If one is to believe current media coverage and survey results, social democracy has been in pretty poor shape in Europe for some time now. Yet reality is often not quite as simple as things appear at first glance: While some can no longer make out what the classic Social Democratic parties even stand for these days and seek to overtake them on the left, others identify Social Democratic policies throughout the entire spectrum of party politics and thus report that now even conservative governments are acting – and ruling – in a Social-Democratic way. This has admittedly not yet asked what social democracy means in the first place; all that remains evident is the fact that even in 2016 the ideology of democratic socialism has been neither spelled out down to the last details nor wiped out.

Holger Wüst, The Social Democratic Way of Thinking. An Image as a Film, 2012, Image via holgerwuest.tumblr.com

The piece by Holger Wüst (born 1970), “The Social Democratic Way of Thinking. An Image as a Film” from the year 2012, bears the all-important words and the chain of associations that go with them in its very title. The 45-minute work is actually a film about an image: Throughout the entire time, the camera lingers, gliding thoughtfully across a photo collage produced by Wüst, getting lost in small details, changing the shot size and delving ever deeper until it zooms out and opens up the view to the full panorama. In the melancholy absence of color, the black-and-white images are reminiscent of Michelangelo Antonioni’s films of the early 1960s: We see Brutalist buildings, the critics of which like to label this architectural style, with its cold appearance, as one expression of totalitarianism.

A dreary and fascinating world

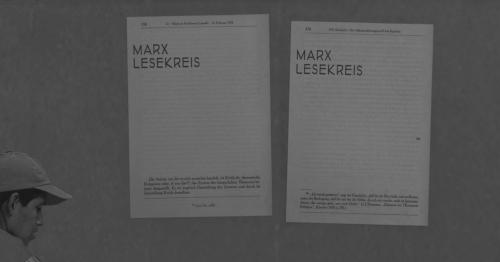

Between or indeed on the buildings huge statues of Marx project upwards again and again; on one building there is an enormous King Kong figure holding a sign bearing the word “Sale” between its mighty feet, and the letters G-W-G, which point to Marx’s theory of commodity exchange, are displayed in huge letters on high-rise buildings. On the road we see day laborers and construction workers, a marching band spreads across the street, and alongside it is Gael García Bernal in Michel Gondry‘s “La Science des rêves” (“Science of Sleep”) with huge hands apparently beckoning at the band. On the cold walls and site fences hang political placards and banners from a Marx study group (the camera gets so close to these that we can read them), or Leftist slogans (“Fight Back”, “Human Capital to the People”, “Smash Capitalism”) are displayed.

Holger Wüst, The Social Democratic Way of Thinking. An Image as a Film, 2012, Image via holgerwuest.tumblr.com

The work leaves open the question of whether Wüst is illustrating his interpretation almost by taking stock of the Social Democratic way of thinking or whether the observer is actually being shown “The Social Democratic way of thinking” objectively in the sense of a Social-´Democratic view of the world. One way or another, it's a dreary yet fascinating world: consisting exclusively of concrete, relating purely to human beings (with a striking absence of any sign of nature), overcast.

Inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo”

Holger Wüst has chosen Chris Marker’s film “La jetée” (“The Jetty”) from 1962 as his favorite film. With one exception, the film by the French photographer, essayist and multimedia artist consists of photo prints, which are woven into a photo montage to create a sci-fi story, which is narrated by an offscreen storyteller. The action is inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s movie “Vertigo”, and itself was a great influence on Terry Gilliam’s “12 Monkeys”, which can be considered the remake of “La jetée”.

