With the ranks of closed museums during the Corona pandemic, the idea of a digital exhibition took on concrete form, and ideas about digital exhibitions gained a very particular relevance. If people can’t go to the museums, the museums must come to the people. Naturally, this not only applies to art but almost the entire spectrum of social life, which is increasingly taking place virtually and is transported into our homes via delivery services. The museum of the future appears as a digital museum. Does this ultimately signal the long-feared downfall of exhibition venues for contemporary art, indeed of museums per se? Or are they being compelled to take on new functions of representation and communication?

The history of the elimination of cultural institutions dates back at least to the year 1917 when Marcel Duchamp planted a standard urinal bearing a hand-painted signature in an exhibition. Duchamp was not only hugely reluctant to show his works in exhibitions but – perhaps bolstered by this reluctance – also harbored a fundamental interest in the idea of the exhibition per se. As is evident from photographs, the artist behind the ready-mades considered his apartment/studio to be an exhibition space so that he might review the presentation of each urinal or snow shovel there.

Duchamp saw his apartment as an exhibition space

When he showed the urinal signed with the name R. Mutt in 1917 in an exhibition by the “Society of Independent Artists”, even though the work was actually not authorized, he was less concerned with the presentation of a work he had produced and more interested in placing a previously unlikely work of art – namely a standard retail product – within the art system. A similar strategy lay behind his activity as an exhibition designer – viewed from today’s perspective, this would equate to the collaboration between curator and exhibition architect.

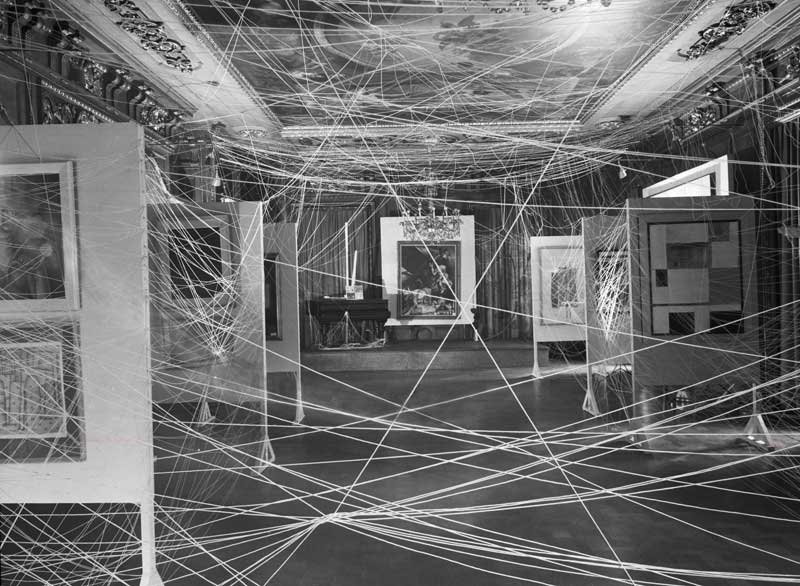

Two Surrealist art exhibitions that have long since become legendary are testament to this: At the “Exposition Internationale du Surréalisme” (1938) in Paris, 1,200 sacks of coal hung from the ceiling, the content of which fluttered down gently onto the visitors while the works by the exhibiting artists in the darkened space could only be viewed with torches. For the New York exhibition “First Papers of Surrealism” (1942), meanwhile, Duchamp distributed partitions throughout the space for the paintings and wove a 2.5-kilometer-long white rope into a giant spider’s web, which hampered movement around the exhibition and people’s views of the works considerably.

