In October’s DOUBLE FEATURE the artist Ani Schulze presents her latest film “Merchants Freely Enter”.

In Ani Schulze’s work “Merchants Freely Enter” (2017), puzzling things seem to take place yet at the same time, in the beginning it appears that nothing actually happens. High-resolution close-up shots of nature in the forest – the camera pans across a stream, leaves and mist. The forest atmosphere of the soundtrack is combined with percussive elements; intermittently the soundtrack audibly distorts, almost as if it were being broken down into its digital components. People dressed in black appear, initially visible only from the waist up, and then fully as they play with wooden birds. Now the camera takes off from the ground and flies over huge cornfields, its focus directed consistently towards the ground and never into the distance.

In this work by Ani Schulze (born in 1982), certain elements appear time and again: abandoned places, the scene-setting of architecture, the juxtaposition of written language and image, the attempt to create a visual language that communicates more than that which is merely depicted obviously. In the mixed-media installation “Vacant Lands”, the video work “Fecund Soil” (2016), for example, focuses on the surreal setting of a nature conservation area in the port area of Antwerp, directly next to one of the biggest chemical corporations in the world.

Linking up to visual habits

“From Aerial Vortices” (2015) tackles the reconstructed modernist interior of the Aubette, a classicist building in Strasbourg, which was realized at the end of the 1920s by artists of the De Stijl group. In the exhibition context, Schulze shows her films in space-consuming installations, and combines them with drawings, paintings or sculptures as can be seen, for example, at Schloss Ringenberg in the exhibition “The Crop”.

In the world of “Merchants Freely Enter”, we as observers never know exactly what we’re doing or where we find ourselves. The shots evoke specific realms of feeling, link up to certain visual habits, let the expectations subsequently aroused seemingly then come to nothing. If we wish to break down the work into various parts, we find that the structure of the first part is repeated in what follows. Instead of the close-up shots of nature though, now people lying on the ground are framed by the camera in close-up. Are they sleeping? Are they even alive? What does this have to do with the merchants the title refers to?

No one sees the same film

What’s striking is the contrast between stasis and movement: Either the static camera captures flowing movements, or it calmly glides as it films motionless objects. Although the camera almost never opens up the view to the whole picture by means of an open wide shot that would enable us to place what we see, this doesn’t result in a claustrophobic feeling of restriction. Freed of any language, either written or spoken, “Merchants Freely Enter” develops to become more and more like a kind of imagination machine, which offers itself to observers as a starting point for their own versions of the film, whereby apparently no two people see the exact same film.

As her favorite film, Ani Schulze has chosen the first part of the monumental trilogy “As Mil e Uma Noites” (Arabian Nights) by Miguel Gomes from 2015. The trilogy is loosely based on the structure of the eponymous stories from One Thousand And One Nights. In these, King Schahrayâr, disappointed by the infidelity of his first wife, takes a new wife every day, each of which he has killed after the marriage is consummated. In order to put an end to the murders, Scheherazade, the daughter of the king’s vizier, marries the king and each night tells him an incomplete story so that he must let her live another day in order to hear the end of the tale.

The director flees from the set

In “Volume 1, O Inquieto”, which translates as “the restless one”, director Miguel Gomes steps into the role of Scheherazade himself, and spends twelve months documenting everyday life and the developments in Portugal during the latest economic crisis, showing the consequences for the population. The film begins with a clash of reality and fiction – here, the closure of a shipyard with an attempt to shoot a feature film. In light of the current circumstances in his country, its unemployment and its lack of prospects, the director despairs about shooting a simple, fictional film and abruptly flees the set.

