Are artists especially creative when it comes to cooking? A glance in the kitchens of the art world. This time with a short chronicle of artists’ restaurants, from Daniel Spoerri to Jennifer Rubell.

Daniel Spoerri serves up 125 grams of bread

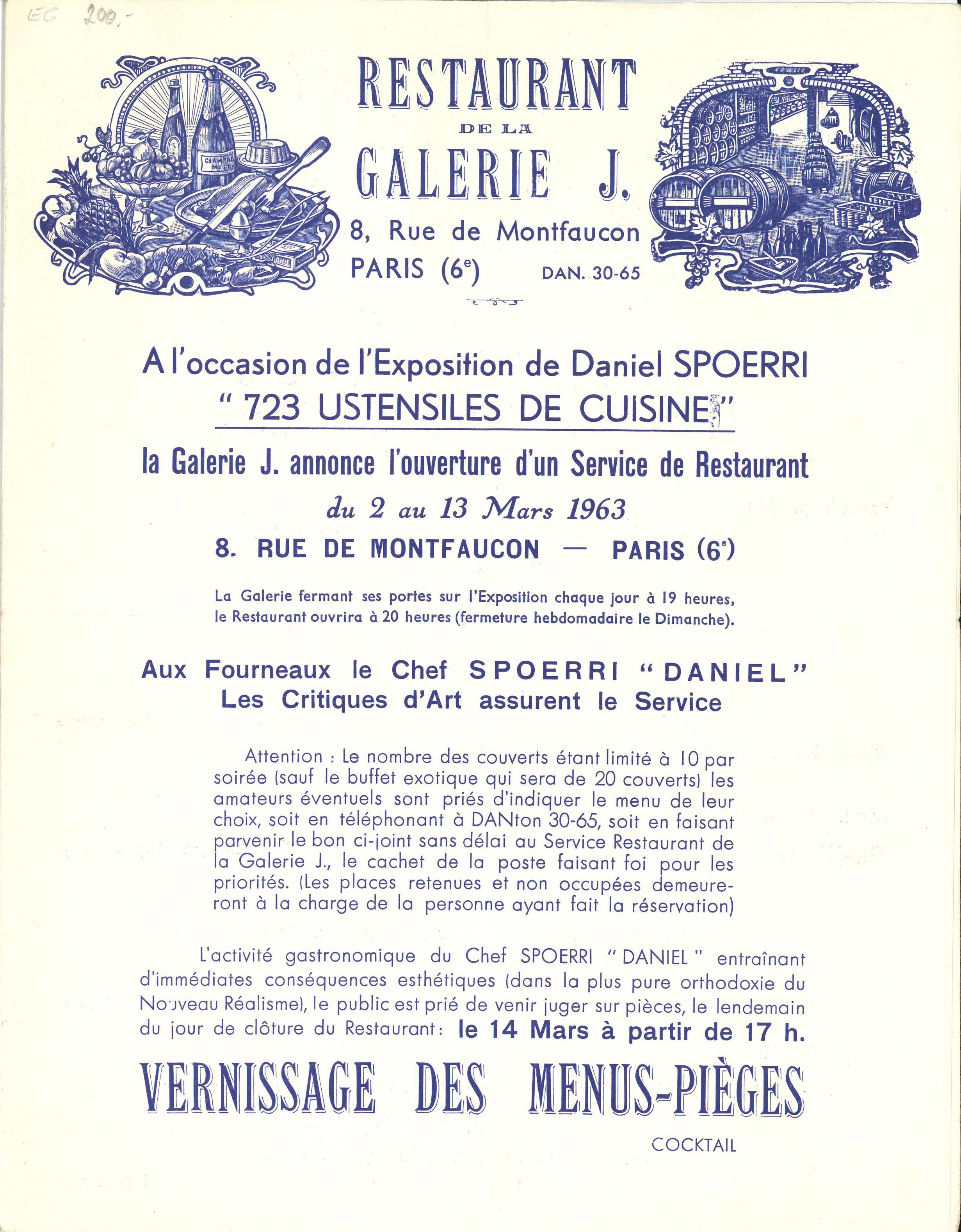

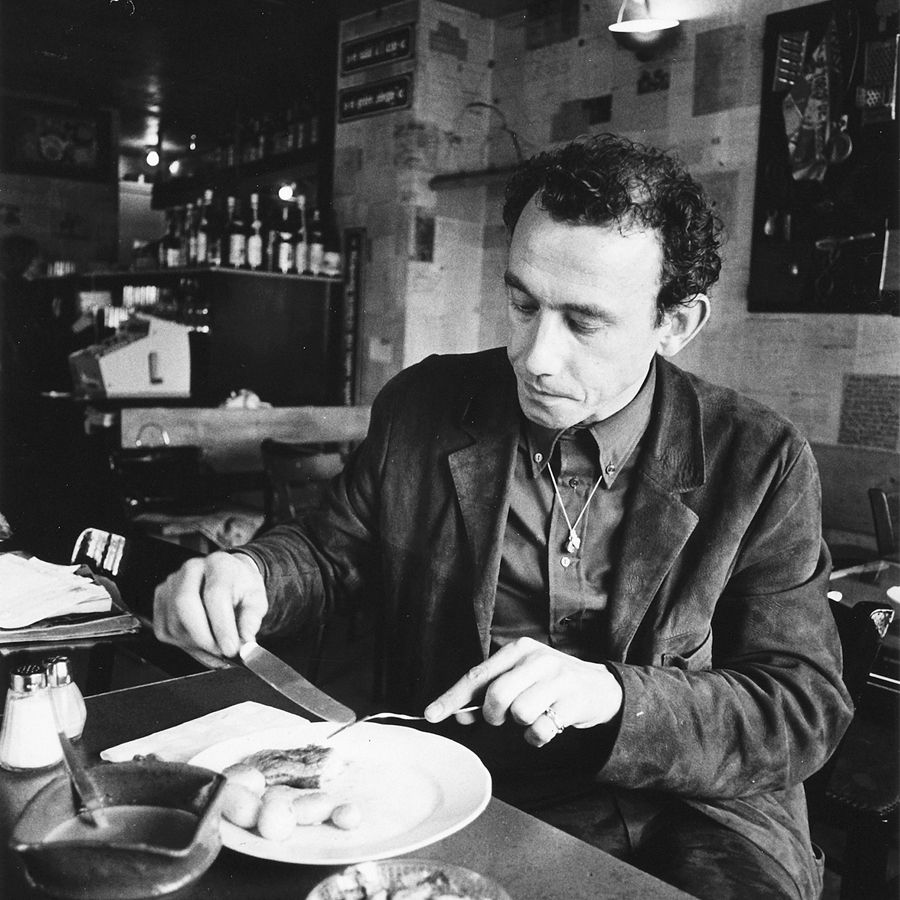

In early March 1963, Galerie J in Paris exhibited a collection of 723 kitchen utensils, from a meat grinder, or a potato peeler through to a cheese grater, it featured them all. Swiss artist Daniel Spoerri had collected them and mounted them on boards. He is co-founder of the Nouveau Réalisme movement and inventor of “Eat Art”, which describes an artistic approach to everything that is edible. As was customary, the gallery closed its doors at 7 p.m., albeit only for Spoerri to open them again an hour later to take the stage as “le Chef Spoerri Daniel” and lead his guests to a temporary restaurant. Over the course of ten days, each evening the artist donned his apron and cooked for ten guests each time: The themed menu varied and included “Franco-Niçois” (with pastis and Rocky Mountain oysters in cream) and a “prison menu” (thin cabbage soup and 125 grams of bread). He hired art critics to wait at table, as they usually worked as the intermediaries between the (eat) art and the public. Some years later, Spoerri opened a “genuine” restaurant in Düsseldorf and served not only steaks but also python schnitzel, ant omelets and snake ragout, with the intention of expanding his guests tastes. However, he no longer stood at