The normative ideas of exhibitions are revealed

Duchamp’s interest in the notion of an exhibition was made up of three elements: the significance of the individual artwork, the combination of works by different artists, and the notion of institutional representation and framing. In light of this, one of Duchamp’s works that represents a mobile museum, so to speak, is particularly relevant for my purposes: It is the “Box in a Valise” (the full title is “De ou par Marcel Duchamp ou Rrose Sélavy / La Boîte-en-valise”), created between 1935 and 1941 and made of 2D and 3D miniatures of the artist’s own pieces. What brings all these strategies together is a penetration into the realm of the art institution that exposes and shifts the normative preconceptions of appropriate presentation and aesthetic experiences. A second idea also related to Duchamp’s questioning of the significance and representation of art is André Malraux’s idea of the “Imaginary Museum”, created between 1948 and 1952. The Imaginary Museum (“of World Sculpture”, to give it its full title) is a forerunner of the online catalogue many museums now provide of their own collections.

John D. Schiff, Installation view of First Papers of Surrealism exhibition, showing Marcel Duchamp’s His Twine 1942, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Image via www.tate.org.uk

Marcel Duchamp, de ou par MARCEL DUCHAMP ou RROSE SÉLAVY / Boîte-en-Valise (Von oder durch MARCEL DUCHAMP oder RROSE SELAVY / Schachtel im Koffer), 1966 © Association Marcel Duchamp/ VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2018, Image via www.staatsgalerie.de

In the reproduction of artworks by means of photography, Malraux saw the possibility of producing a global museum in book form. The actual point of a museum that can be viewed anywhere and everywhere, according to Walter Grasskamp, is that it “[…] overrides the local rootedness of the objects in reproductions and allows them to be combined with one another at random […]”. Malraux himself emphasized the relationship developed over time between the museum and the artwork and a viewing regime entwined with this, which the Imaginary Museum contradicts to a certain extent by making new variations possible.

Even the invention of the museum, however, has caused a shift in context, whereby the work is removed from its original sacred, ritual or decorative function and transferred to a different location, that of the museum. The fact is, however, that the imaginary museum does not replace the museum with the original. “A serial reproduction expands our knowledge more than it satisfies our observation,” says André Malraux. Hence while Walter Benjamin, to whose essay “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility” (1935-6) Malraux refers, believed that photography destroys the uniqueness of the original, the “Imaginary Museum” treats its works as legitimate conversions of the three-dimensional into the two-dimensional. Malraux’s handling of artworks, which drew criticism from many sides, consists primarily, I believe, in the (curatorial) compilation of various works and the use of a kind of family resemblance, into which he incorporates objects that are independent of one another in terms of time and culture and thus generates not only a stylistic device but also new meaning.

A serial reproduction expands our knowledge more than it satisfies our observation.

Maurice Jarnoux, André Malraux in the midst of photo reproductions for his book "Le Musée imaginaire", ca. 1947, source: MACBA Barcelona, Image via www.kunstgeschichte.hu-berlin.de

