For decades, Mark Dion has created a collection of miraculous finds. We were allowed to enter his home cabinet of curiosities and made all sorts of discoveries.

Dion comes back with a steaming cup of tea in a thin, vintage china pot with an intricate burnt orange flower pattern on it. When I complement him on his assemblage and want to know, what makes an item interesting for him, he smiles almost coy: “Well, you know I think that there are background objects that can be less specific and are more about creating a scene or creating ambiance, and then there are foreground objects that have to take on the burden of meaning.

Imagine you fill a book shelf with books, but there is only one book, that you put on the desk, that book takes on a different kind of weight. I like the theatricality of installations. I like to imagine my audience as detectives and I've set up the crime scene. And that's how meaning is generated.” Since he doesn’t have a formal studio a lot of the objects he uses in his installations eventually migrate through his apartment, his personal space. But, where one would feel sad about letting beloved items go, Dion feels differently: “Well, there are things, that I really like and that I'm drawn to because they have a beautiful formal quality or they have that specific patina of use, but they are not necessary things I need to keep. I feel like putting them in an installation is the best of both worlds. Because in some way I get to keep them, they will always be part of me, associated with me, but I actually don't have the burden of owning them and taking care of them.”

Behind the stacks of books peeps the face of a possum

He jumps out of his chair and makes a bee line for the large book piles, towering on top of the glass vitrines in the hallway and starts searching frantically. “Where is it? Somewhere in here I have this edition of the book, the only book that was in the household that I can remember. Ah there is it!”

He pulls out a worn and torn paperback, right next to the face of an opossum, peaking out behind the stacks. “This is ‘A Golden Guide: Seashores.’ I grew up on the sea, and this was the only book that we had. The most important thing I found in this book was the idea that this stuff is knowable. You didn't have to go to the beach and have all this be just confusing jumbo. You can actually look up the proper names of these organisms and learn about their life cycles and what they do.”

Nature and its conservation have long been the subject of Mark Dion‘s work

Warming up to the idea of sharing his favorite objects, he opens the vitrine and pulls out a pack of vintage flash cards with animal motifs on it. “These are for bird identification. Aren't they great?! I think of them as my most prized possessions, especially these with the prehistoric animals, because like all kids I was a dinosaur freak.”

His cheeks are glowing as he rushes over into the living room to another vitrine to look for more treasures. As he crosses over he stops dead at the couch on which the dog made herself comfortable. “Hera, you look a bit chilly, I think you need a blanket.” He takes the off-white wool blanket from the arm rest and folds it around the slightly shivering dog who snuggles her head right into it. “She’s a whippet and this is how she spends most of her day.” Leaving Hera to her nap, we move on to the next object of interest: a 3D-print of a fish.

It’s a small model of one of his recent projects, a public sculpture in Stavoren, Netherlands. Now completely in his element he walks me through the whole process of how this piece came about. From his first red and blue sketches – he mostly sketches projects in red and blue crayons – over a computer model, to a 3D printed version, to the final massive fish fountain positioned in the center of town.

“You know the public was not so crazy about this. They were like ‘Uh this is like Disney Land, you're bringing your American imperial Disney sensibility to Holland.’ And I said ‘Trust me.’ And of course now everybody loves it, but you have to go through this process. It’s a lot of negotiation. Nature and the discourse of how we try to preserve it, has been a part of Mark Dion’s work for a long time.

One of his famous pieces “Mobile Wilderness Unit” is part of the “Wilderness” exhibition at SCHIRN until February 2019. It is composed of a stuffed wolf, standing on an open trailer decorated with materials representing the wolf’s natural habitat like twigs and grass. “You know the term wilderness is really problematic, right. It’s one of the terms that people in conservation, in land protection argue, think, and write about. There is this famous William Cronon piece, ‘The Trouble with Wilderness’, which is a central piece for thinking about these ideas. We’re living in times where cities are consolidating the population, the countryside is de-populating.

Those of us who are interested in protecting wild things and places know if people don't have contact with them they will never fight for them. If you don't know an elephant, or see an elephant in his place why would you care if elephants are protected or not. This causes kind of a conundrum – and there is no real solution to this: Do we take people out of the city to the wilderness? Do we take the wilderness to people?

So, this piece is in a humorous way engaging that sort of dialogue, that one could pull this wagon about and introduce people to a wolf in its natural habitat. It’s a little bit of a critique of the idea that to just introduce people to the wild is going to be enough to make them care. Like all of my work it’s quite melancholy, but tempers that with humor.” Does he think that wilderness is a topic that will play a role in art projects in the future?

They were like ‘Uh this is like Disney Land, you're bringing your American imperial Disney sensibility to Holland.’ And I said ‘Trust me.’

He pauses and thinks for a while. He finally sighs: “I think there will always be a kind of attraction, a romantic notion of wilderness. I don't know if that is more harmful in terms of being able to negotiate what’s really important about conservation in the future. I think wild places are important to keep, because we need the blueprint of what was here before. And as a society we can afford to do it. We really don't need to chop the last ones. We don't really need to develop the last wild places on earth.”

