Swedish artist duo Nathalie Djurberg and Hans Berg has been working together for 15 years. With their cooperative working method they look back on a relatively young art historical tradition. Only with Modernism the trend towards creative collaboration between artist couples started to evolve – often transcending the then notions of classical coupledom. So what role did gender relations play in all of this, and how was that role reflected in the joint output? We look back a few years and introduce three artist couples of Modernism who each established their very own form of collaboration: Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova, Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, and Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy.

Love as construction

Alexander Rodchenko & Varvara Stepanova

“Under the protection of the labor union for equal work and equal pay for men and women.” (fig.) The revolutionary demand for gender equality in the course of the October Revolution is also decisive for the artistic practice of the Russian avant-garde. No other Western European Modernist art movement saw as many women featured as prominently as did the art circles of the early Soviet Union. Collaborative models of artistic production, oftentimes between life partners, further challenged the ideology of the creative individual, which was primarily related to the male artist-subject.

The relationship between Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova may be regarded as the model per se for an egalitarian couple relationship that simultaneously functioned as a work and life partnership. Not only did Rodchenko and Stepanova work together artistically in a range of media, they also allowed their collaboration and equality as life and work partners to be reflected thematically in their art. For instance on a double portrait from 1922, the two were photographed wearing fashionable unisex pullovers.

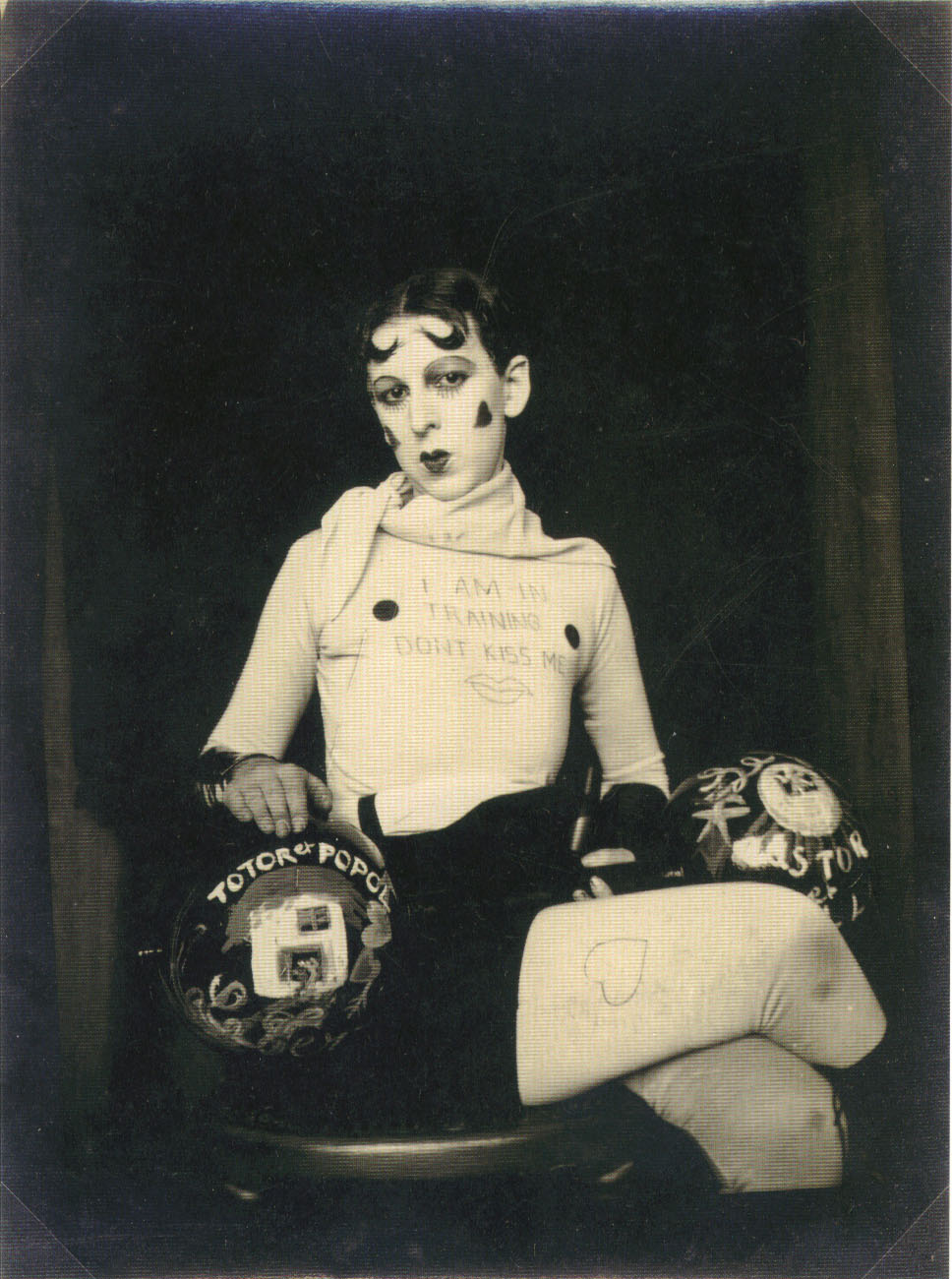

Varvara Stepanova, self-caricature as production-aesthetical clown, 1924 presse.leisurecommunication.at

