What happens when the instruments are swapped in an orchestra? And how do animals react to pieces of music? Annika Kahr’s video works explore the diverse possibilities of sounds.

With the exhibition “We Have Delivered Ourselves from the Tonal – Of, with, towards, on Julius Eastman” and the accompanying two-day symposium, the 2018 MaerzMusik festivalin Berlin placed the focus on the long forgotten Afro-American composer, pianist, singer and dancer Julius Eastman. Various artworks were commissioned to address the question of how Eastman’s artistic practice is manifested in current cultural, political and spiritual contexts.

Right at the beginning of the exhibition visitors encountered Annika Kahrs’ work “the lord loves changes, it’s one of his greatest delusions” (2018), which was in turn co-produced by MaerzMusik.

An argument with John Cage ended Eastman’s promising career

In the context of New Music, Eastman’s compositions can be classified as Minimal Music. In the 1960s, the composer found acclaim first as a pianist and later also as a singer, before in the 1970s being awarded a scholarship at the renowned Buffalo Center for the Creative and Performing Arts, where he eventually ended up teaching music theory. After coming to blows with composer John Cage, Eastman left the university, and in the early 1980s saw himself faced with a discouraging and seemingly total lack of professional perspective. He increasingly attempted to assuage his despair with alcohol and drugs.

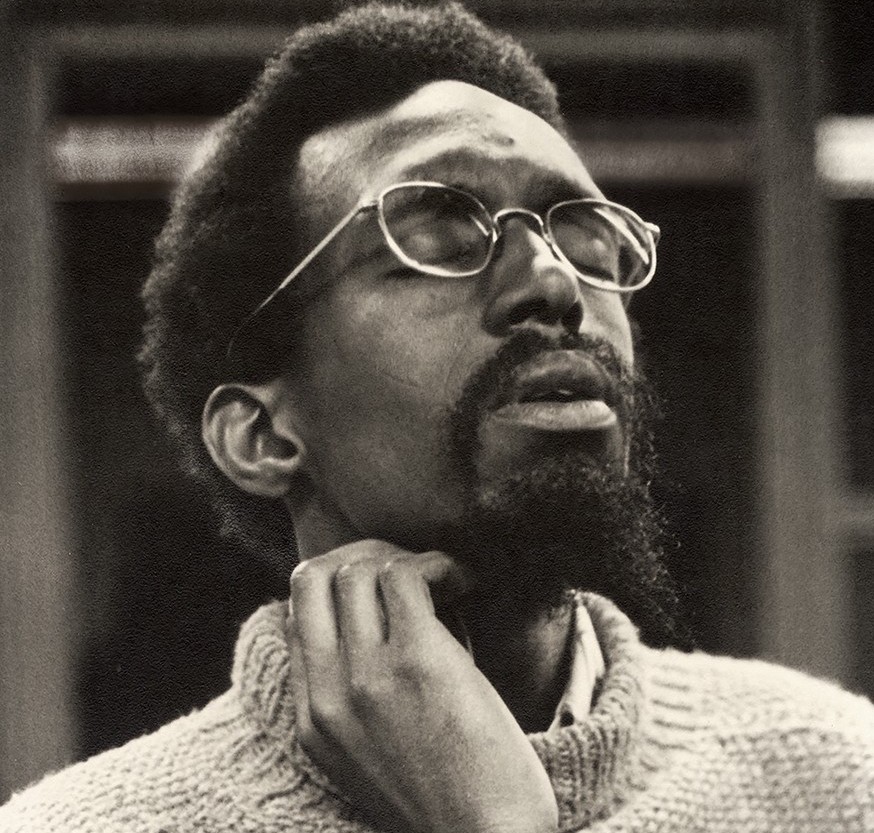

Julius Eastman, 1974, © 123RF.com © Archiv Die Neue Südtiroler Tageszeitung GmbH, Image via tageszeitung.it

Eastman lost everything he possessed and lived as a homeless person in state institutions or at the houses of friends. In 1990, he died of a circulatory arrest, unnoticed by the musical public – the New York City magazine “Village Voice” only drew attention to his death some eight months later.

