he often cooks only at openings; for his exhibition “Who’s afraid of red, yellow, and green” (2019) at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, he handed over responsibility entirely to a local Thai restaurant. Indeed, he also outsourced the execution of drawings depicting various protest movements, which graced the walls in Washington, to art students, too. And thus he explains his identification with the fruit fly: Tiravanija actually has no interest in being at the center of his actions; he would rather the exhibition visitors took center-stage. As a fly, he would be able to remain entirely inconspicuous on the wall and observe in peace the specific dynamic his ideas develop as soon as the audience takes ownership of them. And once the last morsel of curry has been spooned up, he would simply fly away.