Of course the representation of gender equality seldom corresponds entirely with reality. Rodchenko was considered the creative head of the couple, dictating his ideas and designs, which Stepanova noted down. The egalitarian vision inevitably also collided with the ideal of production art, its rationalist tendencies and male connotations. The enduring hierarchies in the self-portraits of this particular artist duo partially also led to playful enactments of the gender roles, as can be seen in Stepanova’s works.

Double-portrait Rodchenko und Stepanova, 1922, Image via art1.ru

In her drawing “Rodchenko as constructor” (1922) she caricatures the air of the disegno genius by showing him as a dainty mannequin busy at the drawing board constructing the new society with the aid of a compass and ruler, while she appears as a stout housewife dressed in leisure wear designed by the artist herself.

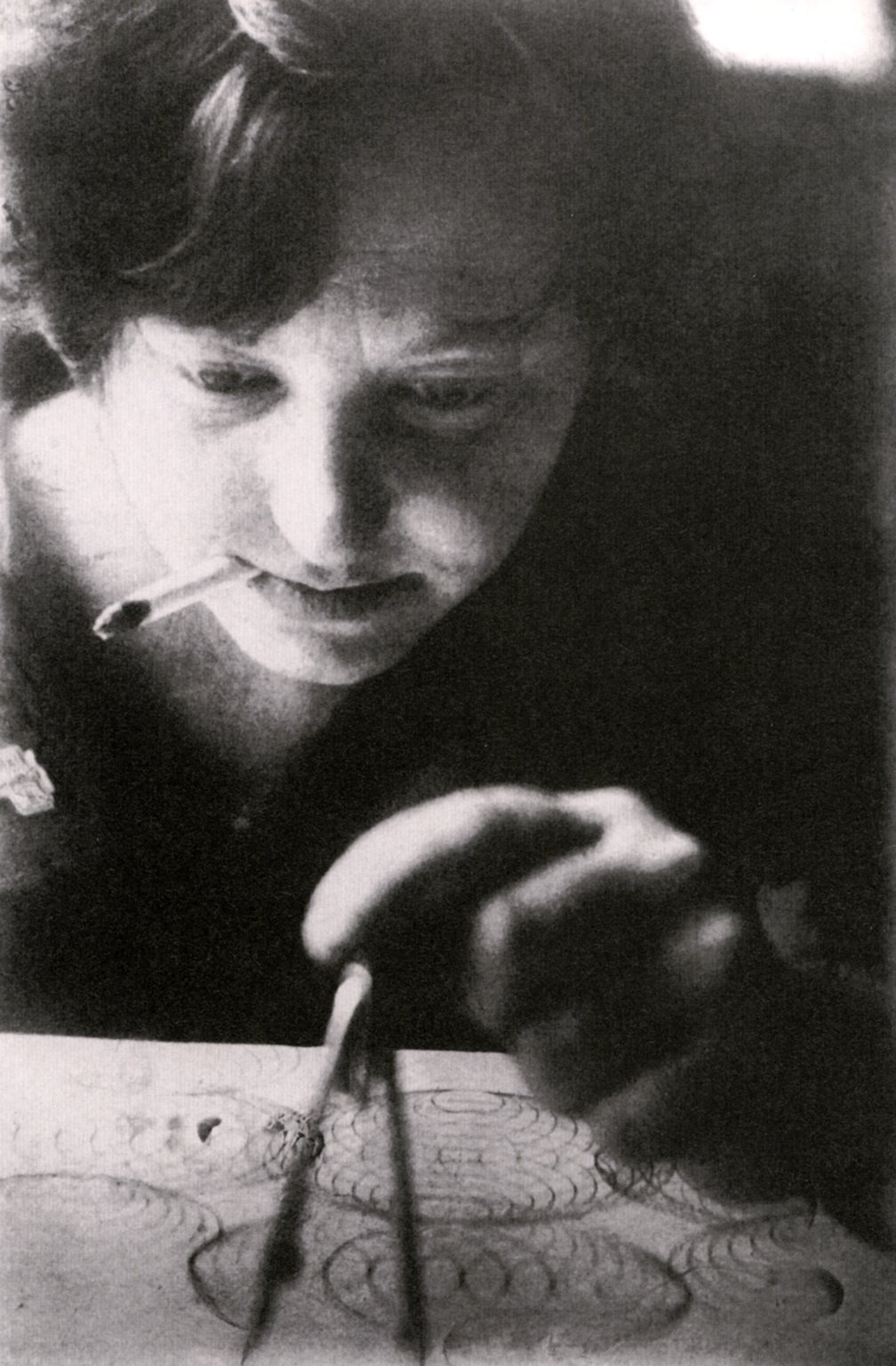

In Rodchenko’s photograph “Varvara Stepanova as textile engineer” (1924) we see the discrepancy between egalitarian gender politics and traditional gender roles come to light in an especially blatant way: The female engineer works on her geometric fabric patterns with a compass in her hand (as a symbol of construction with its male connotations) and a cigarette in the corner of her mouth (as a symbol of women’s emancipation) – yet in contrast to the rationalized aesthetics of Constructivism, the photograph aims to create sensuous effects and eroticizes its subject. Hand and compass as tools of precise geometric construction are rendered blurry in the shot, while the female producer takes center stage as an aesthetic object.

Alexander Rodchenko, Varvara Stepanova as a textile engineer, 1924, Image via tumblr.com

„L’autre moi“

Claude Cahun & Marcel Moore

Comparing the intra-couple relationship between Rodchenko and Stepanova and that between Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore is is like comparing Judith Butler’s Deconstructivist feminism to the views of Socialist woman’s rights advocate Clara Zetkin. The call for political equality is superseded by making sexual difference the subject for discussion. This shift is reflected in Cahun’s and Moore’s visual content: Their Surrealist oeuvre is characterized by figurations of the visual, doublings, multiplications and imitations, by rhetoric of eye and mirror.

When Suzanne Malherbe and Lucy Schwob met in 1910 it was to be the beginning of a lifelong partnership and artistic collaboration. From this point onwards they appeared under the male pseudonyms of Marcel Moore and Claude Cahun. Their most important work is the book “Aveux non Avenus,” published in 1930, a collage made up of autobiographic and poetic text fragments by Cahun, to which Moore added esoteric and enigmatic photomontages.

