Can you simply assign objects new names? In his “word-image paintings” Magritte employed the linguistic theories of Ferdinand de Saussure – and questioned the complex system of language.

“Le ciel” – the sky – is written in flowing lettering on a black background. Above the words we see a brown travel bag. At the bottom edge of the picture the artist has painted the green leaf of a tree, bearing the subtitle “la table,” the table. What has gone wrong here?

Did Magritte mistakenly get the words mixed up while painting “L’interprétation des rêves” (The Mystery of the Ordinary)? Viewing the painting, we notice an instant resistance, and the thought “But that’s a bag and not the sky!” gets louder before quiet confusion sets in. And that means Magritte has achieved what he set out to do.

Banishing all logic

“No object is so firmly associated with its name that one couldn’t give it a different one that better suits it,” wrote Magritte in 1929 for the Surrealists’ own publication “La Révolution surréaliste” in something like a catalog of definitions called “Les mots et les images” (Words and images). With this statement Magritte offers us an explanation for his enigmatic pictures in which objects and their names confusingly do not match up.

In so doing, he follows in the footsteps of the artists grouped around André Breton, who had banished all logic from Surrealist poems and paintings. In their art, words should never mean what they normally mean, for the connection between an object and its name is absolutely arbitrary and the two do not depend on each other. Anyone who sees a chair thinks “chair,” and anyone hearing the word “chair” sees the image of a chair in their mind’s eye.

It is purely coincidence that a tree is called tree

The name of an object makes depicting that object superfluous, Magritte claims, and paints a square box with the word “ciel” in the center, with no sky in sight. In a lecture on his word-image paintings that he gave in London in 1937 he proved his theory by replacing the word “sun” in an essay by André Breton by a drawing of a sun – and still everyone understood.

It is highly probable that while he was creating his word-image paintings Magritte was very well acquainted with the linguistic theories of Ferdinand de Saussure, which a few of the latter’s dedicated students had published after his death in 1916. Saussure was already convinced that “The link between signifier and signified is arbitrary.” A tree is only called tree by coincidence, he claimed, and could just as well bear a different name.

Language is a fluid process

A glance at the different signifiers in other languages confirms this; here the object in question is called “Baum,” “arbre” or “árbol” and could just as easily be “larn” or “wolk.” And yet we as individuals don’t have the option of consciously changing language, of deciding today that as of tomorrow a tree will be called something else. Language is indeed a constantly fluid process, but it is unconscious and only comprehendible when the change has already occurred.

