Cuteness overload! Bambi is a recurring reference in COSIMA VON BONIN'S visual world. But such a saccharine appearance can be deceptive. What are the downsides of cuteness, and where are there dangers lurking?

I don’t know about you, but when I think of Bambi I immediately picture his clumsy first attempts at walking. The way he first stands up full of confidence and curiosity, boldly stretching his thin little legs, and then collapses again with a mixture of surprise and disappointment. His uncertainty grows, his ears go back, and he looks at us spectators with his big doe eyes, as if asking for leniency.

To make sure I didn’t get anything wrong here, I watched the scene again – and what can I say? Cuteness overload! “Oh my! Well look! Well isn’t he cute?” say the animals when they see the newborn fawn, vocalizing exactly what you yourself are thinking – or rather feeling – when you’re watching it. The other animals in the forest call him “little prince”, “young prince”, or simply “little one”. Awwww! The scene is almost a lesson in cuteness: Bambi is needy and vulnerable and thus inevitably prompts instincts of care and protection, while likewise promising innocence and guilelessness. He is free of greed, cynicism, anger, hatred, or violence – all in all, a rather idealized depiction of cuteness.

The power dynamics of cuteness

Bambi is a recurring point of reference in Cosima von Bonin’s visual world. From him as a figure, she abstracts and extracts individual gestures of cuteness and dissects their complexity, particularly with regard to their role in interpersonal relationships. After all, the animals in “Bambi” are anthropomorphized; they actually stand for human characteristics and emotions. In the textile image “Upstairs Downstairs”, we see one transparent and one black silhouette of Bambi, complete with his awkward, wobbly legs. In exposing his insecure state and associated helplessness, Cosima von Bonin draws attention to the flipside of cuteness, which Daniel Harris described as follows in his much-quoted 1992 essay “Cuteness”: “Cuteness, in short, is not something we find in our children but something we do to them.” Cuteness is not always a quality, but can also be an attribution. As an attribution, however, it becomes a sadistic act, a disempowering gesture. And infantilization always goes hand in hand with the narcissistic desire to feel superior.

Cuteness, in short, is not something we find in our children but something we do to them.

That said, the power dynamics of cuteness are even more complex. The image could also be read as an allusion to the most famous scene in the movie, namely the death of Bambi’s mother. Is Bambi standing here, startled by the hunters’ first shot, at the winter feeding ground? Either way, it is the key moment in the film, which also signals the end of Bambi’s cuteness. When it becomes clear that his mother has died, the fear arises that Bambi’s vulnerability, his neediness, could have been responsible. And suddenly the question is turned on its head: How much cuteness and thus vulnerability can I actually expect others to accept? How dangerous can cuteness – in the sense of self-infantilization – be even if it is unintentional?