Every cabinet of curiosities needs a crocodile

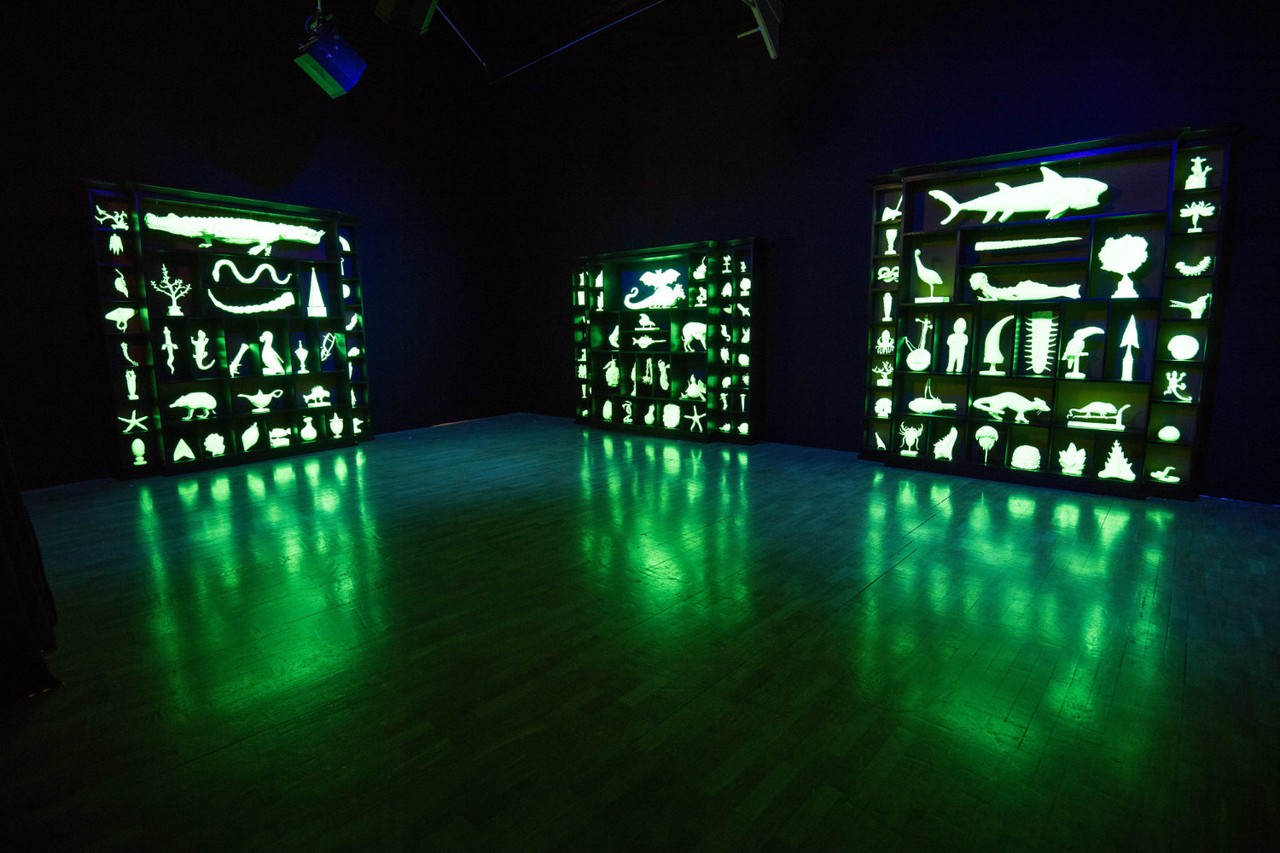

Dion’s work has always been critical not only of how we choose to present nature, but also how we choose to preserve it. And he enjoys a dialogue with the public about these and other questions, working for various public art projects himself. His latest piece, “Cabinet of Wonder,” is a large cabinet of curiosities completely designed and filled with life by Dion for the “Gathering Place”, a public park and art program in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Mark Dion, The Library for the Birds of London (Detail), 2018, Image via artmap.com

Mark Dion, The Wonder Workshop, 2015, Foto: Jeff Spicer/PA Wire, Image via artmap.com

It’s a one of a kind project, that gave the artist carte blanche to do whatever he deems best. And though that might be a nice idea in theory, Dion says, that “the audience in Tulsa is not the audience in New York City. The whole park is really designed for children.” That’s why he wanted to make a space like the fish fountain in Stavoren “where the emphasis is on delight and wonder, rather than analysis and criticism.” And where there is, of course, a crocodile hanging from the ceiling, because: “Every cabinet needs a crocodile.”

Mark Dion, Cabinet of Wonder, 2018, Image via tulsaworld.com