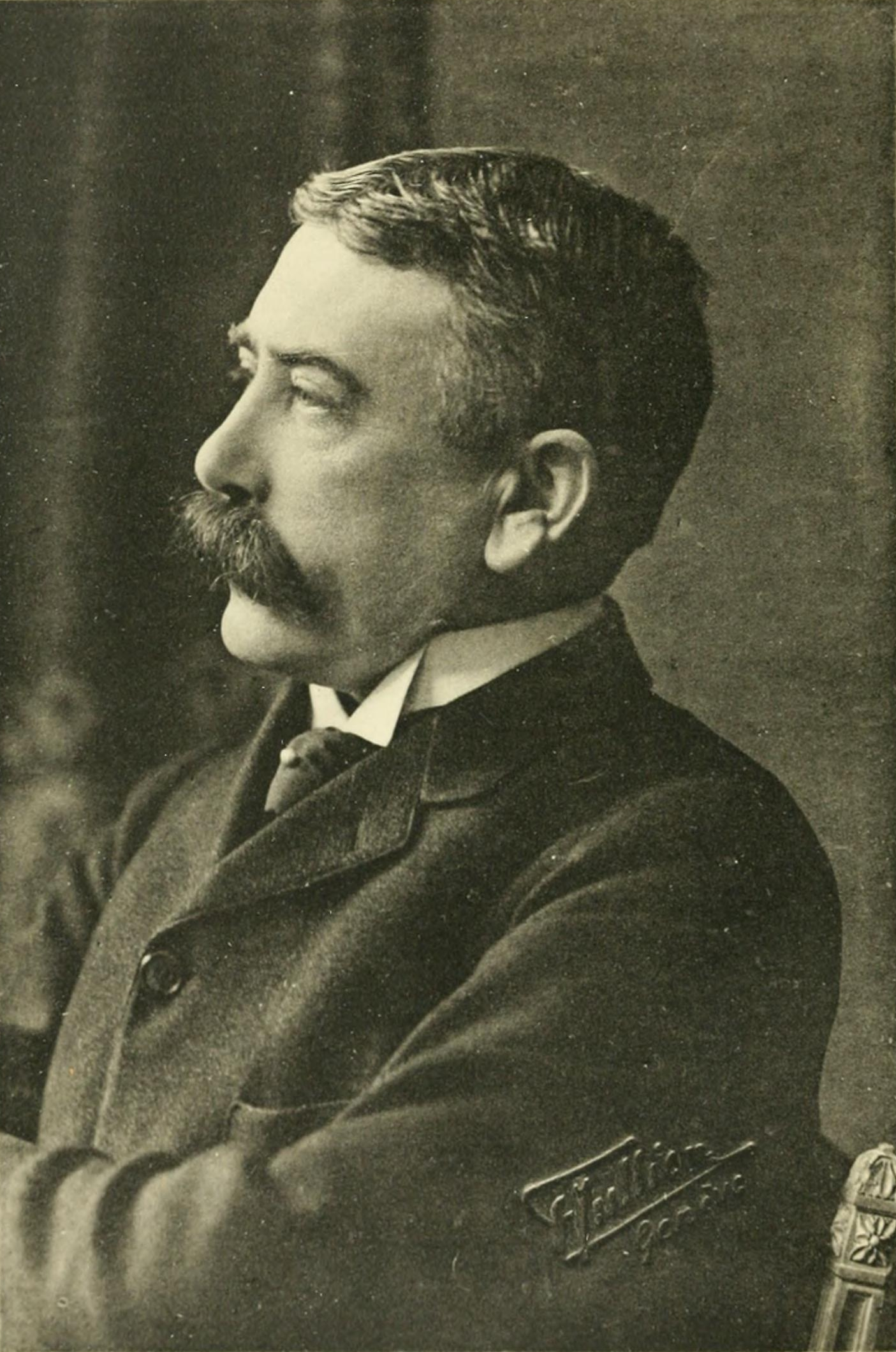

The Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure (1857–1913), photo by "F. Jullien Genève", maybe Frank-Henri Jullien (1882–1938) (Indogermanisches Jahrbuch) [Public domain or Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

In his paintings Magritte toys with the arbitrary connection between object and designation in order to make the observer stop and think and question not only everyday objects and their names, but also the automatic mechanisms of thought. Does the name even suit the object? Does not the word “cupboard” take on a strangely alien quality when you murmur it repeatedly to yourself? And are not all names only notions of that which they designate anyway?

Can you stuff Magritte’s pipe?

“Ceci n’est pas une pipe,” one of Magritte’s best-known word-image paintings, makes the observer realize that precisely this is a troubled theory. “Of course it’s a pipe, what else?” we think. We have seen pipes often enough and most of them resembled the painted one, even in the details. And precisely there is the answer: It is only a painted pipe, not a real one, one you could touch. “One mustn’t mistake a picture for an object that one can touch. And yet, could you stuff my pipe? No, it’s just a representation, is it not? So if I had written on my picture, ‘This is a pipe,’ I’d have been lying. A representation of a jam sandwich is certainly not something that can be eaten,” says Magritte.

One mustn’t mistake a picture for an object that one can touch […]

By decoupling from its designation an everyday object whose name we can recall without much thought and giving it another, Magritte makes us stop and think: Why is a shoe actually called shoe and not lamp? Why do we all think of roughly the same object when we read the sequence of letters “tree” and not each of us of something entirely different? And why does a simple observation – this is not a pipe – cause such confusion?

Backdoors and stumbling blocks

Magritte wanted to take habitual seeing and talking patterns in observers of his paintings to an absurd extreme. Yet he didn’t do this with his finger wagging, but with a mischievous smile. The roguish artist was inspired by an unbridled enjoyment of wordplay, a passion stemming from his Dadaist phase, where the focus was on the deconstruction of standard language. Our language is a finely branched system with a great many backdoors and stumbling blocks and we should not take it for granted. Magritte knew that.