Are artists particulary creative when it comes to cooking? A look into the kitchens of the art world. This time with Christo and Jeanne-Claude, who had their best ideas on an empty stomach.

Being able to live on nothing but air and love would have suited the legendary artist couple Christo and Jeanne-Claude (born on the same day and at the same time in 1935, he in Gabrovo, Bulgaria, and she in Casablanca, Morocco) just fine. The two devoted their entire lives to art – they worked an average of 14 hours a day, seven days a week – and thinking about the next meal seemed like a waste of time to them. Eating was merely a secondary matter, a necessity that had to be dealt with and ticked off as quickly as possible. In the morning, they ate just enough to recharge their batteries for the upcoming workday, then there was usually nothing at all until a late supper.

Christo found the feeling of being constantly hungry quite desirable, because it spurred him on and motivated him to produce outstanding creative achievements and in view of the legendary productivity of the two, the method of culinary abstinence does not seem to have been entirely wrong. In the 50 years that they worked together, Christo and Jeanne-Claude realized dozens of monumental works of art in public spaces, which were preceded by years of negotiation and planning, and financed entirely by the sale of Christo's preliminary drawings and collages. Would the two of them have been able to realize the spectacular wrapping of the Reichstag in 1995 if they had taken a leisurely lunch break every day?

Although the two of them didn't accord food a great deal of space in their everyday lives, culinary matters did at times play an important role in the course of their careers. When they moved from Paris to Manhattan in 1964, it was clear to them that, as newcomers to the New York art scene, they would not get very far without contacts. Without further ado, they decided to phone some important people from the art world – from Marcel Duchamp to Frank Stella to Leo Castelli – and invite them to dinner at their apartment on Howard Street. And they did not consider the fact that neither one of them could cook to be a problem: They simply served their guests a meal of white bread with ketchup and steak from the supermarket on paper plates. In fact, the food was so bad that it remained etched in the memories of those present for years, but thanks to the couple’s charming manner, they still managed to win over an important circle of collectors, gallery owners and art critics.

They served guests white bread with ketchup and steak from the supermarket on paper plates

In the ensuing decades, Jeanne-Claude and Christo would prove time and again that with charm and perseverance they were capable of overcoming even the greatest challenges. For one of their most ambitious projects, “The Umbrellas, Japan-USA” (1991), they planned to erect more than 3,000 oversized umbrellas in rural areas in each of the two countries. Before that, however, they had to obtain the appropriate permission from the respective landowners. They managed to do this with a lot of patience and by drinking an estimated 6,000 cups of green tea offered to them during the six years of negotiations with Japanese rice farmers.

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Umbrellas, Japan-USA, 1984-91, Photo: Wolfgang Volz, image via taschen.com

Christo and Jeanne-Claude, The Umbrellas, Japan-USA, 1984-91, Photo: Wolfgang Volz, image via taschen.com

So Christo and Jeanne-Claude were well aware of the importance of food and drink for establishing personal relationships. When they celebrated their first financial successes with their art, they began inviting friends and acquaintances to dinner not at their home, but at the restaurant of the nearby French Culinary Institute. However, the conversations around the dinner table were largely about their current projects, and this in turn allowed them to move forward with their work even while having dinner with friends.

Christo ate a whole head of garlic every day

Buying time was also important to the artist couple in the long term, which is why they used every available means in an attempt to stay fit and healthy. Convinced that garlic strengthens the immune system, Christo ate a whole head of garlic every day. In the morning he would crush a few cloves and mix them with yogurt and fruit – a habit he put down to his Bulgarian origins – and during the day he would eat the rest on its own, as if it were sweets. He even took the garlic with him on his travels, carefully packed. Until his death at the age of 84, he climbed the 90 steps up to his studio a dozen times a day, where there was not a single chair – he always worked standing.

