Many of the teaching staff at the Casablanca Art School contributed to the journal “Souffles”, an extraordinary example for the strong interrelationship between modern Arab art and journalism. That said, it was by no means the only journal of its day where this applied.

During his time studying in Europe in the 1950s and 1960s, Mohamed Melehi not only developed an enthusiasm for Bauhaus but was also fascinated by a collective practice that the young artists in leftist-progressive circles considered a natural element of how they saw themselves as artists, namely founding magazines and journals. These publications stood out for their transgressive character: They brought architects together with painters and poets and sculptors, and they closely and inseparably linked aesthetics and theory. Melehi was soon driven by the wish to set up a journal himself. In 1965, only about half a year into his time as a lecturer at the Casablanca Art School, an opportunity arose, and he seized it. At an exhibition of his works in Rabat he was approached by young poet Abdellatif Laâbi who asked him whether he could imagine designing the cover page for a new journal. Melehi didn’t need to be asked twice: “I immediately pricked up my ears when I heard the word ‘journal’! I immediately said yes, I’m interested. But there’s no need to pay me, instead just let me be part of the undertaking.” (1)

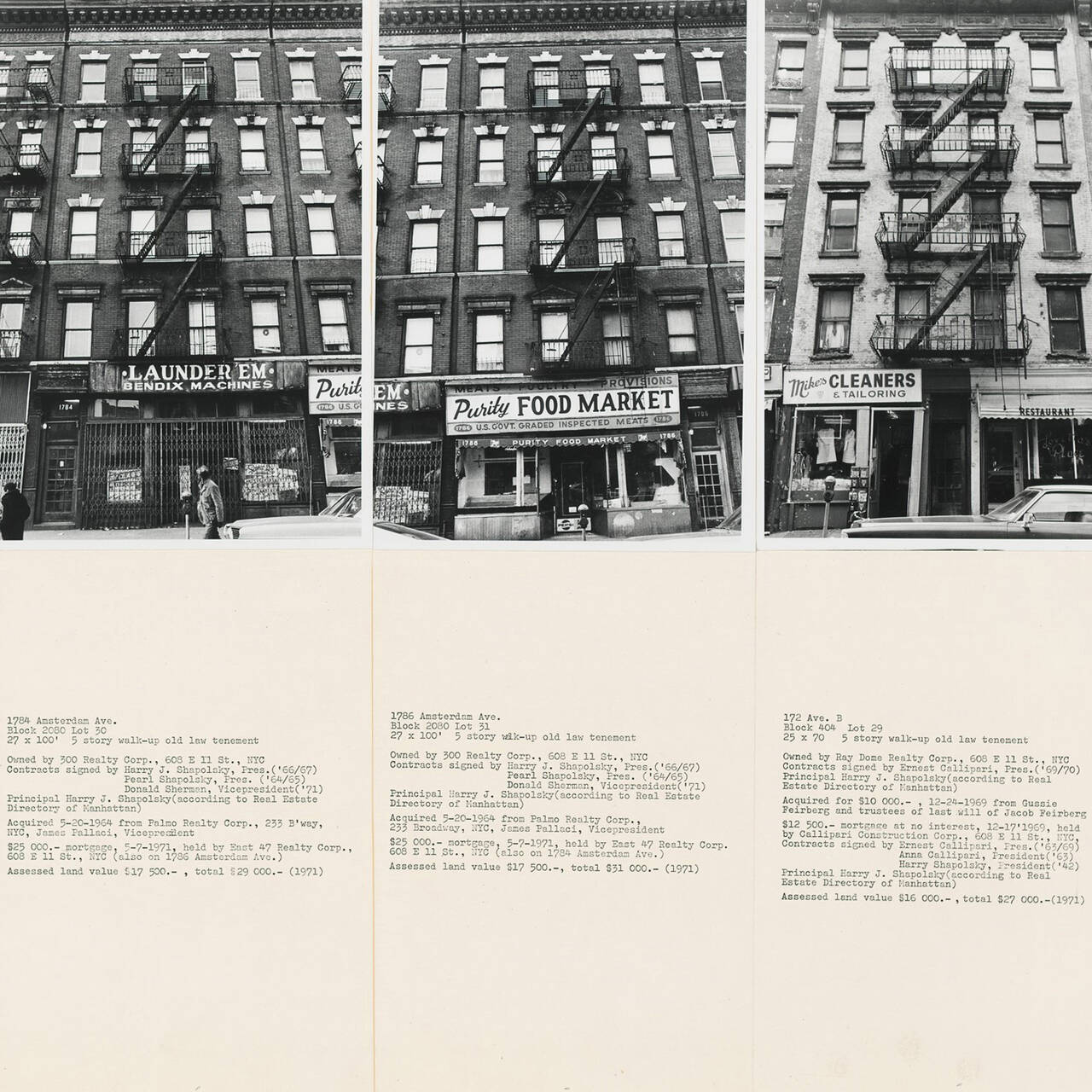

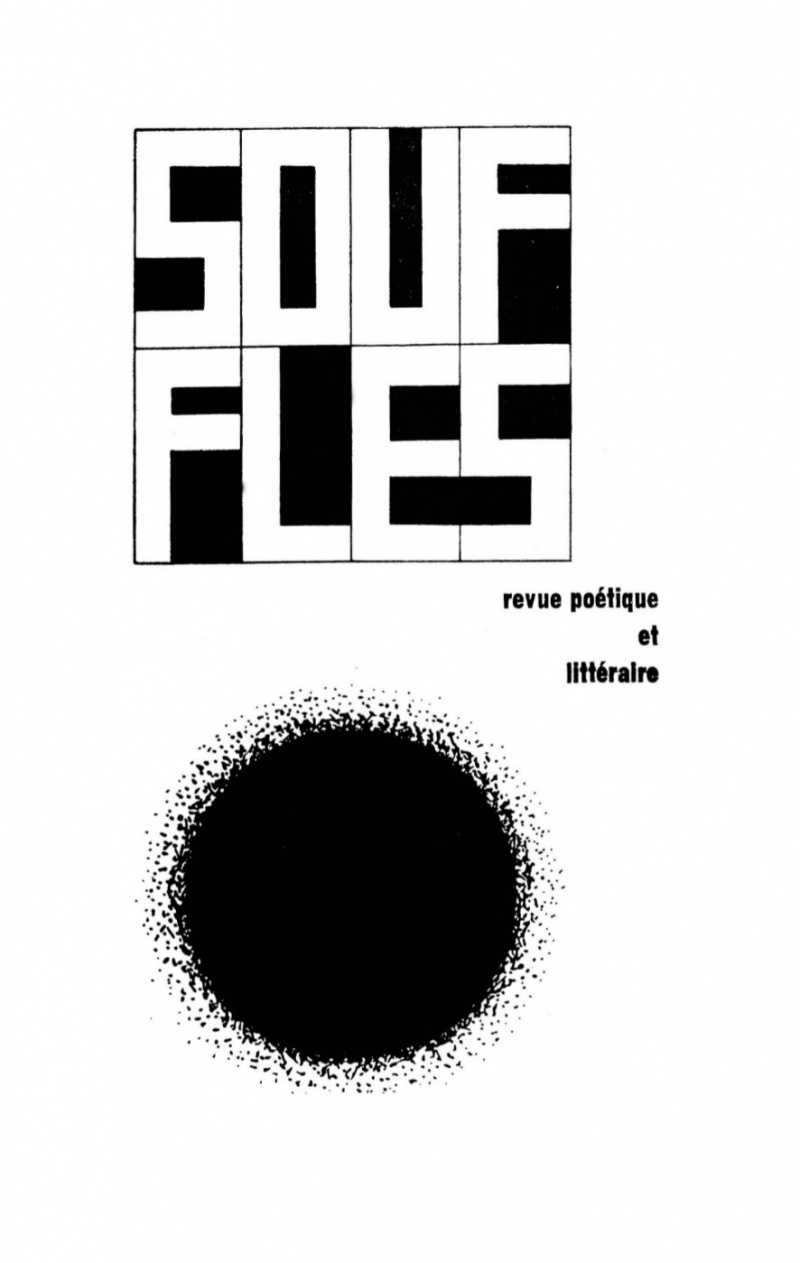

Souffles 1, 1966, Image via monoskop.org

It is moments like this that gave rise to journals being founded. The first issue appeared in March 1966; Melehi designed the cover, which boasted the iconic circle with its porous edges: someone breathing onto a cold pane of glass. “Souffles” (Breaths, 1966–73) was from its very first breath onwards a declaration of war against France’s civilizing mission (mission civilisatrice) and its postcolonial shadow, but also against a national cultural policy that lay ossified in exoticism and folklore. The editorial teams consisting of authors, fine artists, critics, and filmmakers all sought to realize a Moroccan Modernism in all realms of the country’s culture. Unlike the “Lamalif” literary magazine founded that same year and “decidedly tamer” (2) “Souffles” was firmly in keeping with the protests of the day on Morocco’s streets and proclaimed the young nation’s “cultural decolonization” décolonisation culturelle).

“Souffles” – both studio and gallery