Cuteness and manipulation

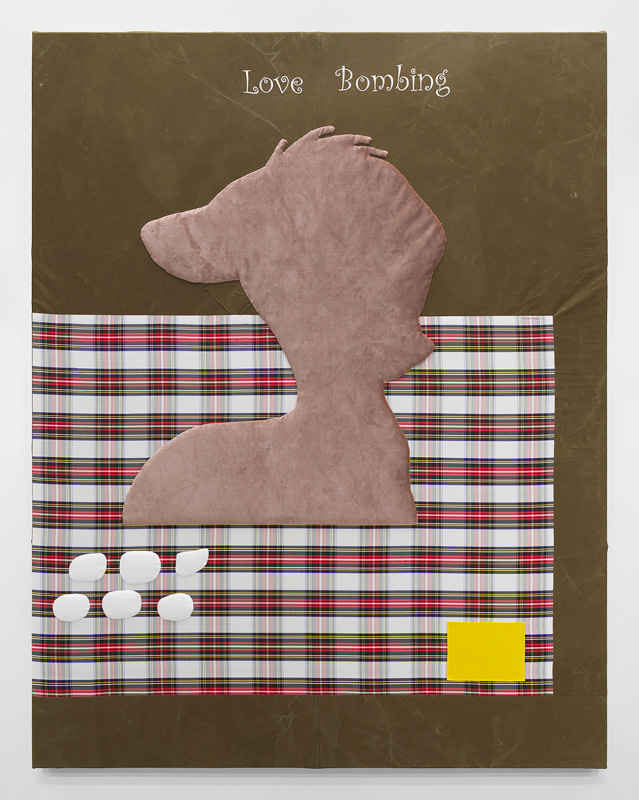

Cosima von Bonin describes a similar twist to cuteness and innocence in her two works “Love Bombing” and “Gaslighting”, too, which are likewise textile images. In “Love Bombing” we see Bambi, who can be easily recognized with his fuzzy little forelock, and in “Gaslighting” his girlfriend Faline. In the film, the pair’s relationship serves as an idealized depiction of growing up together, from childhood friendship to a romantic relationship through to starting a family. With the titles of these works, which also appear in the images as lettering, Cosima von Bonin questions such normative notions of relationships. A strong protective instinct and excessive affection is not always desirable. It can also be overbearing or threatening – as, for example, in the sense of “love bombing”, when someone uses manipulative tactics to emotionally abuse their counterpart in order to quickly gain their trust and thereby achieve a personal objective of some kind.

Cosima von Bonin, LOVE BOMBING, 2023, Image via petzel.com

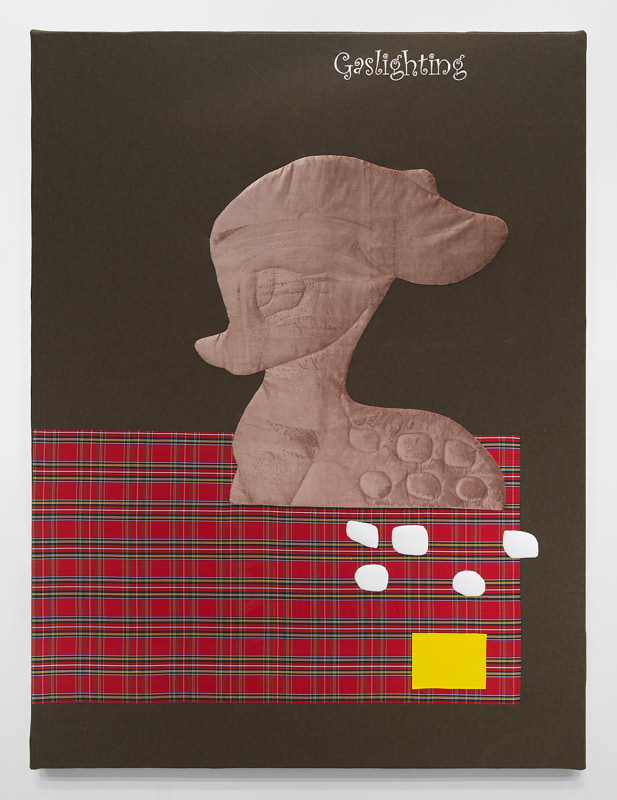

Meanwhile, a supposedly understanding conversation between close partners may also conceal “gaslighting”, a form of psychological abuse when information is systematically distorted in order to challenge the other person’s ability to perceive things.

Cosima von Bonin’s protagonists have forfeited their cuteness not only aesthetically but also emotionally – and that goes even for the cutest of them all, Bambi. On the one hand, it’s a little sad, because these are characters that shaped many a childhood, because the characters embodied qualities that we once emulated, which we found to be cool or (in their weaknesses) cute and lovable. When Cosima von Bonin confines the Bugs Bunny character to the trashcan, with him goes the cunning behavior of which he was also capable. If you watch the Looney Tunes episodes more closely, then you might well be inclined to accuse the cute bunny of “blame shifting” here and there, as the title suggests.

Cosima von Bonin, Gaslighting, 2023, Image via petzel.com

The works by Cosima von Bonin never really make it clear to us what she thinks of her references. Is this a critique of the normative notions of gender and relationships forced down our throats in Disney films and Warner Bros productions? Is it a demystification of commodified representations of love, friendship, and kindness? The fact that she uses the Curlz font for “Love Bombing” and “Gaslighting” – and thus alludes to “crappy design” – in turn underscores that these critical comments themselves as commodified and useless. Might it even be understood as a critique of an overly psychologized present, where discourses that are actually meant to make us aware of something have in turn become instruments of power? These questions cannot be answered, but Cosima von Bonin’s works provide an opportunity to explore these attitudes and think through the tipping points in complex power relationships in more detail.