“Rooks have young. Young ravens fledged. Fork-tailed kite lays three eggs. Redstart sings for the first time,” wrote Gilbert White in his journal on April 17, 1768. For 25 years, the clergyman and naturist from Selborne in southern England noted the goings-on in his own garden on an almost daily basis. In the same period, William Bartram spent several years travelling through the southern colonies of Georgia, Florida, and what was later Alabama, carefully noting down his encounters with flora and fauna as he went.

Neither of them could have guessed that their detailed descriptions of their surroundings would make them pioneers of an entire literary genre: Nature Writing. Developing initially in the Anglo-American world, it gradually spread into other linguistic cultures – and with the increasing concern about climate change it has gained widespread popularity again over the last few years in Germany, too.

Scientific facts are deliberately mixed up

Here, the parameters have changed only marginally over two and a half centuries. From journals and personal experiences to essays and reference books, through to poetry and novels: In each case, a narrative voice adopts a subjective view of the nature in which it finds itself or which it seeks out for this purpose. That may constitute the subject’s own garden or the woods behind their house, close observation of a particular animal in its natural habitat, or examination of flowers or fungi. Often scientific facts are deliberately combined with natural history, philosophy, mythology, and personal anecdotes. This was the case with Henry David Thoreau, whose notes published in 1854 under the title “Walden: Life in the Woods” has long since become a cult book, and with T. H. White’s story of taming a wild animal, “The Goshawk” (1951), as well as Nan Shepherd’s love letter to the Scottish chain of mountains known as the Cairngorms in “The Living Mountain” (1977).

18th C. engraving of Selborne village, Image via www.sciencemusings.com

Nan Shepherd, Image via www.scottishreviewofbooks.org

Catharine Parr Traill is one of the few women to publish during the golden age of this genre. In 1832 she emigrated with her husband from London to Canada, where they settled on a patch of land close to Peterborough. Even during the journey there, she filled the letters she wrote to her mother back in England with pages-long descriptions of nature, which she published in 1837 under the title “The Backwoods of Canada”: “Some miles below Montreal the appearance of the country became richer, more civilized, and populous; while the distant line of blue mountains, at the verge of the horizon, added an interest to the landscape […]”

Muir’s observations appear unusually critical for the time

Like Catharine Parr Traill, who had gleefully immersed herself in the solitude and stillness of the dense forest, John Muir was also fascinated by the nature of Canada. Muir, who later found his way into the canon of “Nature Writers” with texts about the mountains of California and Yosemite Park, spent two years in Ontario from 1864. His observations about the settler’s methods in dealing with the trees appear unusually critical for the time:

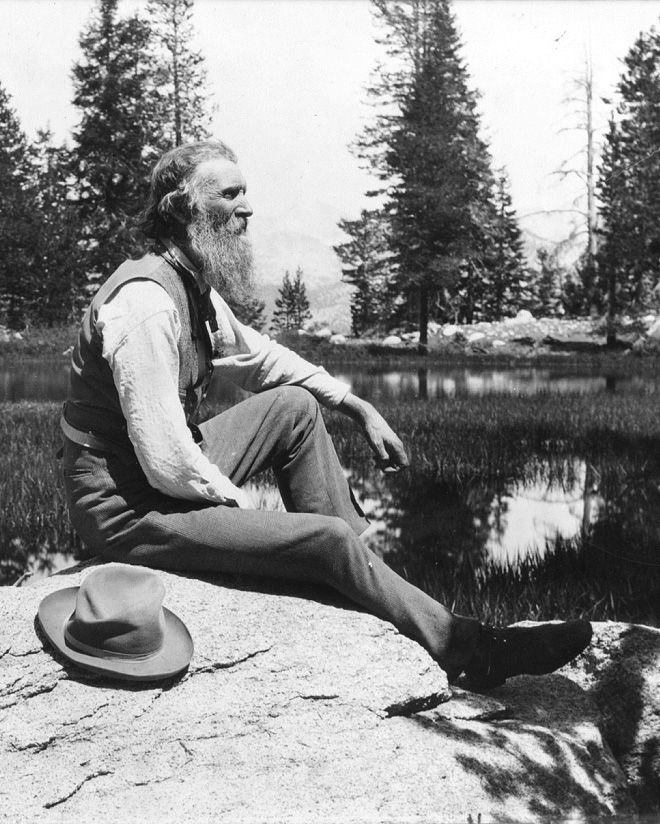

John Muir, c. 1902, Image via Wikicommons

“At first only a few acres would be slashed down--oak, ash, elm, basswood, maple, etc., of several species. On account of the closeness of the growth these trees were tall and comparatively slender, and the roots formed a net-work that covered the ground so closely that not a single spot was to be found in which a post-hole could be dug without striking roots. These beautiful trees were simply slashed down [...]”

Criticism also came from Emily Carr in her reportages published in 1941 under the title “Klee Wyck. (Laughing One)”, which document her travels along the coast of Canada around the turn of the 20th century. She travelled through the country in order to paint the totem poles of the indigenous populations and not infrequently lamented the deplorable living conditions of these people, who had been forced onto reservations by the ruling British. Time and again, she incorporates observation of nature into her texts. Hence, even though she gets horribly seasick every time, she remains fascinated by the primeval power of the sea:

“We heard a terrific pounding and roaring. It was the surf-beat on the west coast of Queen Charlotte Islands. Every minute it got louder as we came nearer to the mouth of the Inlet. It was as if you were coming into the jaws of something too big and awful even to have a name […].” Since the texts were written by Catharine Parr Traill and Emily Carr, social conditions in Canada have changed and are now only rarely a subject of Nature Writing; yet the writers’ fascination with the wilderness remains unbroken. When Chris Czajkowski built a log cabin in a remote part of British Columbia in the late 1980s, she found poetic words for the diversity around her:

“Like a Japanese ink painting, the little lake lies before me surrounded by a small forest of bent pine trees. It is almost entirely silted up and full of reeds but the turquoise water, which appears almost opaque as a result of the glacial dust, forms a harmonious contrast with the blood-red blooms of the Indian Paintbrush. A wall of ice behind it, ridged and cracked with age and no longer bearing any snow, hangs like a curtain before a dark wall of rock.”

Yet the effects of climate change are already becoming impossible to ignore – and are therefore a defining feature of the new Nature Writing. When Allan Casey undertook a trip through his homeland for his 2009 book “Lakeland” with the aim of researching the connection between bodies of water and the culture of Canada, the conditions had changed significantly since his previous visits. He recalls:

“The caribou used to be plentiful here when they came off the barrens and into the trees to their winter ground, squeezing between Lake Athabasca and Black Lake. […] More than a hundred caribou passed [back then]. For me, it was an exquisite, transformative moment of attachment to the earth, a simultaneous sense of belonging and of witnessing something divine.”

But this time, he doesn’t see any caribous; these sensitive creatures have taken another route since a road was built through their original habitat. Nature Writing can imply a form of escapism into idealizing, dream-like descriptions and can likewise succumb to the temptation to anthropomorphize animals. Yet along with the climate and the protests against the associated policies, a transformation is also underway in the literary critical appraisal of an environment that is threatened with outright destruction as a result of reckless exploitation by human beings.

The texts of Nature Writing could help us to regain our connection to nature and to ensure that we work harder to preserve it – so that the dense forests, raging rivers and wild animals we read about in such literature will still exist in 200 years.