The first free and democratic elections took place in Germany just under 100 years ago and marked the dawn of what then became known as the Weimar Republic. Comments on a young democracy that was knocked off its unsteady feet by radical nationalists.

When the exhibition “Splendor and Misery in the Weimar Republic opens on October 27, the newly elected government of the Federal Republic of Germany will hopefully have formed itself. The fact that 61.5 of around 82 million people are able to cast a free vote may be a matter of course to us today. Yet the first free and democratic vote took place less than 100 years ago.

On January 19, 1919 Germany voted for its first national assembly in the newly founded Weimar Republic. Parliament in the inter-War years never had it easy. It suffered under the legacy of the Treaty of Versailles (see article Peace Agreements), had to hold its ground against attacks from the far left and far right, and try to make parliamentary democracy palatable to an older generation of monarchists. To this day, the decision-makers during the inter-War years continue often to be accused of having failed completely – in particular with a view to the rapid rise of the Nazi party. But this verdict does not do them justice.

Top-down revolution

In light of current events, this article casts a glance at the first free votes in Germany in 1919 and places them in a historical context. How did a monarchy become a democracy? What was the context in which the first German democracy evolved and why did it only last a few years before disintegrating? Since the AfD has turned from a Euro-skeptical party (in 2015) into a right-wing populist one, comparisons of today’s situation to the inter-War years already abound. What parallels really do exist and what is different today?

Shortly before the proclamation of the republic: the SPD politician Philipp Scheidemann speaks from a window of the Reichskanzlei to the people, 9th November 1918, Image via Wikimedia Commons

September 1918. The German Reich, a constitutional monarchy under Wilhelm II, was in the last throes of World War I and close to the point of both military and economic collapse. As the situation seemed likely to deteriorate at the time and in order to prevent a “top-up revolution”, as had just been observed in Russia in 1917, a “top-down revolution” was decided upon. The Reich administration, appointed by the Kaiser, was deposed, and a Reich government supported by parliament was introduced on October 3, 1918.

Insubordination and rebellion

Prince Maximilian of Baden, one of the Kaiser’s cousins, was made Chancellor of the German Reich. With the government established, offers of a ceasefire were made to the Allies. While the German people were surprised by these offers – for years they had been advised by Reich propaganda that peace could only be brought about by a victory – they quickly accepted the turn. In fact they did so faster than the government of the Reich would have liked. At the end of October 1918, people were already broadly calling for the Kaiser’s abdication, in particular as the latter, along with the high-ranking military men, showed the new government no loyalty.

Berlin: Charity of poor people by the Protestant church community, Image via commons.wikimedia.org

The civilians went out on the streets to protest, while on the military side the sailors began to mutiny against the authorities. After the war had already been lost, the German High Seas Fleet wanted to sail for a last blow against the Brits in spite of the offers of a ceasefire. But the sailors rejected the command, and starting with the sailors from Kiel at the beginning of November, a revolutionary mood spread ´through the Reich. Soldiers’ and worker’s councils were founded in the cities in order to express their demands. In their minds, the old order already belonged to the past. But the emperor still sat on his throne and refused to budge.

Unreservedly pro-democracy

Prince Maximilian therefore saw himself forced to declare the Kaiser’s abdication himself, and Reich Chancellor Friedrich Ebert addressed the people, promising a vote for a national assembly. Women were also to be allowed to vote for the first time. Yet this was not enough for the demonstrating masses in Berlin, such that on November 9, 1918 around 2 p.m., the Social Democratic politician Philip Scheidemann saw himself compelled to speak to the people from a balcony of the Reichstag. In doing so, he not only announced the Kaiser’s abdication, but let himself be carried away to proclaim Germany a republic.

On the Reichstag election on 4 May 1924. The German Chancellor, Marx, gives his vote, Image via commons.wikimedia.org

The first free and democratic vote after the end of the monarchy took place on January 19, 1919. What was new was not just that women were given the vote, but also that the voting age was lowered from 25 to 20. Of all of the votes, 70% went to the parties SPD (who were to put up the first President of the Reichstag in the person of Friedrich Ebert), the Catholic Centre Party (which later on was to merge into the CDU for the main part) and the center-left German Democratic Party. All three parties were fully committed to democracy. However, they had already lost their majority forever when it came to the vote for the first Reichstag one year later.