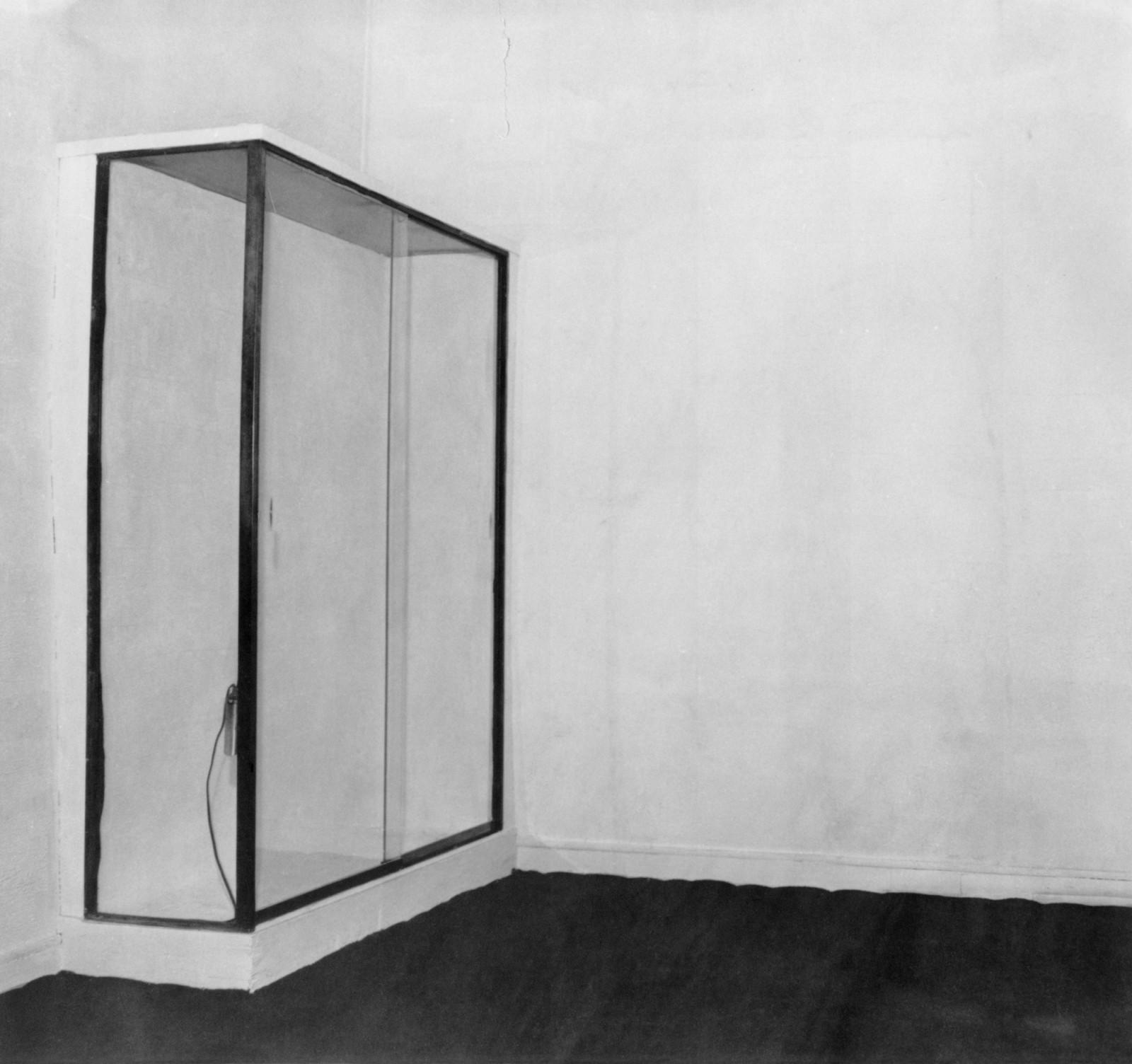

The exhibition without works by Yves Klein at Parisian Galerie Iris Clert in 1958 is, according to the art historian Nuit Banai, the most important work of his career. “Where art is concerned,” she argues, “the audience did not have the historical distance to recognize that Klein was contributing to the development of artistic forms such as the happening, body art, minimalism and earth art – forms that would become popular over the following ten years and which place the focus firmly on the human body in the space.” As the name of the work “Le Vide” (French for “the void”) suggests, the small space of the gallery was empty: whitewashed walls, an empty glass case and a white curtain without a single painting by the artist, who was famous for his monochrome works.

