Martha Rosler thinks about food a lot. This may hardly seem worth mentioning, as we actually all do, be it out of passion or necessity. Yet while our thoughts revolve around cooking for ourselves or having food delivered, the content of our fridge or the shortest route to the next ice cream parlor, the New York-based concept artist, activist and cultural theorist sees the kitchen as the central arena of socio-political debates. For Rosler, cooking represents far more than the mere preparation of food: She sees in it a political act that reveals a great deal about social role models, class differences and cultural capital.

When in 1975 the artist donned an apron to stand in the kitchen for her now-iconic performance video “Semiotics of the Kitchen”, it soon became clear that she did not intend to prepare a meal. Borrowing aesthetically from the era’s typical TV cooking shows, with a dead-pan facial expression Rosler presented a series of cooking utensils in alphabetical order with energetic hand movements. In this way, she embodied the antithesis to popular TV-chef Julia Child. “Apron”, “Beater”, “Colander”, Rosler exclaims while defiantly looking straight into the camera. In the role of the frustrated housewife suffocated by the corset of domestic duties, the artist is at most boiling with rage.

Julia Child, Image via thecinemaholic.com

The dry wit with which Rosler delivers her thoroughly serious social critique is to be encountered in many of the artworks she has produced since the 1960s, as diverse as they are in both content and form. Martha Rosler glides effortlessly back and forth between film, collage, photography and text, and her thematic range is also remarkable: It extends from the Vietnam War to gentrification processes, media images of the body, the mechanisms of the art market, consumer society, and many other big topics that she dissects with precision and reassembles in her works.

Between Gastronomy and Imperialism

The self-proclaimed “Socialist feminist” places a special focus on female role models and stereotypes, among other things as connected to the culture of the kitchen and the food industry.

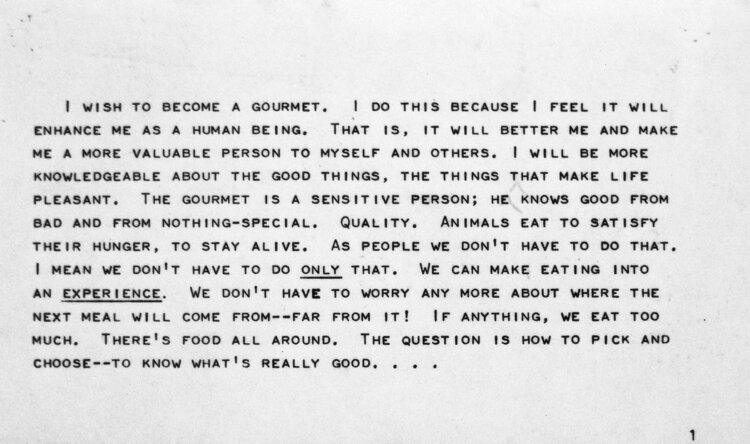

For her work “A Budding Gourmet”, created in 1974 and published in the shape of a serial postcard novel, Martha Rosler dons the role of the housewife once more. Told from the main character’s point of view, she recounts her efforts to become a gourmet in order to raise her family’s social status. She is convinced it would make her a better human being to learn the tricks of French haute cuisine and to serve up “exotic” Brazilian dishes for her guests, inspired by her last trip abroad. The protagonist’s naïve-sounding statements point to a complex discourse about class, culinary neocolonialism, and the close connection between what we eat and what we think we are.

Martha Rosler: A Budding Gourmet: Food novel 1, 1974, Image via martharosler.net

Martha Rosler, “A Gourmet Experience” (1974), installation with banquet table, video, slide projections, audio, books, cookbook readings, and prints of the food novel A Budding gourmet (artwork © Martha Rosler), Image via hyperallergic.com

Rosler shows the extent to which gastronomy and imperialism are entangled in “The East is Red, The West is Bending” (1977) . In a cheerful voice she here “insanely literally” reads out on camera the brochure of an electric wok of the West Bend brand, which promises ambitious home cooks that they, too, can become experts in “exotic cuisine” with the help of its product. The kitchen appliance is here said to combine the “authenticity of an Asian wok” with Western technology (a power connection and a Teflon coating), Rosler explains in the style of a teleshopping show, reproduces colonialist thought patterns in passing.

Incidentally, Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija referenced Rosler’s video piece in his 1990 performance “Pad Thai” by cooking the eponymous dish in a wok of the West Bend brand.

Martha Rosler, The East is Red, The West is Bending, 1977, Image via arxiu.mostrafilmsdones.cat

Our everyday life is permeated by political ideology, even if this is not always readily apparent at first glance – and this holds true for the ostensibly easily digestible genre of cookery books. Rosler’s extensive library of 7,800 volumes also includes several dozens of these, including “The Settlement Cookbook: The Way to a Man’s Heart” (1901); “Larousse Gastronomique” (1938); “The Complete Book of Oriental Cooking” (1965) and “Foods of the World” (1968-71), a 27-volume cookbook series issued by Time Life Books. However, Rosler did not buy these books in order to advance her cooking skills, but as research material. In the early 1970s, she wrote: “The Art of Cooking” a fictitious dialogue between Julia Child and then-restaurant critic for the New York Times Craig Claiborne. Made up for the most part of quotes lifted from cookbooks of different eras, Rosler recombined these to turn them into a brilliant, sarcastic discussion relating to the hierarchies of taste and value in art and gastronomy. Conceived in an era when the marketing of richly illustrated cookbooks whetted the appetite of an aspiring middle class for new culinary experiences that didn’t require them to leave the comfort zone of their own homes, “The Art of Cooking” has lost none of its relevance to this day.

Craig Claiborne, Image via e-flux.com

Julia Child, Image via e-flux.com

Nothing is known of Martha Rosler’s own tastes for food, which is hardly surprising given that the artist is emphatically opposed to her work as an artist being associated with her private life. She finds that aspect entirely boring. And yet she regularly documents and publishes her meals in a very particular context: For the series “Air Fare” Rosler, who commissioned by museums and galleries has been flying around the world for half a century, photographs the food she is served high up in the sky.

Martha Rosler, Air Fare, ongoing, Image via martharosler.net

Her growing success over the years has brought an upgrade in the airplane cabin and correspondingly also on the tray, yet the images don’t exactly make you work up an appetite, but much rather stimulate your thoughts. In classic Rosler fashion, the artist manages with the help of everyday observation to point to overarching contexts and bring food for thought on the politics of food production, the precariousness of service personnel, social inequality and cultural norms to the (fold-out) table.