Repression and intimidation

Today, the inter-War years are known for the instability and short-lived nature of the governments. In principle, the Reichstag was elected for four years at a time, yet the vote was always brought forward in order to achieve a clear majority. After the election of the first Reichstag in 1920, two votes were held in 1924, then Germans voted again in 1928, 1930 and twice again in 1932. The President of the Reich was elected by the people directly. He then in turn appointed the Reich Chancellor, who held far-reaching powers, including the right to dissolve the Reichstag and the ability to declare a state of emergency in those cases were public safety was under threat.

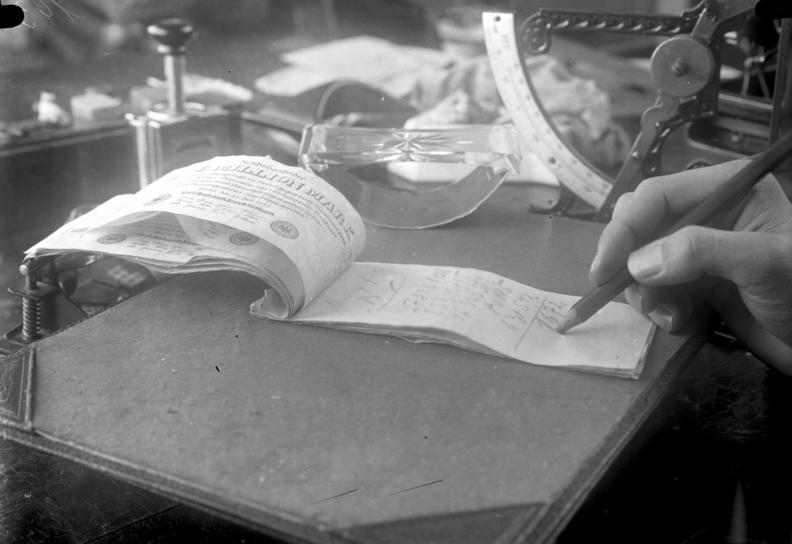

A million-mark as an accounting block. Image via commons.wikimedia.org

Adolf Hitler was later to make use of these two powers. The Nazi party first stood for election in 1928, when it only gained 2.6%. At the elections two years later the party already reached 18.3%, and over 30% at both elections held in 1932. The election held on November 6, 1932 was to be the last free democratic vote for many years, as the election held in March 1933 already took place under Nazi repression and intimidation and can only be partially classified as democratic. President of the Reich Paul von Hindenburg finally appointed Adolf Hitler Chancellor of the Reich on January 30, 1933, putting the nail in the coffin of the young republic.

Dusk of democracy

To this day, the question remains both fascinating and alarming: How was the Nazi party able to rise to power so rapidly? The people’s insecurity and impoverishment, resulting from the global economic crisis, played a central role. The public desired a strong leadership personality – either because they were used to having one in the monarchy or because such a figure was lacking in the broad party spectrum of the republic – and the Nazi party distinguished itself exactly by this factor. In addition, it intentionally staged scenes of civil war in order to then appear as a protective power.

Adolf Hitler in 1933, Image via commons.wikimedia.org

At the same time the democratic parties were very much rooted in their milieus and their focus was quite inflexible and unwilling to compromise. In this context there is often talk of a failure of democracy, yet what is seldom taken into account is that German democracy in the Weimar Republic was only just learning to walk and not yet sure-footed. The historian Tim B. Müller emphasizes an interesting aspect in relation to this in a contribution to weekly newspaper ZEIT: At the time there simply were no role models and traditions that could have been called upon. Few countries saw themselves as democracies before 1918, in the US for example democracy simply stood for the politics of the Democratic Party. A clear definition of the term “democracy” was fundamentally lacking.