Annika Kahrs’ video piece “the lord loves changes, it’s one of his greatest delusions” is over 15 minutes long and based on two pieces by Julius Eastman, namely “The Holy Presence of Joan d’Arc” and “Gay Guerrilla”, both of which were composed in the early 1980s. Eastman had further used Luther’s reformation choral “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” in “Gay Guerilla”. In Annika Kahrs’ video we see a choir enter the empty Laeiszhalle in Hamburg with its echoing acoustics, then an organist plays the first notes. The pace-setting, metallic organ pipes, which translate the notes played into audible sounds, are joined by the whistling of a 28-person choir.

Every individual whistling sound differs minimally or rather micro-tonally from the clearly intoned organ, which gives rise to a highly dissonant sound structure that diverges more and more from the organist’s guideline. Interesting harmonies arise momentarily, then the whistling sounds become reminiscent of ghoulish wind and finally the human whistling appears to become ever more mocking, maybe even to protest against the organ melody. Over the course of the performance the discord becomes ever more piercing, the whistling of the choir becomes louder, more chaotic and more demanding for the individual performers – more and more of them sit down on the floor as the piece progresses. After around 14 minutes the music slowly subsides, the camera reveals the view of the Neo-Baroque music hall with its choir and the organist for the first time, the participants now looking literally deflated.

Kahrs‘ repeatedly addressed the possibilities of sound

Annika Kahrs’ work, consisting of video works, performances, photo series or installations, has repeatedly addressed the possibilities of sound. In “Playing to the birds” (2013) she had a pianist play Franz Liszt’s piece for piano “Die Vogelpredigt des heiligen Franz von Assisi” (trans. “St. Francis of Assisi Preaching To The Birds”) to an audience of songbirds and parrots, in “Strings” (2010) the musicians of a quartet swapped instruments in the middle of playing Beethoven’s String Quartet No. 4 in “C Minor Op. 18”.

In her three-channel installation “Infra Voice” (2018) Kahrs has the Norwegian composer and musician Guro Skumsnes Moe play a piece written for the occasion on the octobass – an instrument able to produce sounds lower than the human audible spectrum – show alongside this the recording of a giraffe as it presumably also communicates with conspecifics in the same range of frequencies.

Sounds, one might think, convey messages: Heinrich Heine thus described Luther’s choral “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” as the hymn of reformation, while Friedrich Engels describes it as the “Marseillaise of the Peasants’ Wars” and indeed the song was given a new interpretation as a battle song, beginning with the so-called Wars of Liberation in Germany. Julius Eastman in turn weaved Luther’s work into a manifesto of sorts for the gay liberation movement. In reference to that historical protest anthem, “the lord loves changes, it’s one of his greatest delusions” raises the question of its importance in modern times. In turn the choir’s whistling concert is sort of protesting against melody itself.

Annika Kahrs, Infra Voice, 2017, Courtesy of th artist, Image via hamburger-kunsthalle.de

The second part of the evening will be dedicated to Patrice Leconte’s short film “Le Batteur du Boléro” (trans.: “the drummer of Boléro”). The eight-minute single-shot film shows an abridged version of Maurice Ravel’s ubiquitous orchestra piece: The camera gently pans past the orchestra and finally positions itself beside the drummer, played by French actor Jacques Villeret, where it remains for the rest of the film. As the repetitive piece of music takes its course, the camera captures the agony of the drummer having to consistently play the same rhythm. Gazing at times at the camera we witness him grimacing involuntarily, his face becoming ever more distorted as he appears more and more irritated over the course of the piece.

Villeret appears more and more irritated over the course of the piece

Patrice Leconte, who always regarded Boléro as the epitome of tediousness, had the idea for the short film early in his career. After Gilles Jacob, director of the Cannes Film Festival at the time, encouraged him to finally put his idea into practice, the director set to work straight away. In return and by way of reward Jacob screened the film at Cannes in 1992 outside the competition. “Le Batteur du Boléro” is thus both an homage to actor Jacques Villeret as it is an anti-homage to Ravel’s piece.