A gloomy room, a tense atmosphere: two men, both intensely focused, surrounded by countless utensils that seem somehow warlike. One of them takes a crowbar in his hand, the other reaches for a kind of wooden cudgel. It doesn’t take long before fists start to fly: Eventually, one of them jumps over a cupboard into a dark corner, while the other flails around wildly.

In the room, grotesque chaos has ensued; on the floor lie broken wooden boards, food residues are thrown around, and a meat hook in the middle of the room evokes unpleasant fears. Then suddenly we hear a voice from off-screen: “Cut! We’re out of sync!”, and the two men erupt into laughter. Thus, it is revealed that the scene shows not an excess of violence between two adversaries, but rather an insight into a day at work for two Foley artists, as sound-makers are known within the film industry. The clip comes from Terry Burke’s short documentary film “Track Stars: The Unseen Heroes of Movie Sound” from 1979.

What do “Planet Earth”, “Avengers” and Fassbinder’s “Martha” have in common?

So: What do entirely different film productions such as the major BBC documentary series “Planet Earth II”, Hollywood blockbusters à la “Avengers: Endgame” or, for example, a Rainer Werner Fassbinder film like “Martha” from the 1970s have in common? All of them relied, to a not inconsiderable extent, on Foley artists. It is they who give the films the realism audiences expect, which allows viewers to immerse themselves in the events of the narrative.

Foley-Artists, Image via infocusfilmschool.com

The need to enhance the immersive experience of a film using effects and sounds comes from the age of silent movies. Even back in the 1910s, certain film orchestras had sound machines that could replicate up to 50 different effects. Conventional motion-picture theaters with their silent film pianists or organists would use these simple honks or jingles to enhance certain effects – sometimes to the audience’s displeasure. Hence the complaints of a critic in the “Film-Kurier” in 1920, for example: “[…] as soon as a car appeared, which happened rather often, we heard a toot-toot in the room. This really was overkill; it sounded barbaric and ruined the atmosphere completely.”

Later, in 1927, Warner Bros. released “The Jazz Singers”, and thus a film containing not only synchronized music passages and singing, but also occasional sequences of dialogue –a novelty in this combination. The film very soon became the first successful sound film and therefore helped tremendously in propelling the shift from silent movies to so-called “talkies”.

This really was overkill; it sounded barbaric and ruined the atmosphere completely.

It was precisely around this point in time that Universal was working on filming of the Broadway audience favorite “Showboat”, a major silent film production. After completion of the film, the studio was thrown into a panic by the success of “The Jazz Singers”, since the bosses feared – quite rightly – that audiences would now expect a sound version of a musical production. The release of “Showboat” was therefore abruptly delayed and various scenes were re-shot, making the film with its sound sequences 30 minutes longer. For the dubbing, the studio brought on board Jack Donovan Foley, who had already worked as a sound-maker for radio.

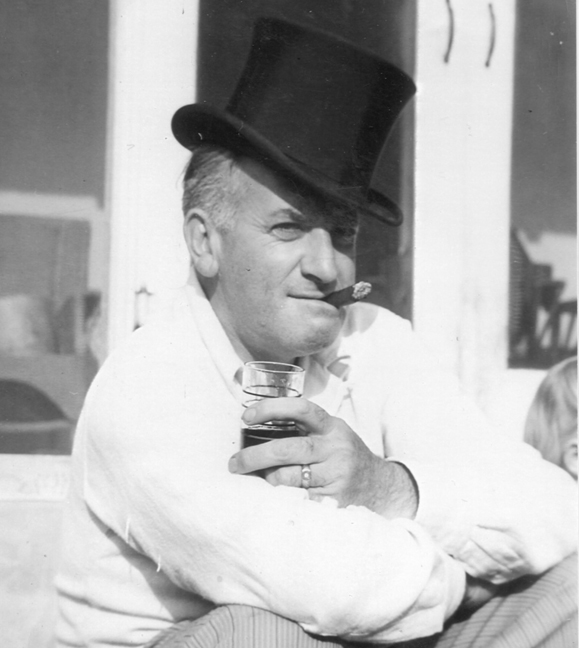

Jack Foley, Image via irishamerica.com

Since technical limitations meant it was virtually impossible to record situational or other atmospheric sounds (what they called “atmo”) during filming, Foley came up with a groundbreaking idea. The sound for the film scenes was to be recorded live in the studio synchronously with the screening of the film, instead of the usual process whereby scenes were simply set to effects produced in advance.

A Foley artist’s studio is rather like an older child’s play den

Foley expected this to create much greater realism and the success of the method was to prove him right. Soon, all major production studios were using the technique to provide sound for their films. While the recording techniques may have improved continuously since then, the work of Foley artists has remained fundamentally the same: These days, the sound technology on the film set serves mainly to record dialogue in such a way that there is as little interference as possible, meaning that as little dialogue as possible has to be synchronized subsequently. To this end, shoe soles are insulated, for example, and other peripheral sounds eradicated entirely to get the clearest possible recording.

Foley Art, Image via www.berklee.edu

One of the main tasks of Foley artists remains recording footsteps and the sounds of movement in sync with the action of the film. Other peripheral sounds are divided up between the different sound departments. While noises from machines tend to be dubbed using synthesizers or existing stock sounds, it remains both less time-consuming and more straightforward to commission a Foley artist with providing the sounds of doors closing, rain, inhalation of cigarette smoke, crashing waves, or animal noises, for example.

A Foley artist’s studio is therefore rather like an older child’s play den: an entire arsenal of shoes, various sample surfaces, doors, cupboards, all manner of odds and ends that can produce sound, small wash basins and various eating utensils for dubbing splatter noises (if someone’s skull is smashed in a film, for example, a watermelon can be used to make the right sound in a Foley artist’s studio).

Foley Art Requisiten, Image via columbian.com

Sound penetrates the center of our perception in a more direct and unfiltered way than the image, which we have learned to call into question. Without giving much thought to it, most people undoubtedly assume that in wildlife documentaries like “Planet Earth”, for example, they are hearing the actual flapping of the hummingbird, the roar of a lion, the galloping of antelope or the sound of a shark swimming, when it is actually the work of a sound artist. The creativity of the Foley artist and the entire sound department thus also has an influence on the fundamental acoustic perception of the viewer.

It’s probably widely known that pistol shots and punches sound considerably duller in real life than they do on film – and yet: If the actual sound were used it would probably be dismissed as “unrealistic”. Hence, Foley artists are becoming the modern magicians of sensory perception: Using maize starch in a bag they can conjure up the crunching of snow on a winter walk, with coconut shells they evoke the sound of a galloping horse, and from a mere cup they can suddenly mimic the croaking of a frog. Terry Burke calls Foley artists the “unseen heroes” of film, and it’s true that they bring sound films to life.

Jack Foley was never mentioned for his work in any credit line

Viewers tend to be more inclined to forgive a poor image than poor sound, which can automatically lead to a production being perceived as amateur or indeed “not authentic”. Incidentally though, these pioneering efforts towards sound film have never been given appropriate recognition: Jack Foley worked as a sound artist for Universal for more than 33 years, yet never was his name included in any credits. His fame is limited primarily to those working in the film industry, with sound-makers known by his name the world over, and in 1997 Foley was posthumously awarded the Motion Picture Sound Editor Award.

Foley Art, Image via www.cssd.ac.uk

Foley Art, Image via wordpress.com