Cultivating coexistence. That’s what this year’s Manifesta 12 in Palermo calls for. In churches, gardens and palaces, the exhibited works raise questions about pressing issues like migration and climate change.

Hedwig Fijen, Director of this year’s Manifesta 12 in Palermo, opened the itinerant European Biennale for contemporary art and culture by saying that the Sicilian capital is a “microcosm of concentrated history.” Indeed, there are only a few cities in which the traces of the past and the challenges of the present are as evident as they are in Palermo, incidentally also Italy’s Capital of Culture this year. In its time it has been home to Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Normans, Staufers, Angevins, Aragonese, Spaniards, Savoyards, Austrians, Bourbons and ultimately the Italians.

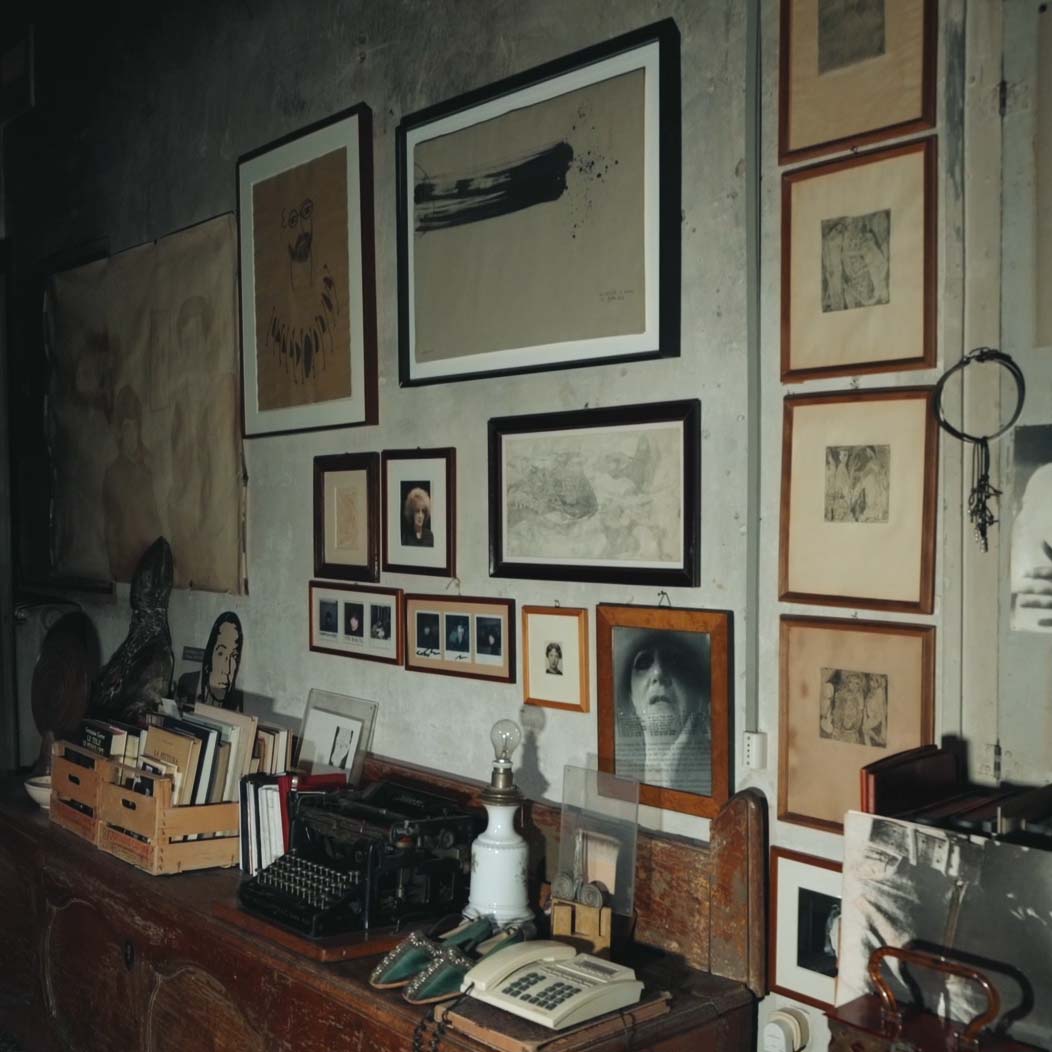

Works by 50 artists, including 35 commissioned works, are on show at 20 historical locations, among them churches, gardens and palaces, none of which are art institutions and many of which are ordinarily closed to the public. With its leitmotif “The Planetary Garden. Cultivating Coexistence,” Manifesta 12 refers to the impact of migration and climate change and asks whether art can influence the future of a city, a region and a society.

