He came from a good family, had no financial worries and was short-tempered: Richard Gerstl’s style was so ground-breaking and alien that he never had an exhibition during his livetime.

The Academy of Fine Arts Vienna is the oldest art college in central Europe. Founded in 1692, in 1877 it moved into a building constructed especially for it, a magnificent palace on Schillerplatz – where it is still located today. Around 1900 however, after the two artists’ associations Vienna Secession and Hagenbund had been established, it no longer enjoyed its earlier undisputed importance. Richard Gerstl was enrolled at the Academy as a student as of winter semester 1898/99, although not continuously. He had a difficult and generally discouraging relationship with his teachers and was largely isolated.

Gerstl came from a middle-class family. He embraced apodictic opinions, and having no money worries could also afford to have them. He was already considered a difficult student during his school days at the renowned Piaristengymnasium. His father tolerated Gerstl’s artistic ambitions, his mother supported them, and he got on well with his brother Alois, who would later document Richard’s far-too-short life.

Griepenkerl and Adolf Hitler

Even as a schoolboy Gerstl received instruction in drawing from Academy student Otto Frey. Following his fourth year at high school he attended the drawing school “Aula” for two months to study for the entrance examination to the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. He passed the examination and from October 1898 the 15-year-old attended the “Allgemeine Malerschule” (foundation painting classes) of Christian Griepenkerl (1839-1916).

Christian Griepenkerl, Image via meinbezirk.at

Griepenkerl was a German-Austrian painter who specialized in monumental historical painting and later portrait painting. He was arguably the most reactionary teacher employed at the Academy at the time. But there was no getting around his foundation classes, and his students also included Carl Moll and Egon Schiele. Today, Christian Griepenkerl’s artistic oeuvre is considered unimportant, but the fatal decision he would take to reject the application of Adolf Hitler to study at the Academy in 1908 would help assure him posthumous immortality.

Progress, finally!

Presumably the instruction Gerstl received under Griepenkerl was unproductive, and his relationship to his professor characterized by differences of opinion. Indeed, one day Griepenkerl hurled the words “The Devil sent you to the Academy,” at his student, on another occasion he gave him a dressing-down, claiming: “The way you paint looks like pissholes in the snow!”

Carl Moll, Image via wikipedia.org

Around this time Gerstl was accepted into the group centered round Arnold Schönberg and Alexander von Zemlinsky and found like-minded people amongst these progressive musicians. Here he finally met creative people who were open to new ideas and prepared to embark on totally different paths and reject classic models.

Regression through conformation

Gerstl had a single friend at the Academy, Victor Hammer, whom he addressed formally. While visiting Victor Hammer, Heinrich Lefler (1863-1919) saw Gerstl’s large double portrait of the Fey sisters, which reflects Manet’s painting technique, while the composition is influenced by Munch. The professor is so impressed that he accepts Gerstl into his “Systematisierte Spezialschule für Landschaftsmalerei” (Systematized special school for landscape painting), meaning that Gerstl was able to resume his studies in summer semester 1906.

Arnold Schönberg, Image via wikipedia.org

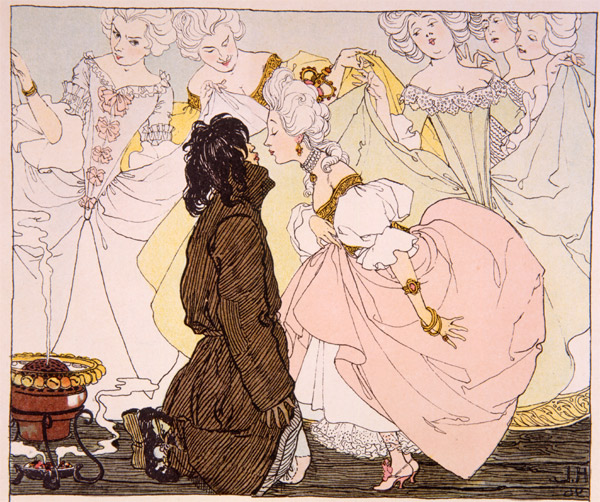

Illustration by Heinrich Lefler to: Hans Christian Andersen, Wien 1897, Image via commons.wikimedia.org

First of all, three possibilities to exhibit his work came to nothing. Presumably concerned about the scandal his participation might cause, Lefler did not allow his student to take part in a Hagenbund exhibition; then the “Ansorge-Verein” retracted its offer for an exhibition; and finally Gerstl himself turned down an opportunity to exhibit at the renowned Galerie Miethke run by Carl Moll, because his work was to hang next to that of Gustav Klimt, whose art he detested. Nobody understood this radicalism, but Gerstl refused to listen to reason.