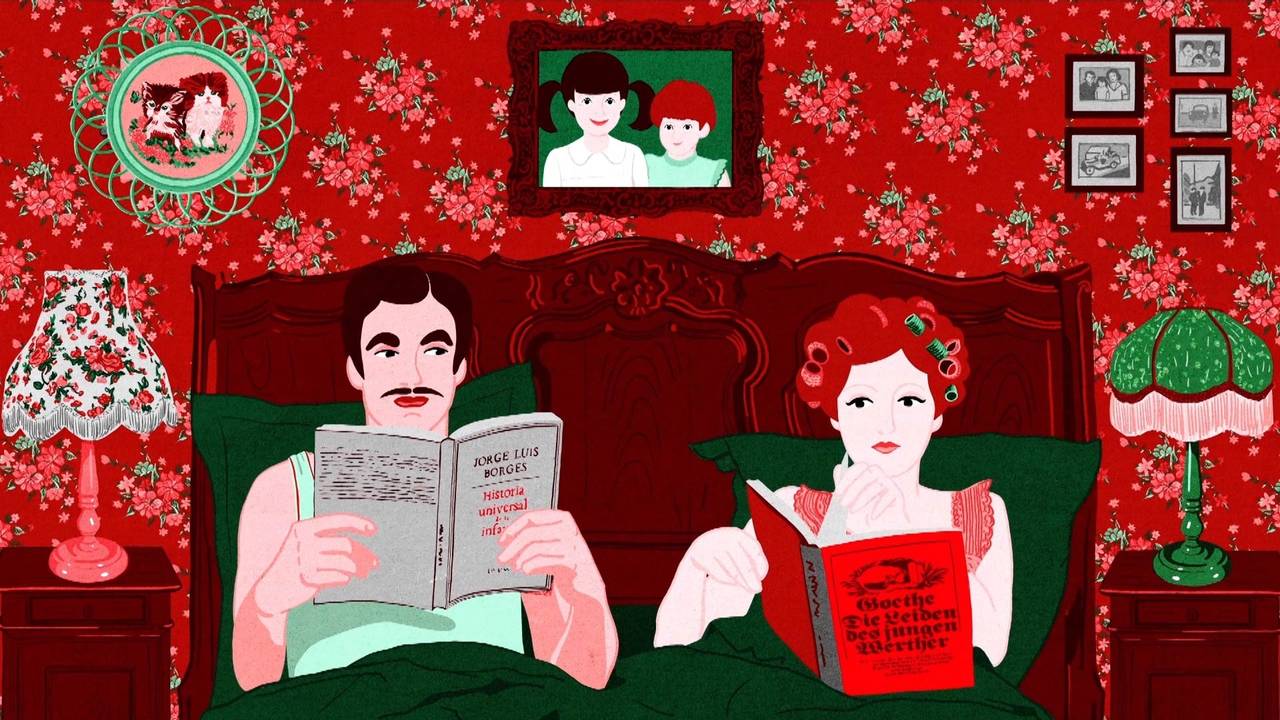

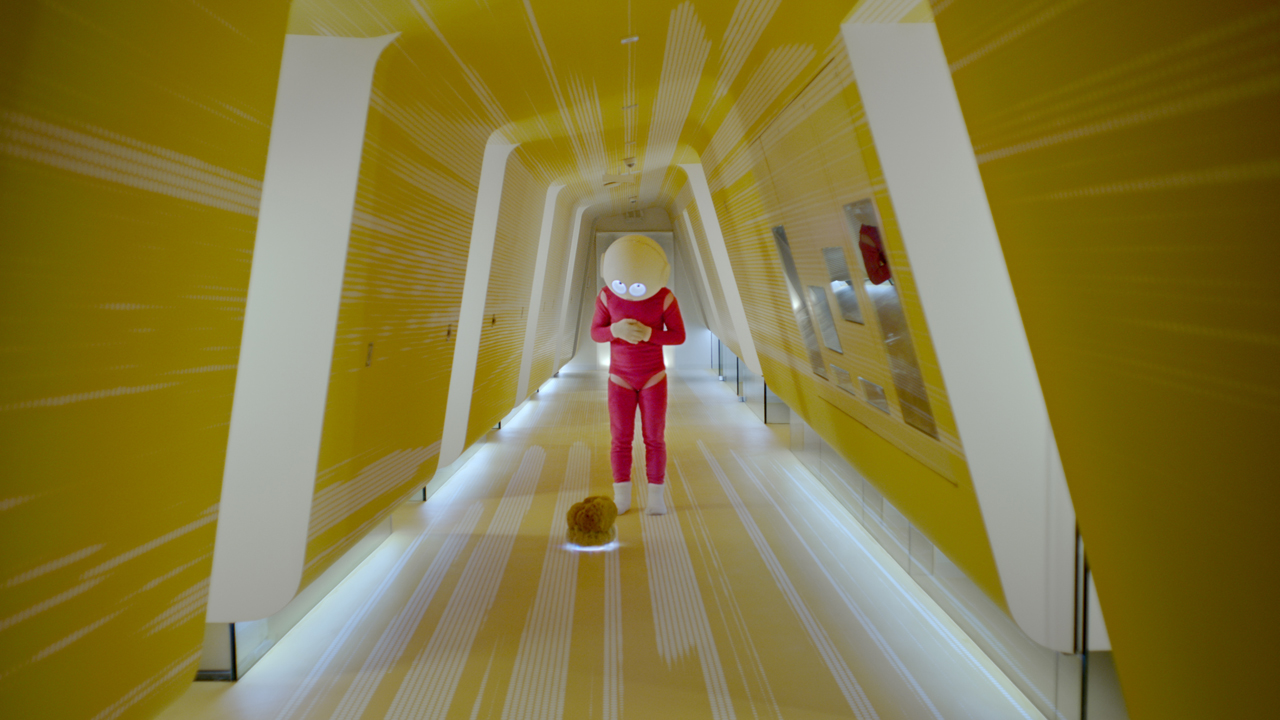

As Mil e Uma Noites, Miguel Gomes, Image via apaladewalsh.com

As Mil e Uma Noites, Miguel Gomes, Image via shifter.pt

The crew captures Gomes and threatens to kill him, and it is thus that he begins to tell stories, as Scheherazade did: stories about a meeting between the Prime Minister, the Finance Minister and trade union bosses and their permanent erections, triggered by the spray of a cheeky shaman. Stories about a (real) court case concerning a rooster, which woke up the neighbors far too early every day with its cry and hence was condemned to death. And tales by and about simple people who have lost their jobs and now eek out an existence on the poverty line.

The monumental and the megalomaniac

The film tells “stories of rich and poor, of the powerful and the unknown, of young and old, of people and animals”, according to Miguel Gomes. The work is reminiscent of a film essay, and is simultaneously playful, serious, fleet-footed, dramatic and above all, extremely human. Gomes attempts to pack the breadth of human emotions into stories and images and to explore the metaphorical potential of events that are independent of one another. At the same time, the film represents an attempt to delve into social, political and historic events with explicit topicality and specificity. Based on its form, the monumental and perhaps indeed the megalomaniac nature of “As Mil e Uma Noites” also always harbors something of that which the specific individual who loses his job, his property or his great love here must feel towards the happenings in the world: sometimes left behind, sometimes amused, sometimes sad, sometimes grotesque.

As Mil e Uma Noites, Miguel Gomes, Image via revistainterludio.com.br

At the mercy of waiting

Artist Bani Abidi is dedicated to the dark absurdities of everyday life. In her video work "The Distance from Here" bureaucracy takes over and waiting...

“Please don’t make a film about Godard!”

A film about filmmaking sounds a bit meta. But Kristina Kilian’s video work takes us on a ghostly journey through Godard’s Germany after the fall of...

Black is not a Color

In a film series, Oliver Hardt combines the themes from Kara Walker’s work with the perspectives of Black people in Germany. In conversation with...

How do we Remember?

In which places does history become visible? And what do we remember at all? Maya Schweizer begins her search for clues in the sewers and slowly feels...

Film highlights from South and North America

How can we break with the power relations of the past and create a decolonial future? A look at the representation of Indigenous women in film.

Must See: The World of Gilbert & George

Eccentric, fascinating, repulsive, entertaining and full of symbols: “The World of Gilbert & George” is a collage about the artifice of everyday life...

Spring is coming, and so is Magnetic North

For the first time in Germany, principal works from Canada’s major collections are on view at the SCHIRN. At the same time, the exhibition examines...

