Most travelers are looking for authenticity. This is the case today, and was the case over a century ago. Back then graphic artist and painter Emil Orlik traveled from Vienna to Japan – only to be disappointed. When he disembarked in Yokohama in spring 1900 he found a city “covered in a horrible modern veneer”, as he wrote in a letter to his friend Max Lehrs. One month later in Tokyo he moved into a hotel that could easily have been in Tuscany were it not for the blossoming cherry trees in the garden. Hotel Metropole was located in the Tsukiji district, right next to Tokyo Bay. Today the world’s largest fish market can be found here. At that time Tsukiji was a quarter that wholly met the tastes of European business travelers, with wide boulevards and hotels that looked like French chateaus or Italian villas. But that was not what Orlik wanted.

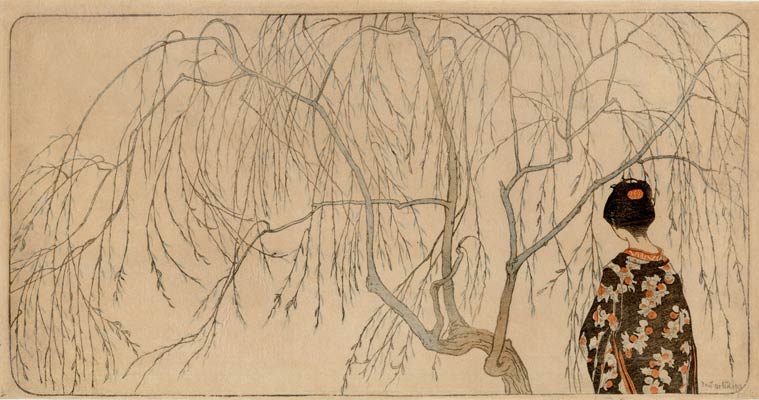

Emil Orlik, Japanese Girl under a Willow Tree, 1901, Image via orlikprints.com

Japan had long been somewhere Europeans had longed to go. Or at least the place from where fashionable products were imported, above all porcelain and textiles. In the salons of Europe during the period when all things East Asian were highly fashionable in the 18th century no one really cared whether the porcelain came from Japan or China. Soon objects à la chinoise were ubiquitous, made in Europe.

Pictures of the floating world

All that changed in the 19th century. Japanese prints were collected and traded for the first time. The avant-garde was in search of new forms a far remove from the academic oils that dominated exhibitions at the time. Painters and graphic artists no longer believed in the old European visual traditions. This was the perfect context in which the Vienna Secessionists could focus on art outside of Europe, East Asian art to be precise. They had seen the idea of a comprehensive reform of life in the British Arts and Crafts movement: the unity of art and craftwork, the extension of aesthetic criteria to cover of all walks of life. Here Japanese masters served as the role models.

Emil Orlik, Two Japanese Men - Rickshaw Drivers, 1900, Image via orlikprints.com

When Europeans thought of Japanese art at this time they generally associated it with the ukiyo-e woodcut. Ukiyo-e means “pictures of the floating world” and the genre’s best-known master is Katsushika Hokusai. To Europeans, these works appeared highly modern, yet the color woodcut had existed in Japan since the eighteenth century. The technique itself required just a few tools, but a great deal of practice. In Japan, unlike in Europe, it was not one artist who executed the template and the print, but three. A painter – Hokusai for example – took care of the template, while a woodcutting expert transferred the drawing onto the wood block and finally a printer applied ink to the panels. Orlik was fascinated by this distribution of work and depicted it in three graphics. For his contemporaries, the similarity of the two-dimensional, ornamental ukiyo-e woodcuts to Viennese prints was obvious. The ukiyo-e artists did not concern themselves with perspectives or the accurate depiction of nature. Rather, they focused on the beauty of the line and the clarity of the composition, as Adolf Fischer, a collector of East Asian art, explains in the catalogue of the sixth Secession exhibition. The Viennese artists and the Japanese masters came together, on paper at least.

Emil Orlik, The Painter, the Woodcutter and the Printer, 1901, Image via bertha-lum.org

Having arrived in Japan, Orlik sent postcards and letters, most significantly to his friend Max Lehrs. He supplied the graphics expert and art historian with small drawings and test prints. This correspondence tells us that Orlik wanted to get away from Tokyo. He studied Japanese, left the capital city behind him, and headed for the country’s interior. The further into the hinterland he progressed, the more fervently he believed he had detached himself from European prejudices. Back in the spring he had taken a trip to the old temple city of Nikko north of the capital, and he found himself back there again later while fleeing the heat of the Tokyo summer. It was here that Orlik learnt the ukiyo-e art, and he managed to send the first prints to his friend Lehrs.

The real Japan

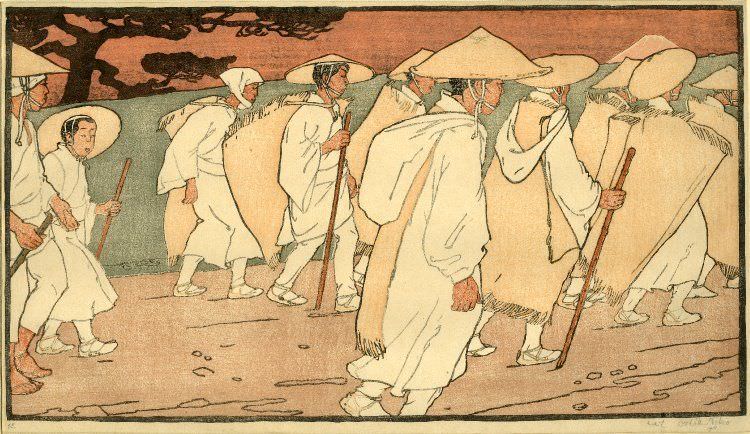

He was now convinced that he was able to understand what was specifically Japanese about the artworks, or so he said in a letter sent from Nikko in mid-September. For five weeks Orlik journeyed alone and on foot through Japan. He went to places where, he claimed, no Europeans had been for eight years. A gardener in the old temple gardens posed for Orlik, and the figure was multiplied ten times by way of a model for the woodcut “Japanese Pilgrims on their way to Fujiyama”. This was a topic that Hokusai had dealt with a hundred years before in his series about Mount Fuji, but Orlik changed the composition and printed his own version. He proceeded to rent a hotel room in Kyoto and spent the winter there, accumulating printing panels.

Emil Orlik, Japanese Pilgrims on the Way to Fujiyama, 1901, Image via artinwords.de

Katsushika Hokusai, Mount Fuji Viewed during a Fine Wind on a Clear Morning (Gaifû kaisei), from the series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjûrokkei), ca. 1930, Image via ids.lib.harvard.edu

As a native of Vienna, Orlik was himself an exotic foreigner in Japan. Art magazines published articles about him and his travel sketches. After his friend Adolf Fischer had introduced him to an art association in Tokyo, he was then even able to participate in an exhibition there. At the end of February 1901, Orlik headed back to Vienna as one of the few European artists to have undertaken a journey to Japan at that time. The critic Ludwig Hevesi found Orlik’s prints to be even more interesting now that he had learnt all those finishing touches in a Japanese printing house. Orlik may not have discovered the real Japan, but that is probably nothing but a product of the European imagination.