The right motivation

With the rise of the AfD in recent years, comparisons to the Weimar Republic have been drawn time and again. It was the first time since 1932 that a right-wing populist party was able to achieve double-digit election results in state elections, and prognoses for the parliamentary elections point to similar results. Like the Nazi party, the AfD has become radicalized over a longer period of time. But are the motivations for voting for a populist-nationalist party the same today as they were then? This remains a highly complex question, one that is almost impossible to analyze at this point. While the longing for a strong leader played a role in the inter-War years, the attraction of populist parties – whether in Germany, France or the US – now seems mainly founded in wanting to exact revenge on the political establishment. It remains questionable whether that is the right motivation in deciding on whom to vote for.

The constitutional ceremony in Berlin on August 11, 1923. Image via commons.wikimedia.org

Non-human living sculptures by Hans Haacke and Pierre Huyghe

In his early work, HANS HAACKE already integrated animals and plants as co-actors into his art. In that way he not only laid the foundations for a...

CURATOR TALK. CAROL RAMA

SCHIRN curator Martina Weinhart talks to Christina Mundici, director of the Carol Rama Archive in Turin, editor of the first Catalogue Raisonné and...

Freedom costs peanuts

HANS HAACKE responded immediately in 1990 to the fall of the Berlin Wall and turned a watchtower into art.

The film to the exhibition: CAROL RAMA. A REBEL OF MODERNITY

Radical, inventive, modern: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN provides insights into CAROL RAMA's work.

Now at the SCHIRN: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: the SCHIRN presents the groundbreaking work of the compelling...