Dreaming of a harmonious coexistence

The “icon” of Manifesta 12 is the painting “View of Palermo” (1875) by Francesco Lojacono, Sicily’s renowned 19th-century landscape painter, belonging to the local Galleria communale d’Arte Moderna. Indeed, there is nothing indigenous in this historical representation of the city. Rather, it shows the successful outcome of integrating non-native species: The olive trees depicted are from Asia, the prickly pears from Mexico, the medlar trees from Japan, and even the lemons – the symbol of Sicily – are a legacy of Arab rule. Thus the nomadic biennial focuses on the ambitious notion of a planetary garden and explores the potential for harmonious coexistence. “Here in Palermo,” says Mayor Leoluca Orlando, “there are no migrants, because those arriving in the city become Palermitanos.”

Francesco Lojacono, Veduta di Palermo, 1875, Image via www.gampalermo.it

The central locations of the traveling exhibition are within walking distance in the Old Town quarter of La Kalsa. Its heart is Piazza Magione, which can be read as a symbol of the city. After the Allied bombing raids, actually directed at the port, destroyed the old palazzi in 1943, a huge wasteland was left behind. The restitution payments made after the War were embezzled and the piazza deteriorated into a parking lot. Those who could afford it moved away from La Kalsa to the outskirts of the city. In the immediate vicinity is S. Maria dello Spasimo, a church that lost its roof: a magical place with an elevated garden that affords a wonderful view of the surrounding hills. It is here that an installation by London-based Cooking Sections is situated. The artist collective founded in 2013 based its installation on Sicily’s traditional irrigation systems.

The bienial consists of the three sections “Garden of Flows,” “Out of Control Room” and “City on Stage.” “Garden of Flows,” following the official press release, “explores the concept of toxicity, the life of plants, and the culture of gardening in relation to the resources of the planet and the global common good. Out of Control Room seeks to make the invisible networks of digital flows tangible. City on Stage encompasses the stratified nature of Palermo in an attempt to foster a critical understanding of various aspects of the city’s contemporary life.” All this sounds highly ambitious and very text-heavy.

A rotting industrial plant in the heart of the botanical garden

In addition to Lojacono’s painting it was the Orto Botanico (the University of Palermo’s Botanical Gardens, established in 1789), that provided key inspiration for the concept of the four curators. This is where artist Michael Wang, born in 1981 in Onley, USA, has positioned a staircase by a wall that affords a view of an old Moreton Bay fig tree on one side and a derelict industrial plant on the other, thus underlining human intervention in our ecosystem. The Botanical Gardens are also host to a video by Hong Kong-based artist Zheng Bo, who was born in Beijing in 1974. The work shows seven young men in a forest in Taiwan in intimate contact with plants, which the artist terms “Pteridophilia,” roughly translating as “love of ferns.”

To the north of the Orto Botanico we find Palazzo Forcella De Seta. Originally a vacation home belonging to a noble family, it was destroyed during the 1820 revolt and then completely renewed. In 1933 it was purchased by Enrico Forcella, Marquis of Villalonga, who had it converted, for instance with an Alhambra hall, in which Dutch artist Patricia Kaersenhout (born in 1966) has deposited a large mound of salt. In the accompanying video we hear about a Caribbean story that tells of how slaves didn’t eat any salt in the belief that this would make them lighter and enable them to fly back to Africa. With her work Kaersenhout invites visitors to take some salt, pour it into water and in so doing symbolically dissolve the pain of the past; salt as an element of the sea, across which people have been displaced but also head off in the hope of starting a better life.

Walking from one palace to another

Further north again is Palazzo Butera, which shields the Old Town from the Bay of Naples. The impressive baroque palace is currently undergoing meticulous restoration after years of neglect. It was purchased by collectors Francesca and Massimo Valsecchi in 2015 and is now part of the first section of the biennial, the “Garden of Flows”. Renato Leotta, who was born in Turin in 1982 and divides his time between Lisbon and Italy, presents an installation here made of terracotta tiles which show depressions that look like ripe lemons had fallen from a tree.

