Rarely are movements in art so hard to describe: Dadaism is not just about fooling with and confusing the public, but also about political protest.

“Dada shows the world in 1920. Many will say: Even 1920 is not so horrible. This is how it is: The human being is a machine, culture is in shreds, education is arrogance, spirit is brutality, stupidity is the norm and the military is sovereign”, wrote Adolf Behne on the occasion of the “First International Dada Fair”, which took place in the summer of 1920 at the Berlin gallery belonging to Otto Burchard. Yet at this point the Dada movement was already trundling towards its own grave.

It all began in Zurich in 1916. Hugo Ball founded the “Cabaret Voltaire” and brought various artists on board who had likewise gone into exile in neutral Switzerland during World War I. When he took to the stage in his famous costume made of stiff cardboard, which drastically limited his ability to move his body, he was aiming criticism squarely at society: at the rigidity of the Wilhelmine empire, which entrenched itself behind the monocle and upturned collar and the omnipresent “sexual angst”. Sound poems read by multiple people simultaneously, which sounded like an all-encompassing stutter, typified the hum in the trenches and the senseless murder on the battlefields.

Hugo Ball performing at Cabaret Voltaire in 1916, IMAGE VIA: WIKIMEDIA

Yet while the group in Zurich levied their criticism in a roundabout way, the Berlin group did not mince its words. “We will blow Weimar apart. Berlin is the place of Dada. Nobody and nothing will be spared”, it states on the flyer “Dadaists against Weimar” from 1920. Richard Huelsenbeck had brought the ideas of the movement from Zurich in 1918 along with a “Dadaist Manifesto”, and in Raoul Hausmann, John Heartfield, Johannes Baader, George Grosz and Hannah Höch he quickly found allies for “Club Dada”.

Bloody Earnest

Their dislike of the Weimar government, Prussian bureaucracy and the wanton double-morals of the bourgeoisie was expressed in countless manifestos, pamphlets and invocations; in-house publications such as “Der Dada” [“Dada”] by Raoul Hausmann, “Der blutige Ernst” [“Bloody Earnest”] or “Jedermann sein eigner Fussball” [“Everyman his own football”] may have appeared only rarely, but they caught the attention of the local press and, of course, provoked the bourgeoisie.

Hannah Höch and Raoul Hausmann in front of their works at the “International Dada Fair“, on the left Höch's work “Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany” from 1919, Berlin 1920; Berlinische Galerie; © Berlinische Galerie / photo: Kai-Annett Becker / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2016, Image Via Kulturstiftung der Länder

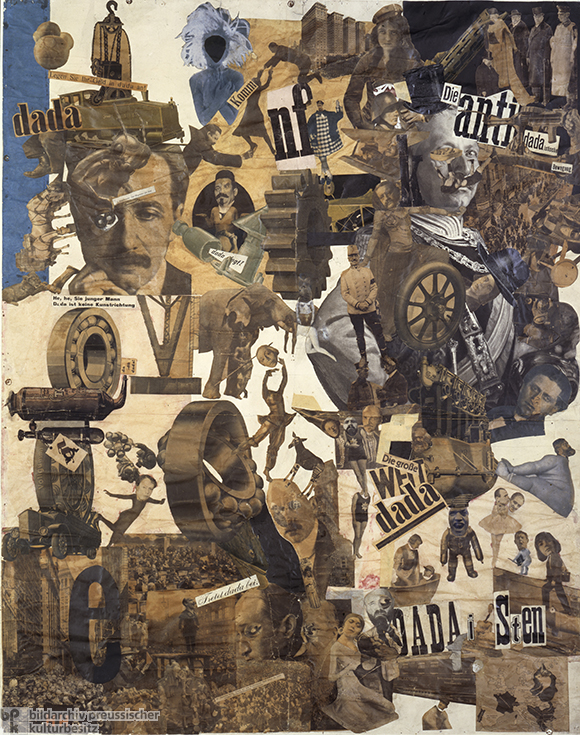

Hannah Höch’s collage “Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser Dada durch die letzte Weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands” [“Cut with the Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany”] is made up of photographs and magazines – a new form of presentation at the time. With it she fittingly dissected the society of the day and thus contributed to the formation of a new type of artist. “In this excellent climate, in this blunt destruction, one cannot be a good old type of conventional artist. So en avant DADA! Even the cautious DADA, the indecisive fumbling from Zurich is no longer good enough, to hell with it!”, Raoul Hausmann wrote later in his autobiography, remembering the attitude to life at that time.

Dada against everything

Although there were no written rules among the groups of Dadaists that formed not only in Zurich and Berlin, but also in Cologne and Hanover, the protagonists collaborated to a greater or lesser extent: “Since Dada is the most direct and liveliest expression of its time, it is against everything it finds obsolete, mummy-like, stuck”, it states in Richard Huelsenbeck’s “Dada Almanach”.

Hannah Höch, Cut with the Dada Kitchen Knife through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany (1919), Original: Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen, Berlin, Germany, © Bildarchiv Preußischer Kulturbesitz / Nationalgalerie, SMB / Jörg P. Anders, Image Via DGDB

At the same time, they propagated a provocative denial of sense, often leaving unanswered the question of what was intended with their poems, performances and collages. Dadaism, as George Grosz described it once, “arose as a reaction to the cloud-wandering tendencies of the so-called sacred art, which found meaning in cubes and gothic, while the field commanders painted in blood” – and, indeed, as a counter-movement to the representatives of Expressionism, which saw World War I as a necessary purification of humanity.

