In the Geneva Freeport complex alone there are said to be round 1.2 million works of art (including Nazi looted art). The artist of the upcoming double feature, Maeve Brennan, follows forensic archaeologists on the job, an undertaking that fluctuates between detective work and the reconstruction of destroyed looted art.

It sounds like a reasonable premise for a heist movie: “The St. Gotthard duty-free warehouse is located in a former bunker deep inside a granite mountain massif. It has bullet and explosion-proof doors,” boasts the operator of the largest warehouse of its kind in Switzerland. Such duty-free warehouses for the storage of goods not only lack transparency but are also places steeped in legend. In the Geneva Freeport complex alone there are said to be around 1.2 million works of art (including Nazi looted art) – filmmaker Hito Steyerl spoke of “thousands of Picassos” stashed away there. Fittingly enough, since 2020 the duty-free warehouse has been run by an art historian and lawyer rolled into one. Fitting because for some time the criminal investigation agencies have had the location repeatedly in their sights, and on numerous occasions police have seized looted art in raids there. As happened in 2014, when Italian carabinieri recovered tens of thousands of looted archaeological artefacts largely of Etruscan provenance deposited there by the meanwhile disgraced antiquities dealer Robin Symes; they were stored in 45 crates and labeled “decorations”.

Geneva Freeport complex, Image via srf.ch

Insights into Forensic Archaeology

It was this sensational case that informs “An Excavation” (2022), the new work by Irish artist Maeve Brennan. Three of the confiscated crates ended up with forensic archaeologists Dr. Christos Tsirogiannis and Dr. Vinnie Norskov, both of whom were working at Aarhus University at the time. Right at the start, the film shows various shots of one of the stolen vases that had been reconstructed as far as possible. Cautiously the camera moves closer and closer to the artefact and shows its fracture lines on its surface while on the soundtrack we hear atmospheric sounds of a qanun being played. “I’ve always loved detective stories,” says Dr. Christos Tsirogiannis, a passion that evidently led to his becoming a forensic archaelogist. Together with Dr. Vinni Norskov he carefully sorts the individual fragments of the artefact, mostly vases that are thousands of years old; the two are now gradually reconstructing the original vases, whereby they are also evaluating other pieces of evidence such as Polaroids or packaging material.

The work by Tsirogiannis and Norskov represents an important contribution in the fight against the market in illegal looted art, which as we learn in “An Excavation” is part and parcel of the antiquities trade. While working on “The Drift” (2017) – a video project in which Maeve Brennan links three different biographies around archaeological artefacts, restoration and (the preservation of) monuments in Lebanon – local art thieves came to her attention. They casually told her where exactly most of the finds end up, namely largely in museums in London. Then, in 2017, Brennan heard about Dr. Christos Tsirogiannis, who in a sensational case had just identified two Greek vases at the London Frieze Masters art fair as looted art. Since 2018, the two of them have been collaborating on the ongoing project “The Goods” that is derived from the archaeologist’s archive (it consists of over 30,000 images) and hinges on displaying the stolen art on billboards.

“An Excavation” offers a fascinating, very poignantly filmed insight into the work of forensic archaeology. However, the issue of restitution and the structural problems of the art market as a whole always resonate in the background. It’s possible to trace how this all plays out on the website operated jointly by Brennan and Tsirogiannis (illicitantiquities.net). The site allows visitors to track the various trade routes of illegally appropriated artefacts and shows how they eventually end up in museums and galleries in London and New York. Battling these circumstances would seem to be a task of Sisyphean proportions. Maeve Brennan’s film that has the flavor of a documentary essay, portrays the struggle in a similar way to how the work of the forensic archaeologists is depicted: it is as calm as it is sensitive, but also tenacious.

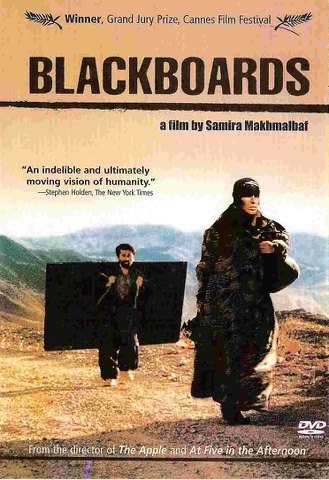

Samira Makhmalbaf’s “Takhté siah”

The film chosen by Maeve Brennan to accompany hers is “Takhté siah” (Blackboards), produced by Iranian director Samira Makhmalbaf. The film was released in 2000 and in parts takes on almost documentary traits, accompanies two itinerant teachers in the border area between Iraq and Iran at the time of the Gulf War. In the course of the film, both men, who are actually looking for students whom they can teach to read and write, encounter Kurdish refugees whom they then join on the arduous journey to Iran. The horrific historical reality against which “Takhté siah” takes place – the Iraqi military’s poison-gas attack on the city of Halabja, which they considered the center of the Kurdish resistance), and which killed 5,000 people – weighs down on the film like a heavy veil.

movie poster: Samira Makhmalbaf, Blackboards, 2000, Image via worldscinema.org

Samira Makhmalbaf, who was just 20 years old at the time the film was released, wrote the screenplay with her father Mohsen Makhmalbaf, himself an internationally acclaimed director. Filmed completely in Kurdish and performed by amateur actors, the film’s narrative provides a moving insight into lives marked by flight and poverty. As it unfolds so it repeatedly develops philosophical and poetic overtones.

However, both the work of Samira Makhmalbaf and that of Maeve Brennan also point to the lack of legal action taken: There is a reluctance to deal with claims for restitution from Mediterranean countries or those that were formerly colonies. Indeed, sometimes such claims are ignored altogether. And the victims of the poison gas attack under Saddam Hussein’s regime are also still waiting in vain for legal action to be taken – not only against the people responsible in Iraq, but also against the European firms who provided the regime with the technical know-how for the production of the poison gas