Every generation critically addresses their predecessors: In the 1960s, it was Funk Art in California that reacted to Abstract Expressionism and inspired Peter Saul.

By banning the figurative element from painting in favor of an abstract analysis of the “crisis of modern man” and also resorting to images from archaic cultures, artists such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko or Willem de Kooning shaped the Abstract Expressionist movement in the 1940s and 1950s. They saw art as providing an opportunity to criticize progress and an answer to race riots, totalitarian regimes and the effects of the war.

Viola Frey, Man Kicking World II, Cameron Art Museum in Wilmington, North Carolina, Image via flickr.com

The tide turned when in the late 1950s the “Bay Area Figurative Movement” began to form in San Francisco from the ranks of the Abstract Expressionists: an increasing number of artists now criticized the non-figurative nature of Abstract Expressionism and revisited figuration. The candid and experimental scene around the late Beatniks and early hippies in California also provided fertile creative ground, from which so-called “Funk Art” was later to arise.

Humorous and vulgar

In contrast to their socio-critical precursors, the Funk Art artists, and they included Wally Hedrick, Jay DeFeo, Viola Frey and Bruce Conner, did not focus on the surrounding world in their art work, but instead on their own sensitivities. They did not regard themselves as being a fixed group and rejected all shared definitions of their art – but what all of their approaches had in common was the passion, the playfulness and the scurrility of their works, which could be described using the term “funky”, coined in the Jazz scene in the 1920s. They allowed their emotions and psychological processes to become part of their work in revealing ways, often paired with a lot of humor, irony and at times vulgar depictions of sexuality.

Bruce Conner, SNORE, 1960, Image via Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Funk Art did not conform to the stylistic and aesthetic demands made of art at that time in the least: The assemblages and installations were much to chaotic to be Minimalist, too figurative for Abstract Expressionism, and the biographical features of the sculptures too obvious and too personal to be taken seriously. As regards their critique of consumer culture, references to Pop Art are evident, but many of the works seem clumsy – which may be one of the reasons why Funk Art was known almost exclusively in the Bay Area and now appears as little more than a footnote in 20th century art history.

Society in the pillory

Yet this did not bother the artists themselves. In the late 1950s, Bruce Connor, one of the first “Funk Artists,” collected finds from modern throwaway culture and with his assemblages made of consumer waste indirectly castigated a society that celebrated consumerism and waged wars instead of fighting for a peaceful life together. Edward Kienholz – who hovered between Funk Art and Pop Art – also made recourse to this method in creating his “objets trouvés,” with which he drew attention to discrimination and double standards in society.

Mowry Baden, Delivery Suite, 1965, Image via mowrybaden.com

Viola Frey’s larger-than-life sculptures in turn raise issues of gender-stereotyping, something that the renowned ceramicist had to experience personally; and after having worked on it for ten years, Jay DeFreo created a painting that weighed over a ton and had to be lifted from his flat with a crane with “The Rose”. Peter Saul, who had previously lived in Europe for a while, settled in the Bay Area in 1964 and painted ironic-kitschy works on the Vietnam War as well as overly stylized portraits of politicians in bright colors.

The installations and assemblages of the “Funk Artists”were often geared towards including the viewers, allowing them to smell the odor of decay and criticism and experience it firsthand – an interactivity that had not previously existed in the art world in quite this way. And as adverse as they were to being lumped together: The “Funk Art” artists all provided a playful-ironic questioning of the definitions of art prevalent at the time.

The film to the exhibition: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN...

A new look at the artist – “L’altra metà dell’avanguardia 1910–1940”

With “L’altra metà dell’avanguardia 1910–1940”, in 1980 Lea Vergine curated an exhibition at the Palazzo Reale in Milan that was one of the first...

Non-human living sculptures by Hans Haacke and Pierre Huyghe

In his early work, HANS HAACKE already integrated animals and plants as co-actors into his art. In that way he not only laid the foundations for a...

CURATOR TALK. CAROL RAMA

SCHIRN curator Martina Weinhart talks to Christina Mundici, director of the Carol Rama Archive in Turin, editor of the first Catalogue Raisonné and...

Freedom costs peanuts

HANS HAACKE responded immediately in 1990 to the fall of the Berlin Wall and turned a watchtower into art.

The film to the exhibition: CAROL RAMA. A REBEL OF MODERNITY

Radical, inventive, modern: The film accompanying the major retrospective at the SCHIRN provides insights into CAROL RAMA's work.

Now at the SCHIRN: Hans Haacke. Retrospective

A legend of institutional critique, an advocate of democracy, and an artist’s artist: the SCHIRN presents the groundbreaking work of the compelling...

