Belinda Kazeem-Kamínski’s video piece is dedicated to a letter written by Yaarborley Domeï. This rare testimony to a past time describes not only Domei’s experiences in the context of a so-called “ethnographic exhibition”, but also contains notions that would today be considered intersectional.

In Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński’s video “The Letter” (2019), the first few seconds are taken up by complete silence before slowly a low-frequency droning picks up, although the screen remains black. A voice then speaks off-screen: “We have read your letter. Many years have passed and finally it has reached us.” At the same time, higher-frequency tones join the humming and interweave to form a more complex harmony. The letter from which the video’s title derives and to which the voice refers forms the central element in the video piece. Yaarborley Domeï wrote the epistle in 1896 and it was published in the newspaper “Wiener Caricaturen”. Domeï was a member of a group of people who at the end of the 19th century had been transported from West Africa to Vienna where they were lodged in a zoo in the framework of a so-called “ethnographic exhibition” (in reality nothing more than a ‘human zoo’).

There they were supposed to recreate everyday life in an imagined African village. Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński first found out about these exhibitions at the age of 26 on reading the book “Ashantee” by Austrian author and self-confessed pedophile Peter Altenberg. The problematic book continued to trouble her for a long time after: “On the one hand, people repeatedly emphasize that Peter Altenberg was very critical of these ’exhibitions’. At the same time, he himself regularly visited them and he relied precisely on the infrastructure they offered to play out his own exoticisms, racisms, sexisms, and his proclivity for underage girls.” For her piece entitled “Ashantee, edited” (2017–2021) Kazeem-Kamiński quite literally scratched those sentences and passages that were informed by racism and sexism out of the book, such that only the name of the performers and a few words remain in Ga, one of the 16 different languages spoken in Ghana.

Searching for evidence in the former Völkerkundemuseum Wien

In “The Letter”, after the establishing sequence the film camera’s lens opens and we are offered a view of a long corridor inside a building. Three persons whom Vienna-based Kazeem-Kamiński describes as so-called ‘empaths’ walk along the corridor, don black gloves, and eventually enter a room. The artist, author, and scholar shot the film in the archive of Weltmuseum Wien, the ethnographic museum of non-European cultures that houses the collections of the former Völkerkundemuseum.

The three persons we see seem to be trying to find traces of the life of Yaarborley Domeï, busily open countless cupboards and drawers in the archive, and seek anything they can find relating to her. Parts of the letter mentioned in the title are read out as part of the soundtrack – again in Ga. In them, the West African woman tells white people exactly what she thinks about them. “What I find interesting about this letter,” Kazeem-Kamiński says, summarizing this rare document of the day, “is that Yaarborley Domeï articulates a perspective that we would today term intersectional. She highlights the interweaving of different forms of discrimination and addresses racism and sexism.

“Fleshbacks” (2021) can be viewed as a tripartite annotation on “The Letter” in which the artist transposes the action from the archive into the outdoor world. Protagonists move through urban space; close-ups of their faces alternate with archive photographs of those people who were placed in the ‘human zoo’ in Vienna over a century ago until gradually the screen is covered with images from the Ghanaian capital of Accra. Present and past thus interact, something the filmmaker tries to capture with her neologism “fleshback”. The word describes that “moment in which black people become aware of the present past and its corporeal reality […]: their history, degradation, the fact that they were made into objects, something that continues to the present day. At the same time, these moments also bring to mind community, a common bond, resistance, and specific cultural articulations.”

On the heritage of the colonial past

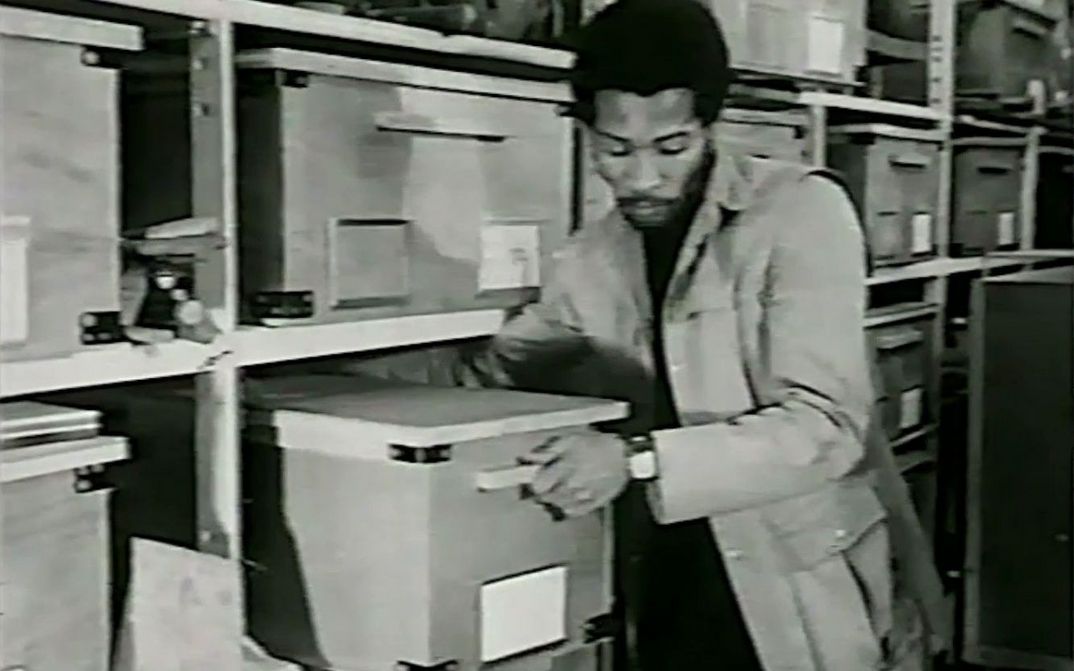

Belinda Kazeem-Kamiński has chosen as other works two short films, namely “No Archive Can Restore You” (2020) by Onyeka Igwe and “You Hide Me” (1970) by Nii Kwate Owoo. In her short film, Onyeka Igwe goes on a tour of the now decrepit interior of the former Nigerian Film Unit building in Lagos, one of the first independently-operating field offices of the British propaganda production company, the Colonial Film Unit. The heritage of a colonial past resounds in the film rolls found there; they had initially been considered lost and given their poor state can only be screened with great difficulty. Nii Kwate Owoo managed back in 1970 to trick the museum management and the entire security apparatus of the British Museum and gain access to the underground storerooms to make his short film “You Hide Me”. The invaluable African artifacts he filmed there, stored in plastic bags and wooden crates, give an idea of the wide extent of the colonial theft of indigenous art. In 2023, the British Museum continues to thwart the restitution of the artefacts.

Onyeka Igwe, No Archive Can Restore You, 2020, film still © the artist, Image via artsfoundation.co.uk

Nii Kwate Owoo, You Hide Me, 1970, Image via arsenal-berlin.de