Holger Wüst, The Social Democratic Way of Thinking. An Image as a Film, 2012, Image via holgerwuest.tumblr.com

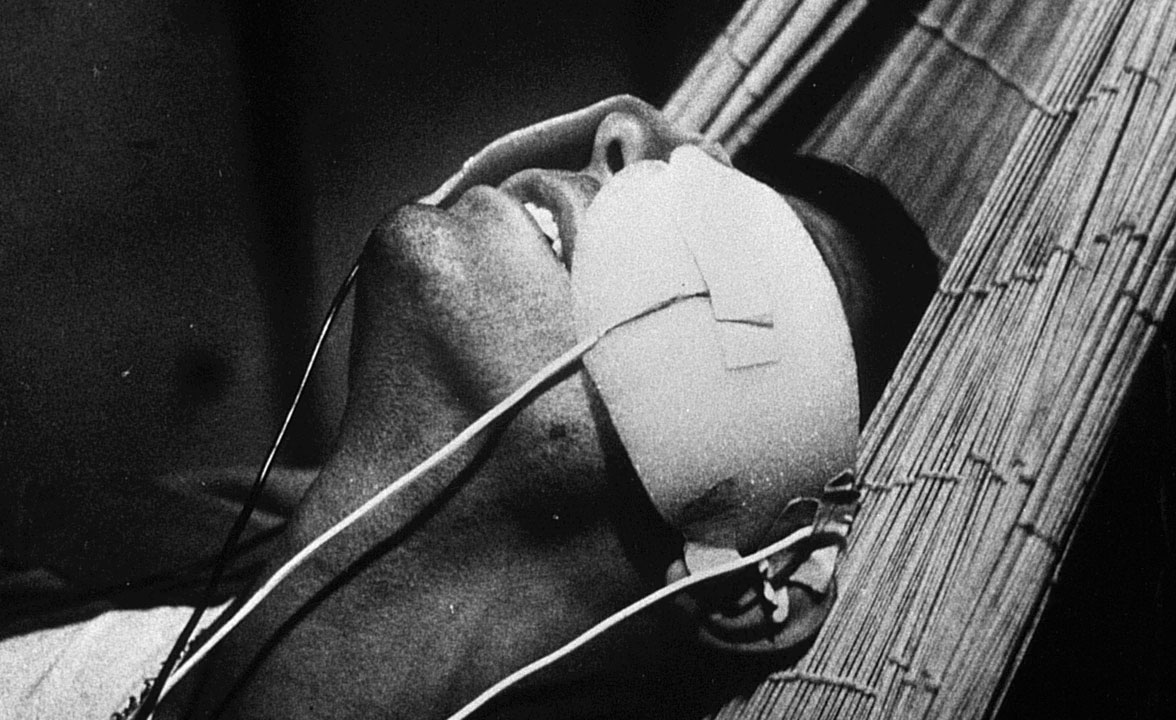

Chris Marker, La jetée, 1962, Filmstill, Image via sf-fan.de

Viewers are told the story of a nameless prisoner (Davos Hanich) who, following the Third World War, is living with survivors in the catacombs of Paris. The man is obsessed by an early childhood memory of an encounter with an unknown woman at the city’s Orly airport and experiences repeated flashbacks. These severe mental conditions awaken the interest of scientists who are looking for people to take part in their time-travel experiments: They see the prisoner as a suitable candidate for their experiment, which so far has caused all its testers to go mad as a result of the powerful mental impressions it creates. As he travels to the future and the past, the prisoner ultimately comes ever closer to his own childhood secret.

Film is 24 lies a second

The poetic “photo novel” is still considered a masterpiece and, with its contrasting black and white photography and its idiosyncratic mode of storytelling, it knows how to draw the viewer under its spell. Both Chris Marker and Holger Wüst use photography as a starting point for film and, in their way of working, create single images in a dual sense: firstly through the various different images and zooms themselves, and in a technical sense however, in the transfer to the analogous or digital film format, which for each medium consists of 24, 25 or 30 single images a second. Regardless of whether you believe French filmmaker Godard (“Film is 24 truths a second”) or the Austrian Michael Haneke (“Film is 24 lies a second”): an aura of truth clings to the magic which the single image harbors and which manifests itself explicitly when the one merges with the mass of other single images to create a whole, and this aura can be found in both works. Whether that is perhaps what is meant by the “social-democratic way of thinking” is something everybody must figure out for themselves.

Chris Marker, La jetée, 1962, Filmstill, Image via passiveaggressive.dk