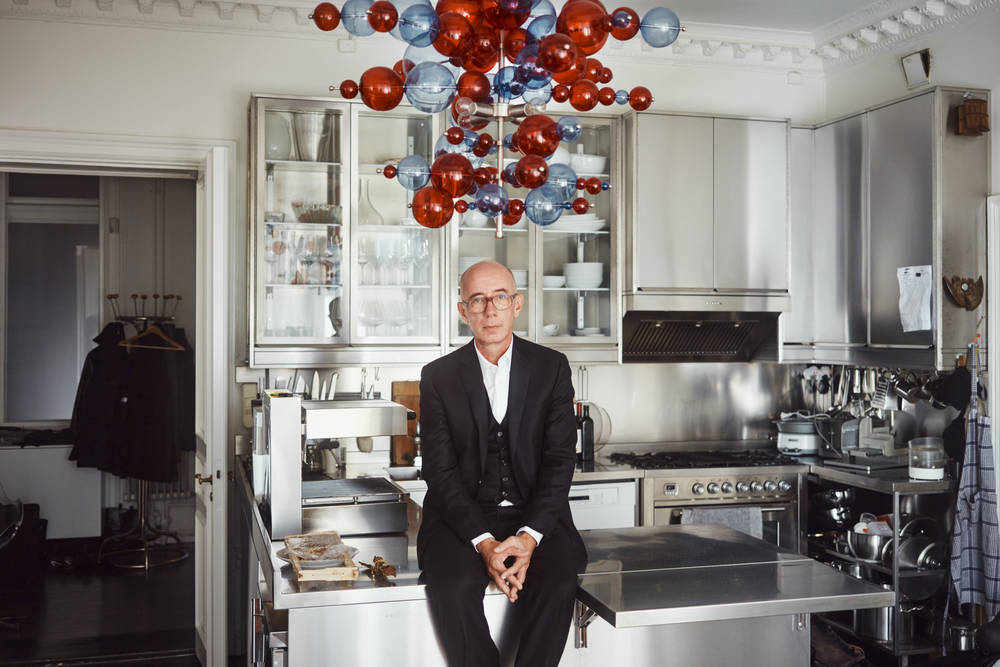

Are artists particularly creative when it comes to cooking? We take a look around the kitchens of the art world, this time with Carsten Höller and his love of brutally simple dishes.

Anyone who orders the “Champignon Carsten” is served a quartered mushroom whose individual parts have been respectively fermented, smoked, steamed, and gently cooked. The result is a culinary pirouette in which a surprising variety of flavors is coaxed out of a single ingredient. The dish can be found on the menu of recently opened “Brutalisten,” a restaurant in Stockholm, and bears the name of the proprietor: Carsten Höller.

Born in Brussels in 1961, the German artist has been working with mushrooms for several decades, although less as a delicacy and more as an artistic subject, and yet there is still a pinch of self-irony in the name “Champignon Carsten”. When Höller installed the “Upside Down Mushroom Room” – a series of oversized, rotating toadstools hanging from the ceiling – at the Fondazione Prada in Milan in 2000, the artist probably had no idea how much the installation would shape his public image. More than 20 years later, visitors to the Fondazione continue to diligently photograph and share the highly photogenic space, cementing the image of “Toadstool Carsten”, even though Höller has consciously never settled on one particular theme or specific formal language throughout his career.

Höller initially studied agricultural sciences, completing a doctorate on olfactory communication between insects, and only came to art late in life. His works have few formal aspects in common, but share the intention to conduct experiments on human perception, where the visitors’ responses become the central part of the artwork: whether in the form of a carousel that only moves at a snail’s pace, a pair of glasses that turns the world upside down, a dizzying tube slide, or a restaurant in which the dishes consist of only a single ingredient that has only come into contact with water and salt.

Behind this restrictive culinary concept is an idea Höller had back in 2018, namely his “Brutalist Kitchen Manifesto”. Back then, he came up with the guidelines for an ultra-purist way of cooking and thinking about food: Instead of creating a new dish by combining several ingredients and adding herbs, spices, and the like, as is usually the case, he advocates potentiating the naturally existing flavor of a single ingredient.

Carsten Höller, Test Site, 2006, (c) Carsten Höller, image via WikiCommons

Carsten Höller, Carousel, image via artreview.com

And behind this idea, in turn, is Höller’s own culinary biography: As a child, he spent summers on the northern part of the Belgian coast, where he used a small landing net to catch gray shrimp which he cooked in seawater and ate – a dish that, in its simplicity and quality, embodies the quintessence of Brutalist cuisine.

Long before the genesis of his manifesto, Höller developed a penchant for seeking out high-quality and sometimes rare ingredients and preparing them as simply as possible. In addition to mushrooms he gathered himself, freshly caught sea creatures, and wild fowl, the refrigerator in his Stockholm apartment sometimes also contains smoked lampreys, Mexican ants, and bone marrow. The artist practically always has frozen insects in stock – although these are not intended for his own palate but for the two dozen rare songbirds he keeps as pets.

Birds have always fascinated Höller; as a schoolboy, he voluntarily got up early on Saturdays to take part in a bird ringing program. Today, he breeds songbirds from all over Europe in his Stockholm apartment; even the guest bedroom had to be given over to the spacious cages. Höller observes the development of the animals over years and documents it meticulously; for him, the birds are both pets and objects of study.

Nevertheless, Höller feels no inhibitions about eating the animals – wild birds are among his favorite foods. In order to enjoy the protected species that is the ortolan – a songbird considered a delicacy in France, where it is first fattened, then immersed in Armagnac and then eaten with a cloth napkin over one’s head to capture as many flavors as possible – the artist decided to breed the rare bird species at home. But when the chicks were finally born, he couldn't bring himself to eat them. He only got to enjoy the delicacy when a female fell victim to a male.

The first idea for the Brutalist manifesto came to Höller, fittingly enough, when he was eating a bird dish in Ferran Adrià’s legendary restaurant “El Bulli”. There he was served the brain of a woodcock, embedded in its own skull –a simple and perfectly executed dish that also used parts of the bird that usually end up in the trash. This experience was instrumental in the concept of Brutalist cuisine, which advocates putting as many components of one ingredient, whether animal or vegetable, on the plate as possible.

What the practical implementation of this theory looks like on the plate can be observed in Höller’s restaurant, for example, with the “Guinea fowl à la Brutalisten”: The bird’s leg complete with claw is prepared as a confit, while the breast and heart are grilled, and a mousse prepared from egg, liver, meat, and skin. Careful dissection into individual parts makes the basic ingredient appear in a new light; the (new) whole is more than the sum of its parts. The same applies to “Champignon Carsten” and his many facets as artist, scientist, ornithologist, and gourmand.