A Revolution in Iranian Dance

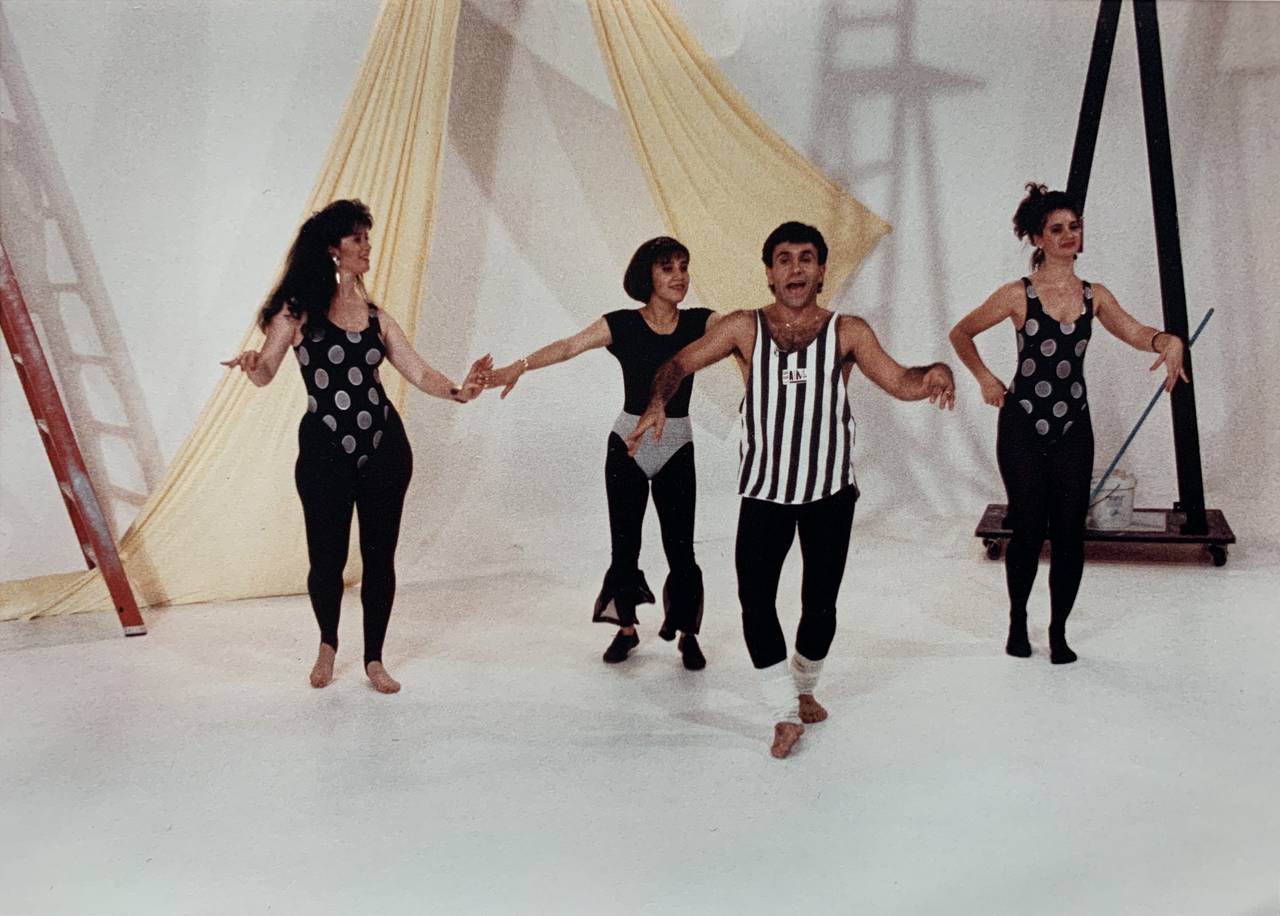

After the Iranian Revolution a nationwide dance ban was issued. It was subverted by smuggled video cassettes of dancer-in-exile Mohammad Khordadian,...

How to perform painting

This is perhaps the best way to describe the work of video artist Angel Vergara: Art history meets pop culture, the artist himself appears as a...

About the resistance of our bodies

Hypnotic dances and hybrid beings in cyberspace: Video artist Johanna Bruckner transforms the human body into digital matter.

More than a Honeypot

Young, beautiful and dangerous: the prototype of the Bond Girl still shapes the cliché of spies. Author Chloé Aeberhardt on the reality of espionage...

How to create the unexpected

About life in exile, anarchic art, and the “black milk” of the earth: The art historian Media Farzin met her old friends Ramin and Rokni Haerizadeh...

Why so cryptic?

What lies behind the title of the exhibition by Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian. And why humor is sometimes the best criticism....

Schirn Preview: Ramin Haerizadeh, Rokni Haerizadeh and Hesam Rahmanian

Exuberant, funny, eccentric and full of allusions: The Schirn presents the Iranian artist collective's first solo exhibition in Germany.

The Future of Video Art

Six international video artists present their new works. An exchange about new trends and forms of expression in film.