Opposition to authority

In the fall of 1907 Lefler withdrew his student’s privilege of a private studio. Subsequently, when Gerstl heard that Heinrich Lefler together with Josef Urban, Oskar Kokoschka and other artists had been given the socially prestigious commission of designing the procession to mark the diamond jubilee of Emperor Franz Joseph I, he recklessly criticized his professor, arguing that an artist who had a good opinion of himself would not deign to deal with that kind of thing.

On July 19, 1908, one week to the day after the imperial anniversary, a group exhibition of Heinrich Lefler’s class opened. Without his knowledge, Gerstl’s teacher had excluded the rebellious student from the exhibition. On hearing of his exclusion, an outraged Gerstl, who had already left for Traunsee with the Schönberg group, wrote a letter of protest to the Ministry of Culture and Education. As this letter of complaint to the Ministry is so far ahead of its time in its opposition to a professor’s authority, we would like to quote a short excerpt from it:

Rather than responding to the complaint, the Ministry passed the letter to the Dean of the Academy, who also failed to answer it and considered the matter closed. Years later Alois Gerstl remembered that his brother was subsequently expelled from the Academy. However, no entry to this effect is made in Gerstl’s file in the Academy archives. But one way or another, this would have been of little interest to Gerstl, who following the exposure of his affair with Mathilde Schönberg fell into an emotional crisis, which as we know would ultimately end in his suicide.

He (namely I) has a totally different approach, and he is difficult to follow, but I can do nothing for him.

The film to the exhibition: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN...

A new look at the artist – “L’altra metà dell’avanguardia 1910–1940”

With “L’altra metà dell’avanguardia 1910–1940”, in 1980 Lea Vergine curated an exhibition at the Palazzo Reale in Milan that was one of the first...

Non-human living sculptures by Hans Haacke and Pierre Huyghe

In his early work, HANS HAACKE already integrated animals and plants as co-actors into his art. In that way he not only laid the foundations for a...

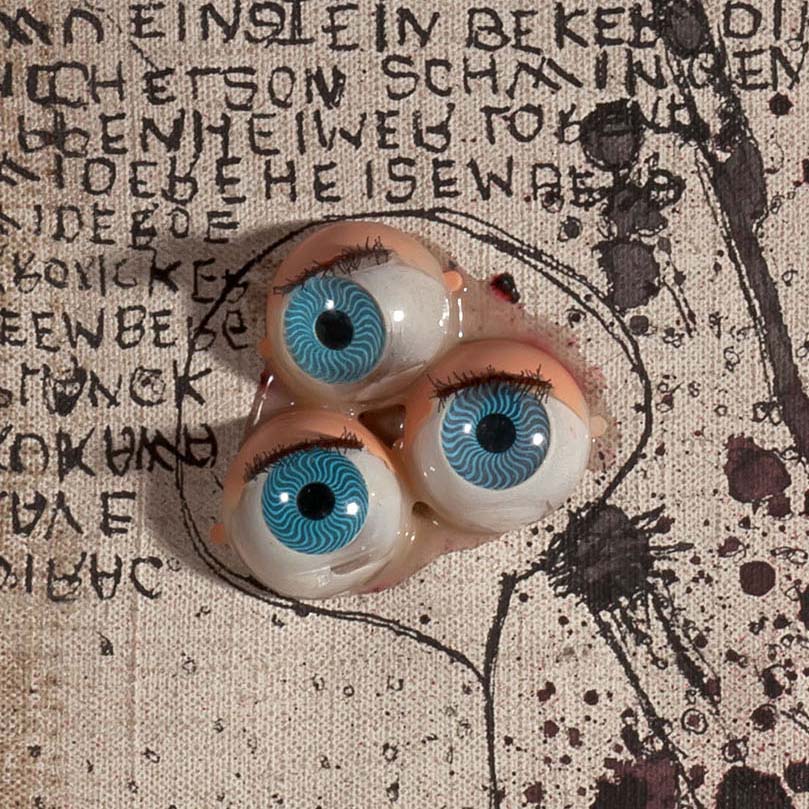

CURATOR TALK. CAROL RAMA

SCHIRN curator Martina Weinhart talks to Christina Mundici, director of the Carol Rama Archive in Turin, editor of the first Catalogue Raisonné and...

Freedom costs peanuts

HANS HAACKE responded immediately in 1990 to the fall of the Berlin Wall and turned a watchtower into art.