Dada died a sudden death

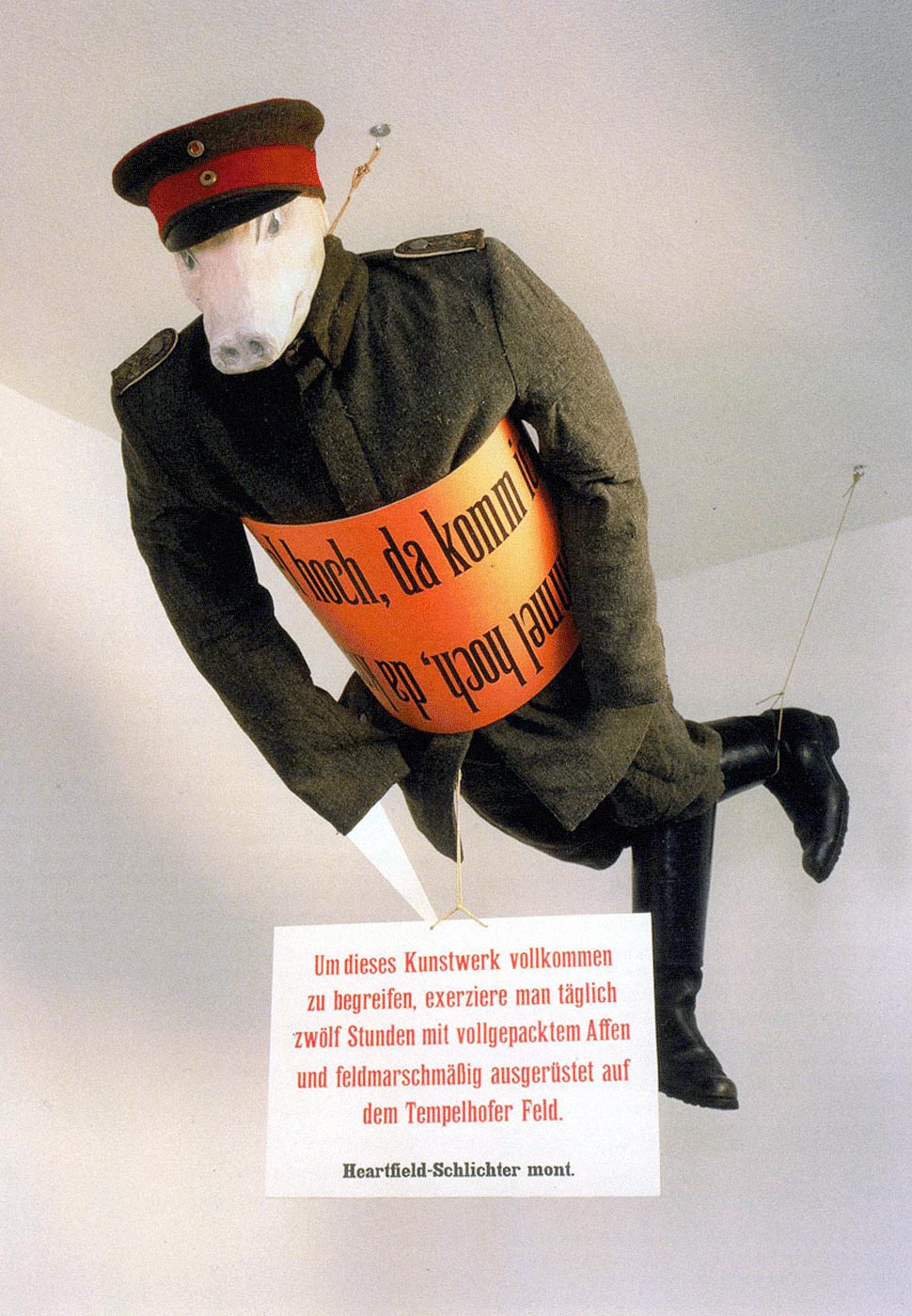

With the beginning of the Weimar Republic, the Dada movement did not come to an end, but it was increasingly watered down and began to lose its provocation. The Dada Fair of 1920 appeared to be the group’s last gasp, but it resonated little with the public. Only a charge brought by the Reich Ministry of Defense against George Grosz, John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter – the latter had placed a pig’s head on top of a soldier’s uniform for the sculpture “Prussian Archangel” – created something of a temporary storm. Yet during the trial the defendants claimed they were “only having fun” – and thus betrayed themselves and the entire movement. “DADA was dead, without glory and without a state funeral. Simply dead”, summarized Raoul Hausmann later.

Reconstruction of "Prussian Archangel", John Heartfield and Rudolf Schlichter 1920, for the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Image via WERKSTATT FÜR UNBESCHAFFBARES

Yet the concept of Dada lives on today in one way or another: in contemporary performance art, in the sensory, confusing sculptures by visual artist John Bock, for example, and in the experimental lyrics of one Ernst Jandl, even if these relate less to criticism of global war and more to the redefinition of artistic forms of expression. Dada is dead? Long live Dada!