the hob himself, but only acted conceptually. He called his artistic-restaurant project a “multimedia-super-happening artwork” and in this way made a not insubstantial contribution to shifting the parameters of art and bringing it closer to everyday life.

Invitation: Daniel Spoerri's restaurant in Galerie J, Paris, March 1963, image via ada-invitations.de

Daniel Spoerri, Image via Spoerri.at

Allen Ruppersberg and Les Levine serve filet of tree bark and Halifax salmon steak

In the 1960s, many young artists felt a similar impulse to place everyday places and objects at the center of their work. As an artist, the idea of donning the role of running a restaurant fitted perfectly into this age of artistic upheaval. In 1969, two restaurants based on this principle opened in the United States: Allen Ruppersberg’s “Al’s Café” in Los Angeles and Les Levine’s “Levine’s Restaurant” in New York. Al’s Café opened on Thursday evenings and resembled a classic American diner, although a glance at the menu revealed many a hard-to-digest meal such as “three rocks with a scrunched up piece of paper”, “filet of tree bark” or “cotton with stardust”, an ironic allusion to the Land Art movement evolving at the time. After an order was placed, Ruppersberg then prepared these sculptural meals and served them; guests consumed them at their own risk. That said, real beer was on sale and over the three months of its existence the café (part installation, part participatory performance) in this way soon emerged as a popular meeting point of the local art scene.