Yves Klein turned an empty gallery into an art spectacle

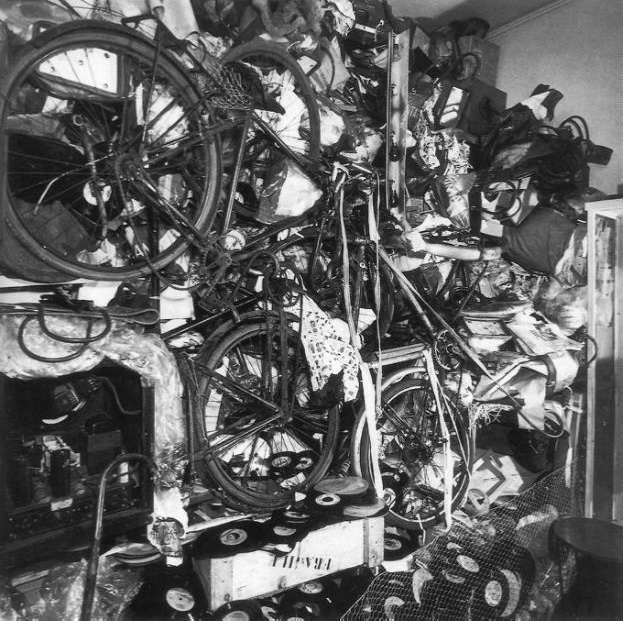

Nevertheless, it was precisely due to and above all through the spectacular staging – admission either with an invitation or upon payment, limited entry for a maximum of ten visitors at any one time, tight security on the door, and not forgetting the presence of the artist himself – that the exhibition was still relatively well-attended, at least by today’s standards. Klein’s investigation of the exhibition space, its impact on the exhibited works, and the significance of the producers present is of fundamental importance in art history. Further artistic examination of the gallery space was all the rage during the 1960s. In 1960, the object artist and cofounder of Nouveau Réalisme Arman, not only exhibited in the same gallery as Yves Klein had previously, but also made direct reference to Klein’s void, whereby he presented the gallery full to the ceiling with garbage (broken bicycles, empty beer bottles, water pipes, old records, etc.), making it virtually inaccessible. Even the title Arman chose for the work “Le Plein” (translated as “Full Up”) is like an aesthetic response to Yves Klein’s void. The foundation of Nouveau Réalisme likewise came about in 1960, and the group of artists to which Yves Klein also belonged subsequently dedicated itself to the transformation of unsightly waste into pleasing art.

Yves Klein, Le vide, Galerie Iris Clert, Photo : © All rights reserved © The Estate of Yves Klein c/o ADAGP, Paris, Image via www.yvesklein.com

Arman, Le Plein, Galerie Iris Clert, 1960, installation view, Image via artnote.eu

In 1966, New York’s Leo Castelli Gallery, which had been founded in 1957, allowed Andy Warhol to set afloat a number of silver foil, helium-filled balloons shaped like cushions, the space-consuming, reflective, enlivening and occupying nature of which means they can be considered forerunners of the immersive installation.

„during the exhibition the gallery will be closed“

Another barricade in front of the entrance to the art space was created in 1968 by the concept artist Daniel Buren, who used laterally hung, overlapping strips of fabric. Even before this, Buren had used his now iconic strips to pursue a kind of anti-art that appealed against any kind of artistic mythology. One high point of this anti-functionalist art, later to be institutionalized as institutional critique, is the unequivocal and literal closure of the Eugenia Butler Gallery in Los Angeles in 1969, undertaken by another concept artist, Robert Barry. Barry had a notice placed on the door of the gallery stating “during the exhibition the gallery will be closed.” The same wording appeared on the invitations and the press information.

Nat Finkelstein, Andy Warhol and Silver Clouds in Castelli Gallery, 1966, Image via www.timeout.com

The cognitive paradox of accentuation through concealment or diversion is a defining element of the work of Christo and Jeanne-Claude. In 1969 they wrapped up the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, naming the work “Wrapped”. According to the author and artist Brian O’Doherty, with this work the artist couple were reflecting on the crisis of an institution that was becoming ever more like a business. If, therefore, the building itself becomes the work of art and reveals its inner workings, then it’s not a far cry from a digital takeover, even if the intervening period has actually been used for the construction of spectacular museum buildings in many places, starting with the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, which began hosting exhibitions in 1997.