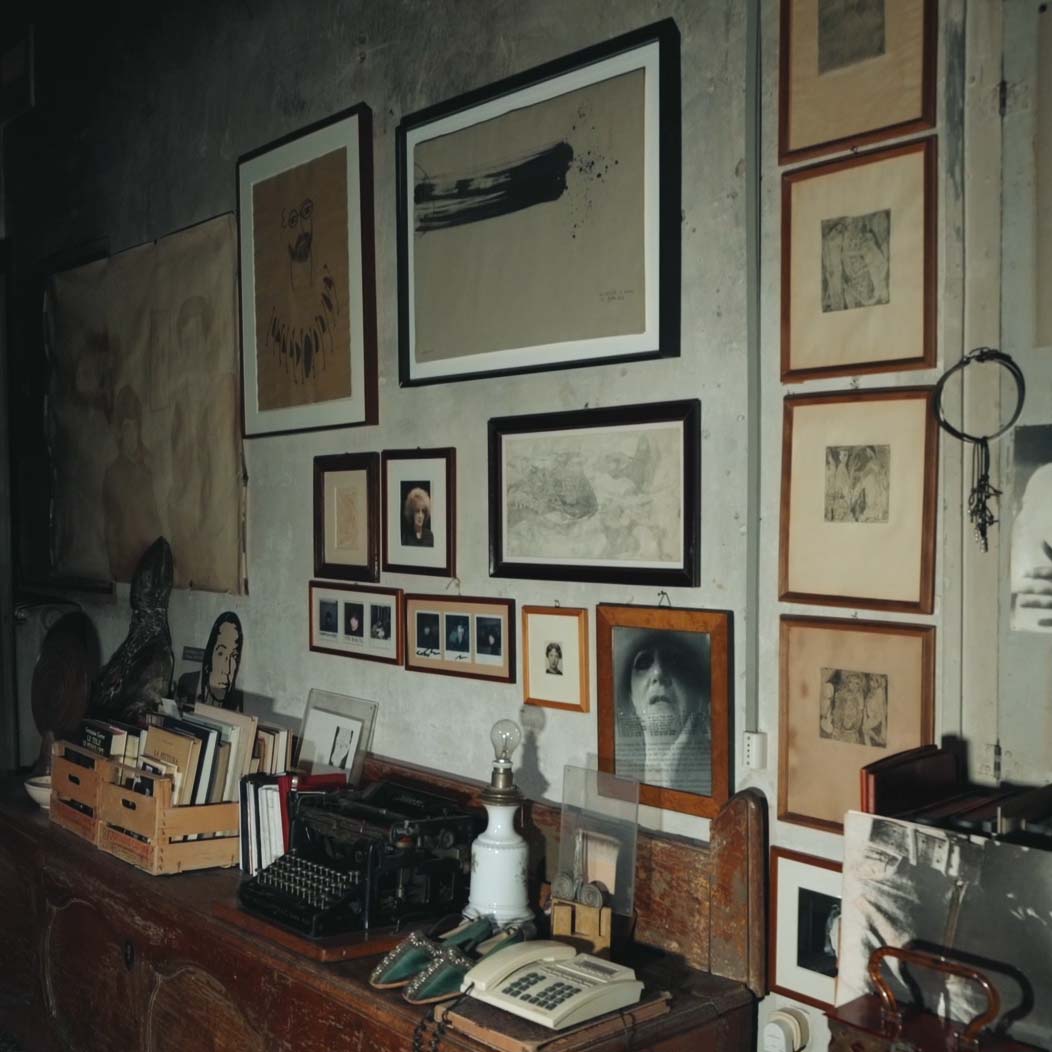

Carol Rama’s Studio: A nucleus of creativity

CAROL RAMA determinedly forged her own path through the art world. Her spectacularly staged studio in Turin was opened to the public only a few years...

PANEL: POLITICAL ACTIVISM BY SELMA SELMAN

Hosted by Arnisa Zeqo, Amila Ramović and Zippora Elders speak with the artist Selma Selman about her artistic career, the exhibition SELMA SELMAN....

Now at the SCHIRN: Carol Rama. A rebel of Modernity

Radical, inventive, modern: the SCHIRN is presenting a major survey exhibition of CAROL RAMA’s work for the first time in Germany.

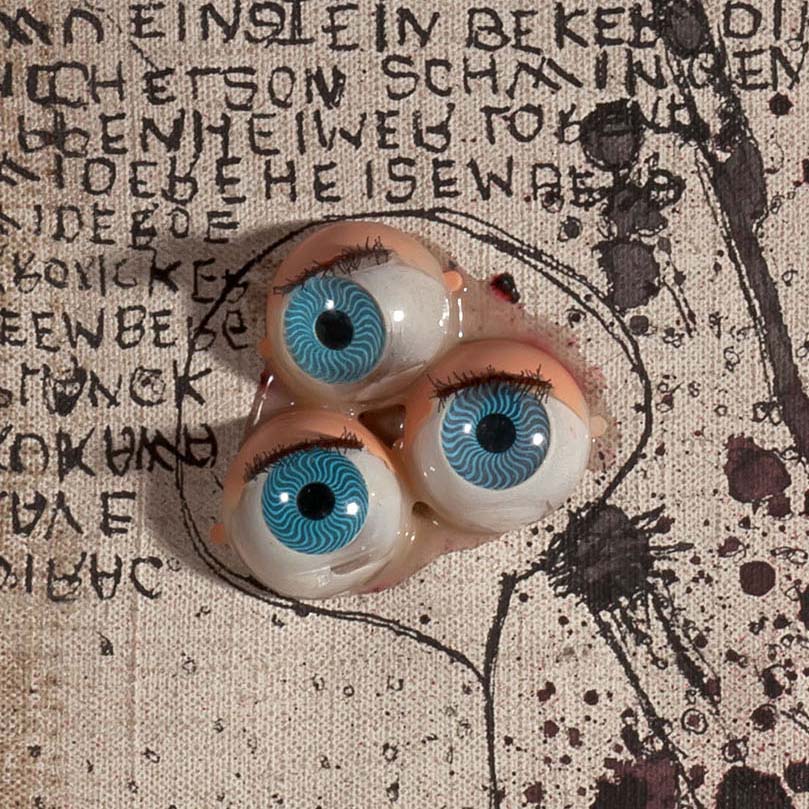

Carol Rama in 10 (F)Acts

CAROL RAMA was one of the most provocative female artists of the 20th century. With her explicit depictions of sexuality, physicality, and tabooed...