Allen Ruppersberg, Al's Café, 1969, image via allenmccollum.net

Les Levine, Les Levine's Restaurant, 1969, image via mutualart.com

Les Levine, Les Levine's Restaurant, 1969, image via artax.de

Les Levine’s establishment on the East Coast was open for longer, namely for a full half year, and the concept was “Irish-Canadian-Jewish” cuisine that thus drew on his own roots. He called the project an “autobiographical culinary environment”, the tablecloths were bright green, and dishes such as “Halifax salmon steak”, “diced chicken liver Levine” or “matzo dumpling soup” were served. Art critic David Bourdon deemed the food “deplorable” and the lighting “somber” but at least the prices are said to have been modest, and anyone sharing Levine’s name got a 20-percent discount. The artist wanted to create a relaxed, pleasant ambience, but he also installed five surveillance cameras and screened the footage in real time on several monitors that were spread around the room. Whether this was the reason why “New York’s only Canadian Restaurant”, so the adverts, was never a big splash is not known. Nevertheless, it functioned the way Levine wanted as it conveyed his concept of placing art in a social context that addressed all of the viewer’s senses and made them active participants in the piece.

Gordon Matta-Clark serves oxtail soup and frog’s legs

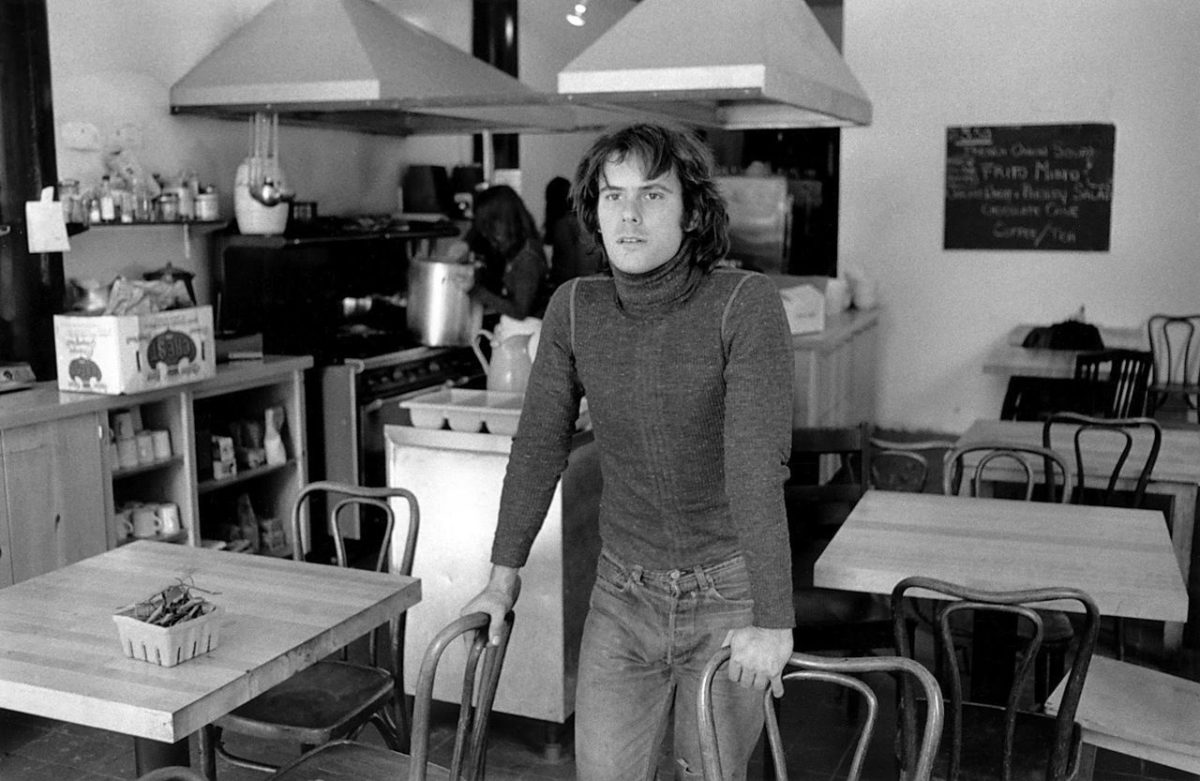

What was probably the artist-restaurant project of that era which ran for longest was “FOOD” (1971–3), opened by Gordon Matta-Clark, Carol Gooden, and Tina Girouard in New York’s SoHo district. It was run entirely by artists and was the only eatery in the district that offered healthy, sustainable, and affordable food; within a short space of time, the restaurant had become highly popular and a central meeting place for the creative scene. Matta-Clark organized regular performances there, such as his “Bone Dinner”, during which he served oxtail soup, followed by roasted marrowbone dumplings and frog’s legs. At the end of each evening, each guest was given a necklace made from the bones left on the plates. FOOD evidently succeeded effortlessly in functioning as a restaurant, a social experiment and a participatory artwork, whereby the latter term did not really gain sway until over 20 years later.