The film to the exhibition: CAROL RAMA. A REBEL OF MODERNITY

Radical, inventive, modern: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN provides insights into CAROL RAMA's work.

Now at the SCHIRN: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: the SCHIRN presents the groundbreaking work of the compelling...

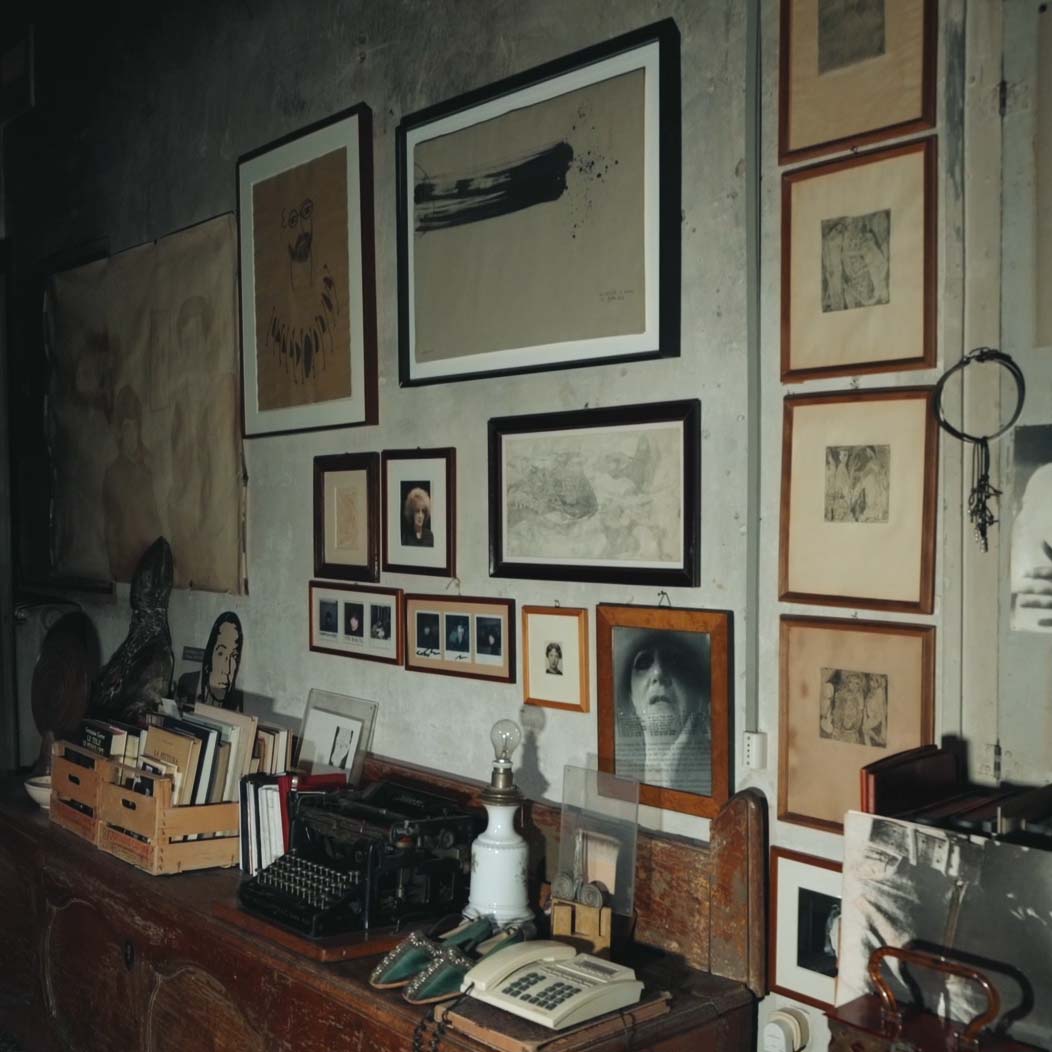

Carol Rama’s Studio: A nucleus of creativity

CAROL RAMA determinedly forged her own path through the art world. Her spectacularly staged studio in Turin was opened to the public only a few years...

PANEL: POLITICAL ACTIVISM BY SELMA SELMAN

Hosted by Arnisa Zeqo, Amila Ramović and Zippora Elders speak with the artist Selma Selman about her artistic career, the exhibition SELMA SELMAN....

Now at the SCHIRN: Carol Rama. A rebel of Modernity

Radical, inventive, modern: the SCHIRN is presenting a major survey exhibition of CAROL RAMA’s work for the first time in Germany.