The gallery space loses its neutrality

In time lapse the genealogy of showing art could be broken down into the following steps: church, museum, exhibition, architecture, computer. The significance of the white, empty gallery space for the art exhibited there was first determined by Brian O’Doherty with his essay “Inside the White Cube” (1976-81), which appeared in several parts in the magazine Artforum. In it, he asserted that this ideal space dominated over art and was actually the true accomplishment of Modernism. This was preceded, he claims, by the salons of the 19th century, which placed the image at the fore. Set in striking frames, the paintings covered the entire wall, whereby each single one was perceived as an independent unit. With the onset of Postmodernism, the gallery space begins to lose its neutrality.

Robert Barry, Closed Gallery, 1969 (c) Robert Barry, Image via www.wikiart.org/

Christo and Jeanne Claude, Wrapped Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, 1968-69, Photo: Dave Fornell (c) 1969 Estate of Christo V. Javacheff, Image via christojeanneclaude.net

“The wall becomes a membrane through which esthetic and commercial values osmotically exchange. […] The ideal gallery subtracts from the artwork all cues that interfere with the fact that it is ‘art’. The work is isolated from everything that would detract from its evaluation of itself. This gives the space a presence possessed by other spaces where conventions are preserved through the repetition of a closed system of values,” says O’Doherty. One important aspect for this investigation, namely photographic documentation of exhibitions, is perceived by O’Doherty to be “a metaphor for the gallery space”. The exhibition photo conveys the gallery as a closed system consisting of space and work and emphasizes this through the exclusion of human beings. The observation of artworks thus also tutors a perception of the space or, it might make more sense to say, the surrounding space.

The wall becomes a membrane through which esthetic and commercial values osmotically exchange. […]

Many years after O’Doherty, this space for exhibitions still remains, and it has provided for many more shifts in perspective on the part of both the artists and the makers of exhibitions. “Stillness, emptiness, silence: In the overabundance of today’s image society, the pause, the gap – the nothing between the things – gains in importance.[...] Faced with a reality that is becoming ever less tangible in its complexity, this skepticism is expressed in strategies of refusal as well as in the negation of representation.” This assessment by curator Martina Weinhart from the year 2006 is intended not to criticize the functional system of art as such, but rather to trace the path on which art apparently increasingly delegates its own observations to the exhibition space and thus fills it with as little material as possible.

One of the works in this group exhibition that displays the least is “Zeigen” (engl. “Showing”) by Karin Sander. The work made up of works by other artists, who have described their own works only in words, and can be heard by the observer by means of an audioguide corresponding to the relevant label displayed on the wall. In 2016, Maria Eichhorn paraphrased the above-mentioned work by Robert Barry. For her exhibition at London’s Chisenhale Gallery, Eichhorn distributed the budget provided for production among the workforce of the exhibition hall so that they could stay away from the work and do nothing at all for the exhibition hall, as per the artist’s instructions, without losing any money for the entire duration of the exhibition, set out in its title of “5 Weeks, 25 Days, 175 Hours”. The description explains more: Telephone calls are not being answered, incoming emails are being deleted, except for those going to an extra account, which will only be checked once a week.

Maria Eichhorn, 5 weeks, 25 days, 175 hours (2016). Installation view, Chisenhale Gallery, 2016, Photo: Andy Keate, Image via chisenhale.org.uk

Eichhorn’s concept explains that the institution and the exhibition are not closed in this way, but rather relocated to the public sphere. Unlike the vast majority of public art institutions, the Chisenhale Gallery is 100-percent funded by foundations and patrons, and this includes staffing costs. While Robert Barry, just like Maurizio Cattelan 20 years later, locked up a commercially operating gallery with almost zero percent public interest in order to disrupt the possibilities of conceptual art and an art system prone to innovative artistic concepts, Maria Eichhorn’s intervention relocates the economic foundation of the artistic production and its representation to the public sphere and thus creates an wholly public work of art.