“Tell me what you want me to be, how you want me to be. I can be that – I can be anything,” Mabel Longhetti promises her husband Nick in John Cassavetes’ “A Woman Under the Influence.” Mabel Longhetti is later admitted to a locked psychiatric unit, because her husband cannot decide whether he would rather have a conforming wife who is able to function in society or one who is “somewhat unusual,” as he puts it.

Evidently Mabel herself has no say in the matter and ends up being the one who is caught up between the expectations and various roles she is assigned as wife, lover, friend, mother and daughter. Similarly, the multilingual off-screen voices in Eli Cortiñas’ (born 1976) video work “Quella che cammina” (2014) seem to represent the collective internalization of other people’s expectations and role assignments: “We women never have the confidence to do anything, we behave like proletarians,” we hear at the very beginning. “I know that I have to achieve something in order to be a worthwhile person. I know I mustn’t fail, and I must not be fat, either,” it goes on.

The mother’s interference

“Quella che cammina” was produced during an artist residency at Villa Massima in Rome. The work is a collage comprising shots and scenes from Carlo Lizzani’s contribution to the collective Italian work “L’amore in città” from 1953. In his film contribution “Amore che si paga” Lizzani introduced his viewers to an older prostitute, whose colleagues only know her by the name of “Quella che cammina” [“The one who walks”]. Cortiñas has Spanish, Italian, and French women talk about expectations and experiences they have had with finding themselves, love, sex, society – until finally the artist’s mother interrupts and intervenes in her daughter’s work on a meta level, which dictates the image, categorizes it artistically, then ultimately reveals that she herself is only following the script.

Alongside the original shots from “Amore che si paga” we see interior and exterior shots, which include sculptures and smaller installations by Cortiñas. The camera always remains very close to the filmed object, never giving a wider shot to reveal the context, like the off-screen voices, whose speech the viewer has to make sense of him or herself.

Broken china

It is not unusual for the artist to resort to found footage in photo or film collages. In her prize-winning work “Dial M for Mother” (2009), for example, she combined excerpts from various John Cassavetes films with recordings from telephone conversations with her own mother, and in “Perfidia” (2012) she used film sequences from Buñuel’s “Le charme discret de la bourgeoisie” in a different context. There are further references in “Quella che cammina”: the film poster from “Leave her to heaven,” a melodramatic film noir by John M. Stahl from the 1950s, and repeatedly photographs of Hollywood actresses, whose heads always remain in the dark. At the end we hear the mother again: “My daughter is an artist,” she says, and “Originally, this film was to be called “Everything I never had the courage to do.” Afterwards, we see broken china.

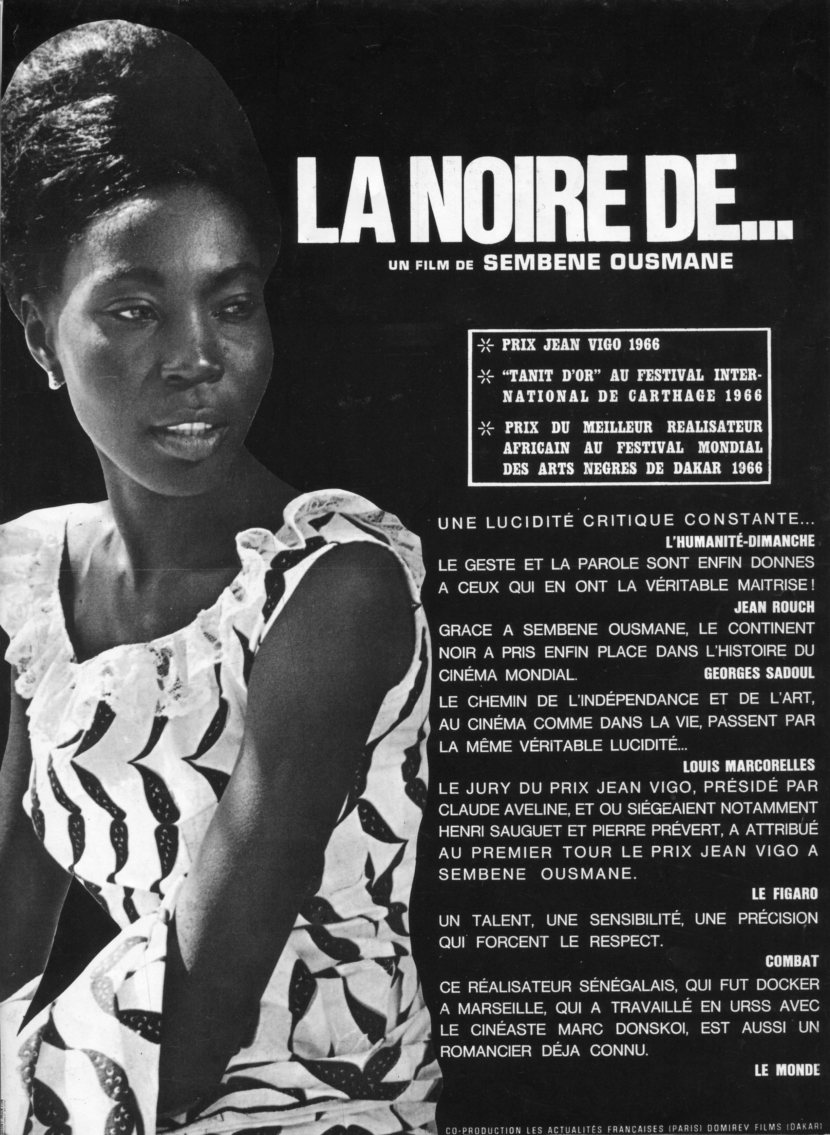

“La Noire de…” (1966) by Ousmane Sembène, which Cortiñas chose as her favorite film, is considered to be one of the first African films to attract international attention. Just under an hour long, it is the first feature film by director and author Sembène, who had previously made two short films reminiscent of Italian neorealism. The film is loosely based on a newspaper article and revolves around a Senegalese woman named Diouana (Mbissine Thérèse Diop), who is originally hired by a rich French couple in Dakar as an au pair, before following them to Antibes under the assumption that she will be looking after their children there.

Like a slave

Instead, she is constantly harassed by the couple, whose attitude towards her becomes increasingly authoritarian and foul tempered. She is given only menial housework to do, while the couple’s children are not even present. Having looked forward to a life in France Diouana sees her hopes dashed. She is rarely allowed out, receives no pay and is more or less treated like a slave. Then, at a dinner the couple give for friends, Diouana is introduced like some new, smart accessory and a guest kisses her without her consent because: “I’ve never kissed a negress before!” The situation becomes so much worse after the arrival of the children that Diouana finally commits suicide.

In his film Sembène addresses the rampant racism of post-colonial societies, which see and treat the people of former colonies more like objects than people. The couple repeatedly talk about Diouana in her presence as if she were a small child or an animal.

The ego cannot come to rest

Interestingly, it is almost always the wife who displays her power over the employee and oppresses him or her. “La Noire de …” tells a bitter story of assigned roles and simultaneously the inability to have any clear sort of idea about who one is. The fact that assigned roles may sometimes be adopted in part is something we also see in “Quella che cammina”: The persistent off-screen voices seem to nag away at the Self like the Freudian superego and id, and the Self has no idea how to deal with all these demands and expectations. Consequently the titular subject, who is always walking, might perhaps be seen as the ego itself, which can never come to rest.

La Noire de..., Image via fullunemploymentcinema