Tina Girouard, Carol Goodden and Gordon Matta-Clark in front of FOOD, Restaurant, New York, 1971; Photo: Richard Landry, Font: Gordon Matta-Clark; Image via openfileblog.blogspot.com

Gordon Matta-Clark at FOOD, image via somethingcurated.com

Rirkrit Tiravanija serves Pad Thai and herbal tea

At the end of the 1990s, art critic Nicolas Bourriaud subsumed all art conceived as the venue of social interaction and which absolutely requires active audience participation in order to be realized under the term “relational aesthetics”. Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija is considered one of the main proponents of this movement: In 1990, for the purposes of a temporary exhibition he transformed the Paula Allen Gallery rooms in New York into a pop-up kitchen where he served Pad Thai that he proceeded to cook himself. Some people are said to have thought Tiravanija was a caterer, which he was probably quite happy with because it was not his person, but the interaction between the visitors that was supposed to take pride of place. Since this first pioneering action, Tiravanija has repeatedly staged participatory works in which food and hospitality play a central role. In 2015, he set up a communal outdoor restaurant made of bamboo (“We Dream Under the Same Sky”) in front of the entrance to the Art Basel fair, where visitors were invited to pay for their meal and beverages (there was herbal tea from his own garden and Thai curry) by helping cook, serve, and wash the dishes. The short dissolution of the conventional hierarchies (curators became dishwashers, collectors became sous chefs) Tiravanija created an artistic utopia of collaboration and hospitality.

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled 1990 (pad thai), 1990, Opening at Paula Allen Gallery, New York, 1990, Courtesy the Rirkrit Tiravanija Archive; image via momaps1.org

Jennifer Rubell serves a vast range of brunches

Well before Tiravanija opened his Art-Basel pop-up restaurant, another artist had dedicated herself to providing the public at the Swiss art fair with culinary and artistic fare: Jennifer Rubell. From 2002 to 2018, each year on the occasion of the opening week of Art Basel Miami Bech the US concept artist and daughter of famed collector couple Mera and Don Rubell invited everyone to a monumental breakfast in the courtyard of the Rubell Family Collection. Rubell opted for a classic menu: Sometimes there were hard-boiled eggs, croissants, and bacon; other times porridge with raisins; or yoghurt; or Danish pastries, donuts or bread with butter and salt. The way the food was served was anything but conventional. Part installation, part interactive food performance, in “Faith”, 1,573 pastries were balanced on a giant seesaw; in “50 Cakes”, the Rubells spoonfed their guests by hand with chocolate, vanilla, and strawberry cake; at “Just Right”, the public was left completely to its own devices. Borrowing from the fairytale of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, you had to clamber through a hole in the fence into a derelict house, grab a bowl and spoon from two huge heaps, serve yourself porridge from huge, steaming pots, and grab a sachet of sugar, a box of raisins and then get some milk from one of the large fridges.

Rubell, who is also a trained cook, initially rejected the idea of defining her brunch installations as art. However, the participants in the food performances constantly enquired after the name of the artist behind the events and in 2009 the influential art critic at the “New York Times” Roberta Smith labeled a contribution Rubell made to Performa 09 as a “successful melding of installation art, happening and performance”. Only then, and on recognizing how closely her ideas were related to Tiravanija’s concepts and the principles of relational aesthetics did Rubell start to present herself openly as an artist.

Jennifer Rubell, 50 Cakes, 2014, image via journal.the-readymade.com

Jennifer Rubell, 50 Cakes, 2014, image via journal.the-readymade.com

Jennifer Rubell, Incubation, 2011; image via journal.the-readymade.com

While Rubell asked the question whether her work should be classified as hospitality or as an artwork, Tiravanija seems to have gone in exactly the opposite direction. In 2019, for the Institute for Contemporary Art (ICA) in London he designed a sake bar that functions to this day and is attached to the gallery’s café. Equipped with communal tables, paper lamps, and ceramic tableware manufactured in his studio in Chiang Mai, Thailand, initially nothing indicates that the bar is an artwork, and the artist’s name also does not crop up anywhere. People eat, drink, and talk as if in any other normal bar.

Yet once, stepping in someone may have stopped for a moment in front of the small printed card on the wall – “Untitled 2019 (The form of the flower is unknown to the seed)” – and have asked themselves whether this is still art or actually a restaurant, to which Tiravanija would no doubt answer: Who cares? As long as it tastes good!

Rirkrit Tiravanija, Untitled 2019 (the form of the flower is unknown to the seed), 2019; image via pilarcorrias.com