The logic of fame most likely follows the same principles in the art world as it does anywhere else. Put a name on it: Dalí, the father of all Surrealists. Warhol, the inventor of Pop Art. Van Gogh, the founder of modern painting (and, of course, there was that thing with the ear). Monet, the very personification of the Impressionists and, for the sake of mentioning a female artist too: Kusama, the master of the dots. Let’s ignore the fact that such pigeonholing is always represents a reduction of reality. If you follow this simple logic, then it’s no wonder that Broncia Koller-Pinell is listed as one of the most important Austrian artists of the turn of the 20th century – even though her name has by now largely slipped into obscurity (hence Koller-Pinell’s name consequently also appears on another list, namely Julia M. Johnson’s “The Forgotten Women Artists of Vienna 1900”).

Broncia Koller-Pinell, Self portrait, before 1930, Image via wikimedia.org

Any attempt to attribute a specific style to her is doomed to failure: The painter was influenced by a huge variety of artists and artist groups, but did not follow any particular school, nor did she like to align herself entirely with social trends such as the nascent Feminist movement. Exchange and process in artistic practice seem to be more important than permanent self-positioning. This circumstance, but undoubtedly also the mere fact that she was a woman, made Broncia Koller-Pinell and her work the butt of criticism: A frequent accusation was that a lack of direction and arbitrariness made her a dilettante. In spite of this, during her lifetime she was considered one of the greats within the Vienna art scene, and she was to have a considerable influence on later world-famous painters such as Egon Schiele.

Interaction and process

Broncia Koller-Pinell benefitted not least from her liberal family background: At a time when women were basically denied access to art schools and could at best hope to study a selected applied art, her father Saul paid for her to have private painting lessons. She was born Bronisława Pineles in 1863 in what was then Austrian Galicia, and a few years later the family moved to Vienna. In 1885, the so-called “Ladies Academy” at the Munich Kunstverein presented the young painter with the opportunity to further professionalize her skills in a single-sex art class.

Even early on, her work was known to a broad public: By her mid-twenties she had already taken part in the international art exhibition in Vienna, and later she was presented at the legendary Miethke Gallery, one of the most important venues of Austrian Modernism. Koller-Pinell eagerly absorbed the emerging ideas and change of direction in art; she took in the work of the French Impressionists during her various travels within Europe, but was also influenced by the lively scene in Vienna with groups and movements like the Secession and the Vienna Workshops.

Outrageous nudes

Her artistic repertoire is hard to summarize in terms of a style; indeed it is more like an attitude: Koller-Pinell closes in on the subjects of her paintings from a kind of emphatic distance. They are often people and often stand alone in the picture. The result is an atmosphere that is not infrequently melancholy, feminist interpretations pick up on it as a visualization of the situation of women in society at that time: The woman remains imprisoned in the home, alone, but in this moment the painter makes her not a mere victim of circumstance, but rather shifts the personal characteristics of her portrait subject into focus. The interior in the background, on the other hand, is given little attention: Sometimes she paints a few stripes on a wall, but often it remains one and the same color. This is another way in which the relevant person in the picture is given particular significance.

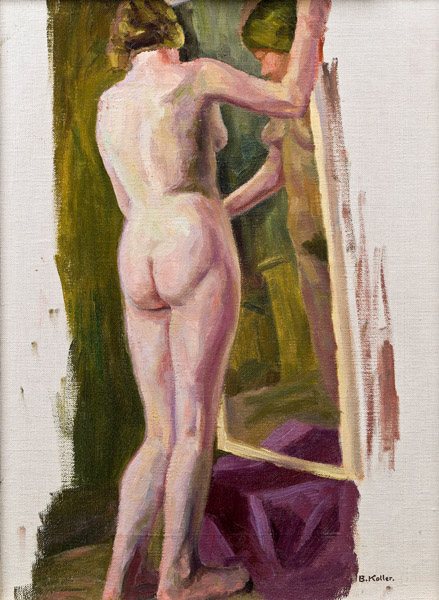

Broncia Koller-Pinell, Nude standing in front of a mirror, 1934, Image via wikimedia.org

One of the artist’s calling cards, which in the society of the day were considered outrageous, are her nudes: As the taboo of allowing women to study at art schools was gradually overcome, Broncia Koller-Pinell was already breaking the next, in this case, unwritten rule, that women should most definitely not be looking at naked bodies. Nudes therefore play an important role in the artist’s oeuvre and feature in all decades of her creativity, from the turn of the century through to her “Nude Standing in Front of a Mirror”, painted in 1934 shortly before her death.

The almost photographic eye

Alongside portraits and nudes, the Viennese artist also painted interior and exterior views, still lifes and street scenes. While her portraits focus entirely on the person displayed, here, in contrast, Koller-Pinell sticks to the interior or the view of the buildings: People rarely feature in the images. Her woodcuts to be seen in the current SCHIRN exhibition also convey a certain melancholy. What’s thrilling is the virtually photographic eye with which the detail is positioned: The snow-covered roofs, the market scene, even the sleeping girls all offer just a small insight into an evidently much bigger panorama. Here too Broncia Koller-Pinell’s hugely modern viewpoint is revealed at a time when the first photographic cameras were just being launched on the market for a wider public.

A delightfully mean reference that targets the person and thus also the work is the empty phrase “wife of…”. Knoller-Pinell is also supposed to have been referred to once by a male friend as “the talented wife of a famous man”, which may even have been well-meant.

The Koller family salon: Where artists came and went

Yet that friend may nevertheless have been allowed to remain a visitor to her salon, since the painter loved discussions: The house she inhabited with her husband Hugo Koller was frequented by artist colleagues and intellectuals, musicians, philosophers and apparently even the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud. Alongside her extensive travels, this was the place where Broncia Koller-Pinell made new acquaintances, gained new impressions and ideas, and passed them on to others. Later her children, particularly Silvia, and their partners (her son Rupert married the daughter of Gustav and Alma Mahler) also became important discussion partners. The meeting point was not Vienna, but rather sleepy Oberwaltersdorf located around 35 kilometers outside the city gates. It was here that Broncia’s father Saul owned a small textile factory which, after his death, was rearranged and converted into a salon by the artist and her friends, including Josef Hoffmann and Kolo Moser. The debates at the Kollers’ home are said to have been lively and legendary, and there has even been the suggestion that they stimulated no less a person than Egon Schiele in his work.

Broncia’s Koller-Pinell’s personal situation changed at the latest by the end of World War I: The growing antisemitism in Austria was felt ever more keenly by this Jewish artist and her family and children. She did not experience the World War II, since she died in Vienna in 1934 – and has, along with her work, been largely forgotten, perhaps not entirely by chance. Along with her gender, this may have been down to the fact that Broncia Koller-Pinell was Jewish and, what’s more, came from an affluent family, as the painter Albert Paris Gütersloh pointed out: Her work, he claimed, was therefore unable to gain the esteem of a specific (and for the painter clearly predominant) public. It was only in 1961 that the artist was posthumously assigned a major exhibition in Vienna, initiated by her daughter Silvia, who aimed to revive the memory of her mother’s oeuvre.