Outlaws, those personifications of the Other, live according to their own moral code. They live unto themselves and attest to the vulnerability and the merciless authority of homogeneously structured groups. In the coming DOUBLE FEATURE Melanie Jame Wolf will present part of her “Creep-Studies”, in which she explores forms of structural power taking creeps and outlaws as her examples.

An outlaw stares down his opponent, with a challenging, self-confident, and at times scornful smile. The obligatory toothpick dangles leisurely from the corner of his mouth, his hands close to the imaginary holster – ready at any moment to shoot the opponent dead. The ambivalent figure of the criminal outsider, often shrouded in mystery, and it is one that points up an array of moral issues (from the incursion of uncivilized barbarity through to rebellious, individualist self-assertion) is at the very center of Melanie Jame Wolf’s “The Creep” (2023). The outlaw, the personified Other, ignores legal regulations and social conventions alike. Outlaws live according to their own moral code, live unto themselves, and at the same time attest to the fragility as well as the merciless authority of homogeneously structured groups. However, first things first: “Ooh! Get away with it for long enough, and it’ll start to look like fate” sings a voice, its tone evidently artificially altered, at the beginning of Wolf’s video piece, a voice that is thereafter repeatedly to be heard qua unreliable narrator.

The creep as a state of being

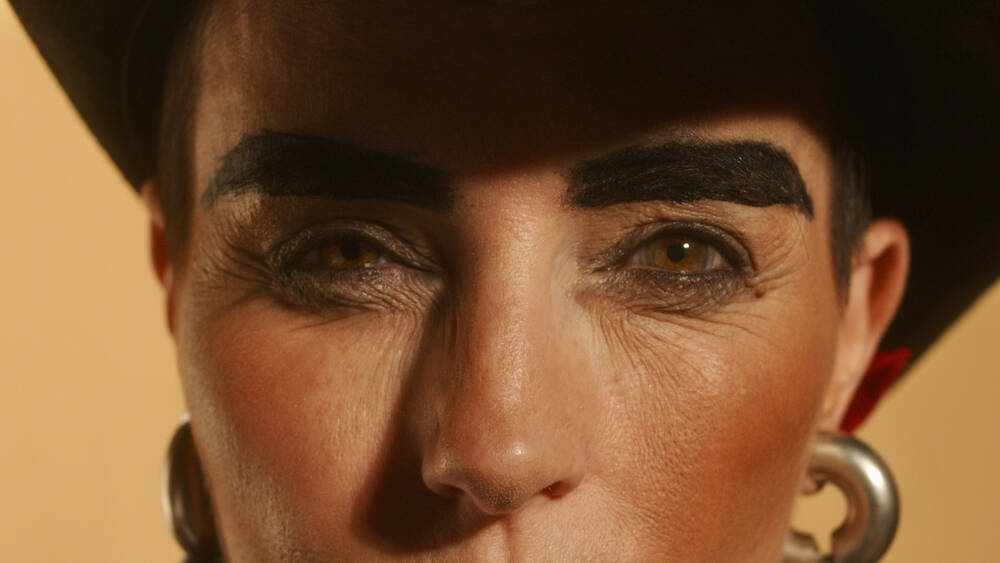

The piece is part of her ongoing “Creep-Studies” in which the artist and choreographer addresses forms of structural power, or to be more precise, with how forms of power aggregate and maintain themselves. “Creep studies play out of my fascination with how phenomena move or operate in imperceptible and incremental ways. […] Creep as a mode of being or as an organizing principle,” Melanie Jame Wolf commented in an interview with curator Adriana Tranca. Th ambivalence of the notion of the creep, with its associations of crawling, but which as a noun describes the figure of the mean creep, melds in the video work with that of the outlaw, whose modus operandi can be termed that of creeping. Wolf stages the creep/outlaw using minimalist sets and a visual language which in its use of close-up brings to mind the Spaghetti Western and with its lighting is reminiscent of the Hollywood Films of the 1950s: The figure rides a pommel horse against a background lit in orange, or in the next scene stands in front of a set illuminated in moody blue. Cicadas chirp, evidently a camp fire has been lit near-by and crackles away gently causing a shimmering of the light, while in the background there’s the intimation of a dark mountain range. The narrator voice starts up again, describes mountains, waves, clouds, before adopting a more somber undertone, and all the while the Outlaw/Creep is staring thoughtfully into the distance or is skipping about slightly.

There are echoes of Walter Benjamin’s concept of “mythical violence” to be discerned in the piece. The philosopher used the term to describe that essence of violence as is expressed, for example, by violence on the part of the state and in the linguistic domain is often to be detected in an “if, then” sentence structure. Increasingly, the violence seems to the individual to be a matter of nature and immutable. In a certain sense, it creeps in on us like a purported state of nature that in this way repeatedly reproduces itself socially and can never be fully pinned down. Melanie Jame Wolf appropriately had “The Creep” culminate in a showdown along with Sergio Leone-like close-ups as is typical of the genre of the Western reproduced here. However, in this case the outlaw challenges himself with exaggerated grimaces and theatrical postures – or is it more a matter of him challenging a split version of himself? In the final instance, it remains open as to who gains the upper hand. At the end all that remains is a carefully draped, huge red, latex sheet that resembles a huge pool of blood. “Ooh, the last refuge, the final parapets of petty tyrants and their states,” the narrator’s voice tells us for a last time.

A fucked-up, queer, upside-down West Side Story

Melanie Jame Wolf has chosen as her second film “Please Baby Please”, by US director Amanda Kramer. In the musical melodrama dating from 2022 a young couple Suze (Andrea Riseborough) and Arthur (Harry Melling) back in the 1950s witness an act of violent crime directly outside the front door of their spartan apartment on New York’s Lower East Side. The encounter with the perpetrators, all of them members of the “Young Gents” gang, makes a lasting impression on the couple. As we watch, the archaic aura of the juvenile delinquents who seem to completely reject all bourgeois conventions captivates Suze and Arthur and, in the process, also puts paid to their traditional notion of their roles. The musical draws here aesthetically on such film icons as Kenneth Anger or Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who for his part was strongly inspired by 1950s musical director Vincente Minnelli when making his homoerotic movie based on Jean Genet’s “Querelle”. Amanda Kramer stresses that it is key that her film is by no means “retro” in the sense of an accurate reproduction of a past time. Instead, her movie highlights discourses relating to the understanding of roles in relationships between couples, something that is of importance precisely today. Kramer herself concludes that essentially her movie is a “fucked-up, queer, upside-down West Side Story.”

Amanda Kramer, Please Baby Please, 2022, Image via riotmaterial.com