Claude Cahun and Marcel Moore, Aveux non avenus, 1929-1930, Image via artsearch.nga.gov.au

Claude Cahun, Que me veux tu?, 1929 © Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Image via metmuseum.org

Yet the interplay of text and image did not give rise to an authentic self-image and instead to a chain of fragmented reflections in ever new masquerades. The “you” addressed in the text returns time and again as the “other self,” the love relationship is that of two narcissists in the “magical mirror”.

Moore was behind the camera for most of Cahun’s self-portraits. The images enact the ambivalence of sexual identity. Cahun appears as the imitator of her many doubles. A line in “Aveux non Avenus” reads: “underneath this mask, another mask”. Yet it is not sexual identities as such that are staged, but the process of their performative production, the work of travesty. The image and text montages of Cahun and Moore theatrically enact an imaginary, pluralized subjectivity, which is at the same time carried by the cooperative collaboration between the two artists.

Claude Cahun, self portrait, 1927, Image via blogspot.com

Surreal Doubles

Marcel Duchamp & Rrose Sélavy

The work of Marcel Duchamp also revolves around multiple sexual and artistic identities. Like Cahun, Duchamp employed the self-portrait as a form of travesty. A portrait created in collaboration with Man Ray in 1920 shows the artist Duchamp as Rrose Sélavy, his alter ego, in whose name he signed some of his ready-mades around this time. In his self-representation he destabilized traditional notions of male artistic geniuses and staged himself as a split subject.

Alongside Rrose Sélavy, this can also be seen in Duchamp’s numerous puns centered on his first name. As the appellation of a certain person, a first name always also reverberates with the idea of the indivisible identity of an individual. We can thus assume that the title of his most important work, “La MARiée mise à nu par ses CELibataires, même” is also a linguistic play with his first name.

Man Ray, Rrose Sélavy, 1920, © Man Ray Trust / Philadelphia Museum of Art, USA, Image via wordpress.com

The split artistic personality is further invoked in the “assisted” ready-made “Monte Carlo Bond” (1924): The self-portrait shows Duchamp in front of a roulette table transformed into a demonic faun with the aid of shaving foam. The doubled artistic signature marks the work out as a cooperative one. Yet this relationship is also characterized by a hierarchical structure: Duchamp signs as the corporation’s “board member,” while Rrose Sélavy appears as the “chairwoman of the board”.