With this piece Leotta wishes to show that time and place are connected through gravity. Melanie Bonaja (the Dutch artist born in 1978 had a solo show at Frankfurter Kunstverein in 2017) is showing a three-part video on the sense of alienation to nature felt by many people living in the West. The artist group Fallen Fruit, in turn, founded in Los Angeles in 2004, has hung in a room with a sea view photographic wallpaper showing the fruits that grow throughout the year in the public gardens of Palermo: mandarins, grapefruits, oranges, kumquats, tangelos and avocados in January and February, blood oranges, medlars, mulberries and guavas in March and April, and so on, through to the end of the year.

A wallpaper with fruits that grow in Palermo all year round

Heading back into the city you will reach Piazza S. Francesco d’Assisi, where you can eat the famous spleen sandwiches followed by at least one dolce before proceeding to Oratorio di San Lorenzo. The small Oratory of St. Lawrence, which was recently extensively restored, is part of the third section, where the city itself plays a central role. The sound recording of a performance by Nora Turato (born in 1991 in Zagreb), who is concerned with the history of women in Sicily, enables visitors to take their time viewing the lavish stuccowork by Giacomo Serpotta (1699-1706). The painting of Christ’s birth at the altar is a copy, however. The original by Caravaggio (1608) was stolen back in 1969. A recently published book by Rossana Dongarrà on this sensational robbery is cause for hope that the painting still exists.

Good walkers can now continue their way (three hours on foot or 30 minutes by taxi plus one hour on foot) northwards to Pizzo Sella, at 562 meters the highest point of Monte Gallo, which separates Palermo from its suburbs Mondello and Sferracavallo in the northwest. Although protected under nature conservation regulations, a settlement was built here between 1978 and 1983, which became a symbol of corruption. The concrete ruins are an example of the “Incompiuto Siciliano” or “unfinished Sicilian” style, for the Cosa Nostra earned its money not from finishing buildings but from the building work itself. Yet Palermo stands by its history and hopes that this culture, in the context of which the Palermo Atlas was also developed, will stimulate sustainable urban development. The view from up here at least makes every single step worth it.

The US Navy in the cork forests of Sicily

The 15th-century Palazzo Ajutamicristo is located less than five minutes south of Oratorio di San Lorenzo. The nine works on show here, all of which are part of the first section, the “Garden of Flows”, include one by Tania Bruguera, who was born in 1968 in Havana, where she still lives and works. Bruguera examines the new satellite communications system used by the US Navy. One of its four ground stations worldwide is to be found in one of the last cork forests in Sicily, close to the town of Niscemi, and enables remote-controlled warfare to be waged.

It is not data transmission and radio waves, but migratory and goods flows that Lydia Ourahmane addresses in her installation “The Third Choir”. It consists of 20 empty oil barrels each with a cell phone inside, all of which emit the same radio station. The piece by the artist, who was born in 1992 in Saïda, Algeria, constituted her final project at the London Academy in 2014 and is the first work of art to leave Algeria legally since 1962. Ourahmane reflects on the sheer red tape involved in the work’s journey from Algeria to Europe, in the same direction in which so many want to travel who embark on the dangerous journey across the Mediterranean Sea.

At the beginning of Manifesta 12 Marinella Senatore organized a procession (documentation is available in Chiesa dei SS. Euno e Giuliano on Piazza Magione). The “Protest Bike” by the artist, who was born in 1977 in Campania and lives in Paris and London, was recently on show in the SCHIRN exhibition “Power to the People.” For her three-hour “Palermo Procession” Senatore motivated numerous locals – four dance groups, a band of drummers, one Rock and one opera singer, a church choir, two ensembles, a group of supporters, a martial arts club, a choir for the deaf and mute, and several school classes – to present Palermo as a city of dance, a city in constant motion. The procession started at Fontana Pretoria, which owing to its numerous nude statues is colloquially known as the fountain of shame, and ended at the sea – at precisely the spot where the bay is so beautiful that it is also called La Conca d’Oro, the Golden Shell.