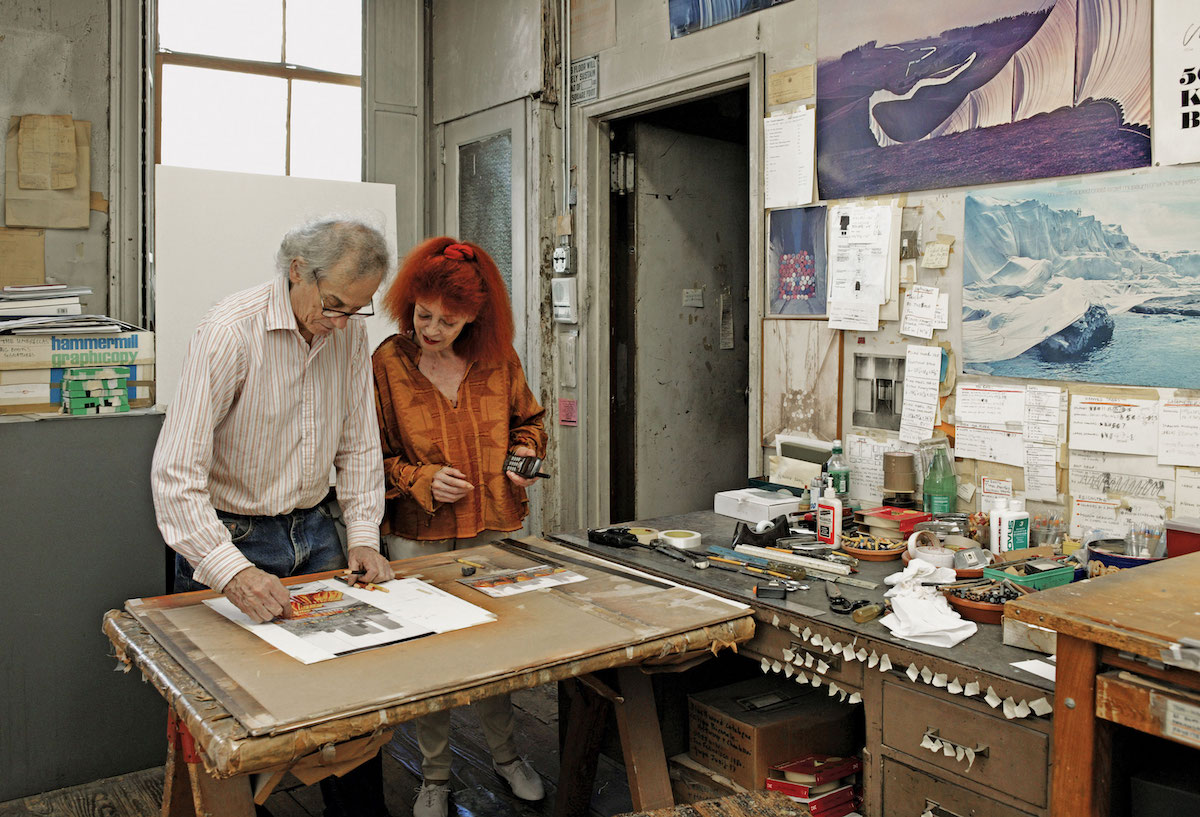

At Christo's & Jeanne-Claude's house, Photo: André Grossman; The Estate of Christo V. Javacheff, image via handelsblatt.com

„Bacon and Egg, Ice Cream and Beef Steak“ (1929) Claes Oldenburg was changing against Christo's work © ArtDigital Studio/Sotheby’s, image via weltkunst.de

Christo and Jeanne-Claude in their house in New York, © ArtDigital Studio/Sotheby’s, image via weltkunst.de

The interior of the five-story former 19th-century factory building in New York's Soho district, where the couple lived from 1964 onwards, hardly changed at all in the 50 years they lived there together. Furnished with homemade furniture and street finds from the time after they moved in, their humble abode gave no indication whatsoever that its owners earned millions by selling collages, sketches, and models. Essentially, the money they earned was plowed straight back into the extremely costly implementation of their ambitious art projects, thereby guaranteeing Christo and Jeanne-Claude both financial and artistic independence. In fact, the most valuable thing the two owned was their art collection: both walls and shelves throughout the apartment were filled with originals by Lucio Fontana, Yves Klein, Marcel Duchamp, Keith Haring, and Nam June Paik to name just a few. But most of these works had not cost them a cent – they had either been gifts from the artists themselves or acquired in exchange for their own works.

There was, however, one notable exception in Christo and Jeanne-Claude's sparse kitchen: two ceramic storage jars perched on top of the refrigerator. At first glance more kitsch than collector's item, they originally belonged to another world-famous artist, namely Andy Warhol, who had a soft spot for cookie jars with curious designs and was a passionate collector of them. Jeanne-Claude acquired the jars in 1988 at the auction of Warhol's estate and paid several thousand dollars for the pair. It is not known why she shelled out such large sum for these two objects of all things. Perhaps she associated them with a special memory, because Christo and she had a long friendship with Warhol.

Christo and Claes exchanged works

Since their arrival in Manhattan Christo and Jeanne-Claude had also been friends with Claes Oldenburg, who along with Warhol is considered one of the best-known representatives of Pop Art. They had met at the famous Chelsea Hotel, which was the epicenter of the New York art scene back in the day and where all three were staying at the same time. Christo and Claes exchanged works at that time, and this is how Christo came to own the sculpture “Bacon and Egg; Ice Cream, and Beef Steak”, which the artist dedicated to him. Shortly afterwards Jeanne-Claude and Christo moved to Howard Street, where they began organizing their infamous dinner parties with prepacked steaks. Perhaps they were inspired by Oldenburg's sculptures, but even if that were the case their guests would no doubt have appreciated the original more.