What would the French inventor Joseph-Marie Jacquard have said if somebody had explained to him that his ground-breaking development of the mechanical loom of 1805 would not only make a crucial contribution to the Industrial Revolution but would also have a not inconsiderable influence on computerization in the 20th and 21st centuries? For his Jacquard loom, he was the first to make the punch card control system that was still in its infancy practicable for use: The loom could thus automatically spin whatever conceivable pattern was mapped out on the punch card. This binary system of the punch card would later be applied to the digital world and was used for computer controls as late as the 1980s. Jacquard was thus the first to separate software from hardware, as the social historian Hans G. Helms puts it.

It seemed fantastic to me to be able to build individually with geometric thread elements point by point, line by line

At the end of the 1950s the now painter, graphic designer, video artist, and former Städel Professor Thomas Bayrle was working on precisely such a Jacquard loom after his training as a pattern drawer and weaver: “I wanted to become a pattern drawer and to learn how to make punch cards in order to be able to ‘program’ patterns. […] It seemed fantastic to me to be able to build individually with geometric thread elements point by point, line by line,” he explained in an interview with Kunstforum Magazine in 1995. Indeed, Bayrle’s works, created from the late 1960s onwards through programming and building from the smallest individual elements, might also be described as weavings that only take their shape from the joining of threads and fabrics.

The faces become superstars

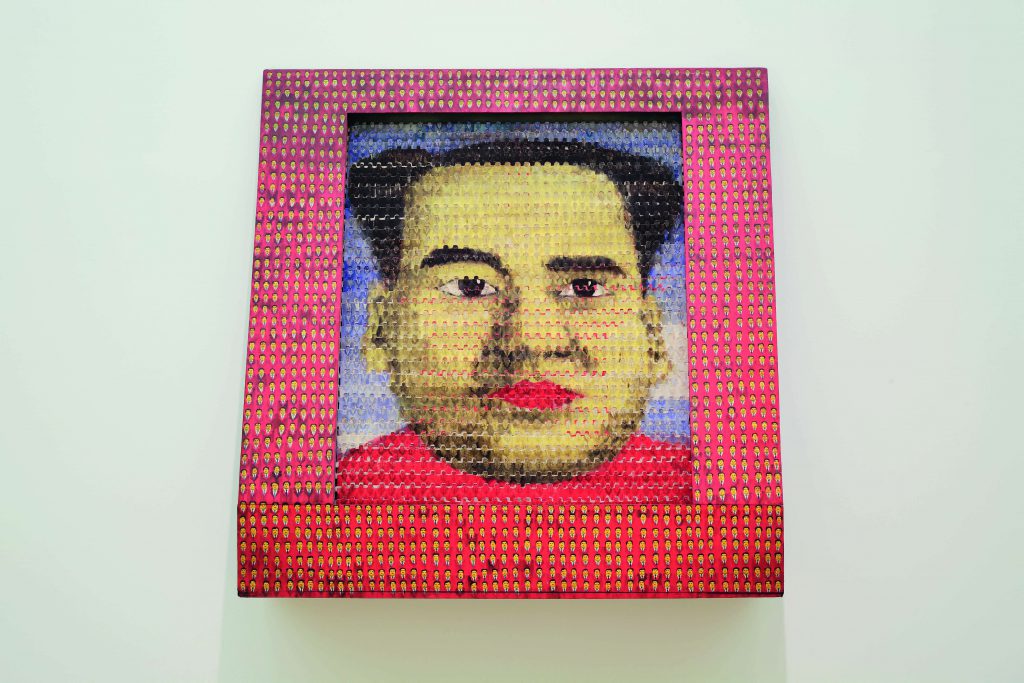

Countless individual parts, robbed of their individuality, merge into a new whole, a kind of collective. Hence, in the mechanical object “Mao” from 1996, hundreds of small figures form what Bayrle terms a new “superform”: the portrait of the then leader of the Chinese Communist Party, Mao Zedong. Thomas Bayrle worked this way, always starting from the graphic, with lithographs, etchings, silkscreens, and various photographic techniques before dedicating himself in a similar way to video technology from 1980 onwards.