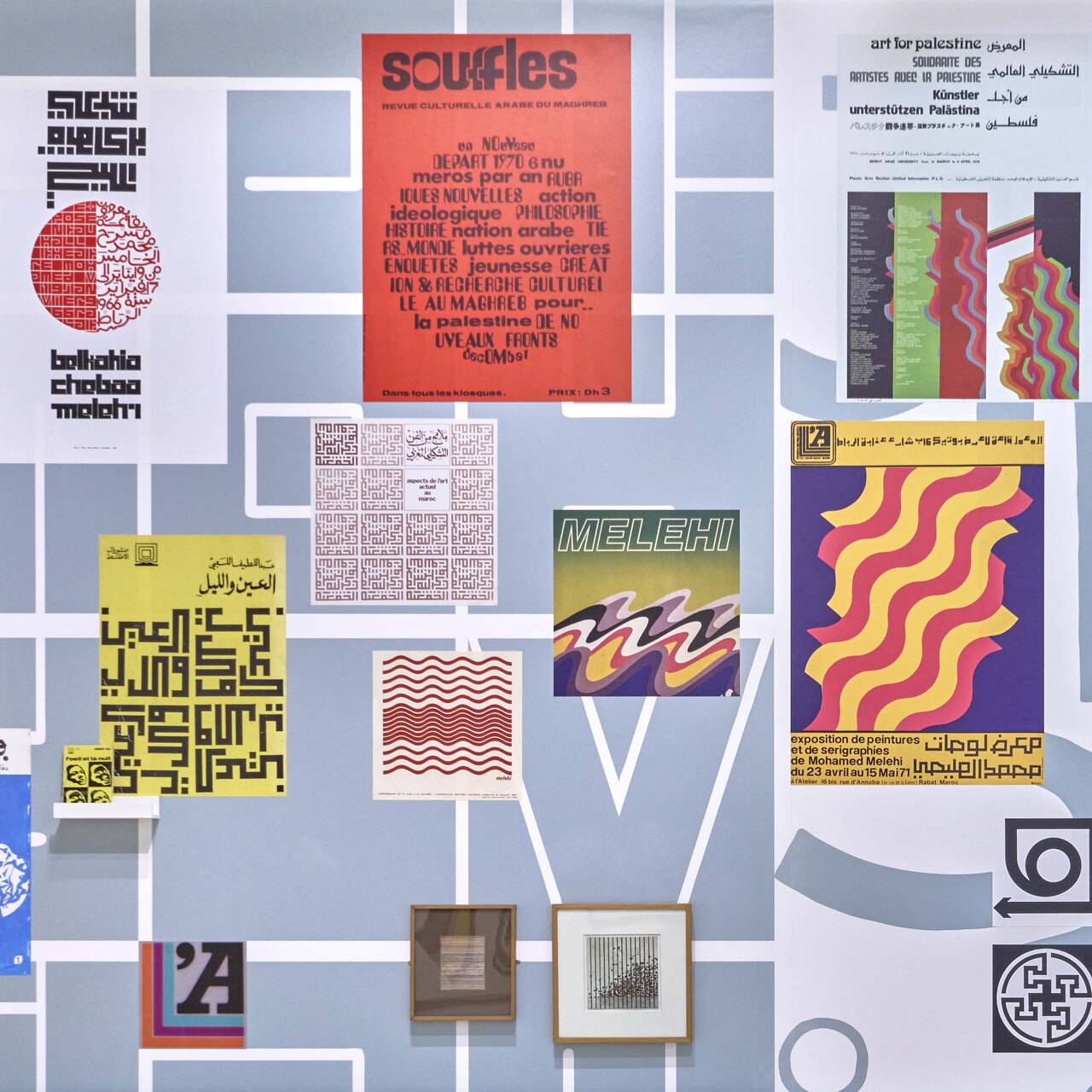

A lab for art in the public realm

The CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL wanted to make art part of urban life, visible for all, and interacting with the everyday culture of the city. To this day,...

Art and the world of journals in the Arab 20th century

Many of the teaching staff at the Casablanca Art School contributed to the journal “Souffles”, an extraordinary example for the strong...

A question of listening

Selma Selman creates her poetry of the future from multiple generations of Roma heritage completed with her subjective family story and history from...