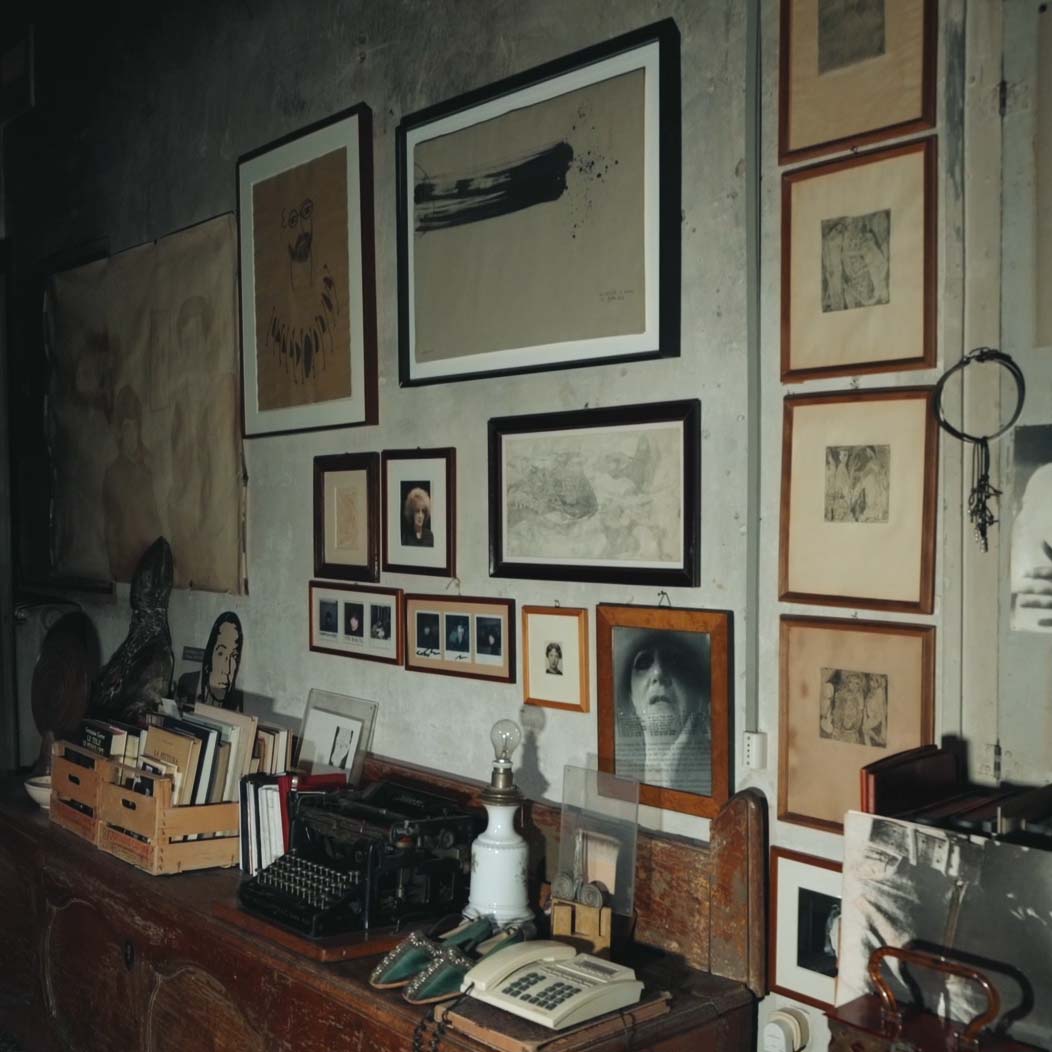

Carol Rama’s Studio: A nucleus of creativity

CAROL RAMA determinedly forged her own path through the art world. Her spectacularly staged studio in Turin was opened to the public only a few years...

PANEL: POLITICAL ACTIVISM BY SELMA SELMAN

Hosted by Arnisa Zeqo, Amila Ramović and Zippora Elders speak with the artist Selma Selman about her artistic career, the exhibition SELMA SELMAN....

Now at the SCHIRN: Carol Rama. A rebel of Modernity

Radical, inventive, modern: the SCHIRN is presenting a major survey exhibition of CAROL RAMA’s work for the first time in Germany.

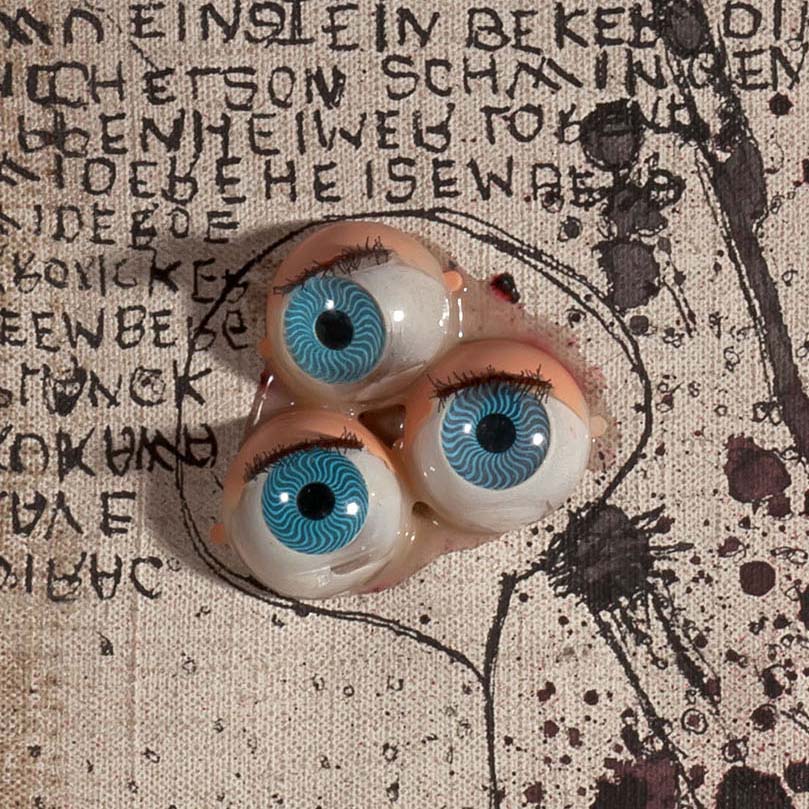

Carol Rama in 10 (F)Acts

CAROL RAMA was one of the most provocative female artists of the 20th century. With her explicit depictions of sexuality, physicality, and tabooed...

A lab for art in the public realm

The CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL wanted to make art part of urban life, visible for all, and interacting with the everyday culture of the city. To this day,...