Thomas Bayrle, Mao, 1966, Nationalgalerie, Photo: Axel Schneider / © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2019, Image via freunde-der-nationalgalerie.de

November’s edition of Double Feature will include four video works from the 1990s: “Gummibaum”, “Sunbeam”, “Superstars” (each 1993-4), and “Dolly Animation” (1998). In “Superstars” he takes short film or TV loops and uses computer-assisted technology to map the faces of those he had previously shown in the loops, juxtaposed ten thousand times. They thus, to a certain extent, become the “superstars” of the title – larger-than-life, unreal beings. “Dolly Animation” applies a similar technology: Here, however, the mapped sheep consists of individual images of a priest kneeling before an altar and images of the evidently eponymous cloned sheep Dolly.

Enlarged pores, mapped images

In both works, the camera circles the swirling, teeming images in constant zooms: Again and again, Bayrle enlarges the individual pores of the mapped images, which briefly reveal the individual loops before the virtual overall image once again becomes visible. In “Gummibaum”, meanwhile, the artist projects footage of children playing onto the leaves of a plant as if they were wandering aphids. This plant, for its part, appears again in “Sunbeam”, but here it is a parking lot scene that plays out in a continuously repeating loop. The same principle applies on an audio level: The loud slamming of doors from the sequences shown is repeated continuously and, in “Sunbeam” especially, develops a rhythmic urgency in its overlapping that threatens to burst again and again.

The individual is the thread, the mass is the fabric. Particles form parts and parts form superparts in the sentence

The very specific sequence coupled with the constant repetition of the myriads of images gives rise to new “superforms”, or rather new “super-images”. The individual meaning of the loops seems to merge directly into them, and yet Bayrle never quite loses sight of the original images. “The individual is the thread, the mass is the fabric. Particles form parts and parts form superparts in the sentence,” or so the artist himself pointedly concludes.

As additional films, Thomas Bayrle has chosen two works by the Austrian jack-of-all-trades Peter Kubelka. Among his achievements as a filmmaker, Kubelka laid the foundations for the structural films of the 1960s and 70s with his metric films from the 1950s. Together with Peter Kronlecher, he founded the Austrian Film Museum in 1964, was co-founder of the Anthology Film Archive in New York, and – like Thomas Bayrle – was professor and later rector at the Städelschule in Frankfurt, where he became the first person to teach cooking at an art school as part of his “class for film and cooking as an art genre”.

With “Adebar“ (1957) and “Schwechater“ (1958), two works from his metric film series are to be featured. Both works last not much longer than a minute and were originally conceived as advertising films: one for the Adebar pub, the other for the Schwechater brewery.

The starting point here are strictly metrical guidelines: In “Adebar” the music divides the image, showing dancing couples both in negative and positive, into meticulously structured sequences, which in turn repeat themselves serially. In “Schwechater”, individual image frames are broken down into different groups, in the course of which, for example, the color values slowly change, while the image shows people celebrating and drinking beer. It’s not hard to guess that at the time the commissioning clients were not keen to use the artistically experimental works as advertising films. The Schwechater brewery even prohibited Kubelka from showing the work at the World Exhibition in Brussels, and the artist was therefore forced to steal a copy of the film from the copying workshop.

A reduction of cinema to its essence

Frames, lighting, montage – in “Adebar” and “Schwechater” Kubelka reduces cinema to its essence, which he then projects onto the big screen. It’s not hard to recognize the link to Thomas Bayrle’s way of working, which in the large “superforms” returns again and again to the smallest unit that functions like an atom, holding together the larger format as a whole, which could of course not exist in the first place without the individual elements.

Peter Kubelka, Schwechater, 1958, Image via sixpackfilm.com