By the time the first few issues had appeared, the artists from Casablanca stepped out of the shadow of the authors with all their persuasive words: Between 1967 and 1971, it was the artists who primarily influenced the discourse in and shape of the journal and redefined the relationship between the medium and the fine arts – to an extent that far outstripped anything attempted by any other publication in the Arab world at that time.

“Souffles” was, to quote Katarzyna Pieprzak, a “discursive museum” in which politics became the object of art and art the object of politics. (3) There, calligraphy and poster art became the prime forms of an art that was as Modernist as it was revolutionary and addressed not the art cognoscenti but a mass audience. (4) For the artists from Casablanca, the magazine was both studio and gallery. It was a means to transport ideas and thus enabled them to subvert an art market dominated by Europe and establish alternative networks in the Global South. And it was a public platform on which in their role as intellectuals they were able to intervene in the social debates of the times. One thing “Souffles” most definitely was not: a journal by artists who laid claim to sole sovereignty in the field of art.

Composition with covers of the Souffles magazines (1966-1971), Image via museoreinasofia.es

Instead, it is an extraordinary example for the profound interaction between modern Arab art and journalism, although it was by no means the only journal of its day to which this all applied. The 1960s were a decade that saw much agitation in North Africa and the Middle East, and during which the tone of the revolutionary rhetoric of emancipation grew sharper. The ‘Third World’ became the chamber of solidarity among the former colonial states in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Arab nationalism with a socialist thrust, and Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser gave it a charismatic face, electrified a trans-Arab generation. After the Six Days War of 1967, which ended in disaster for the Arab states, the Palestinian resistance struggle took on this leading role, which ‘Souffles’ editors also supported in word and deed.

Arab journals straddling literature and art

In other intellectual centers of the Arab world, such as Beirut or Baghdad, literature and the fine arts closed ranks in both theory and practice: in salons, galleries, and above all on journal editorial desks close collaborations between the two forms of art were no longer an exception.

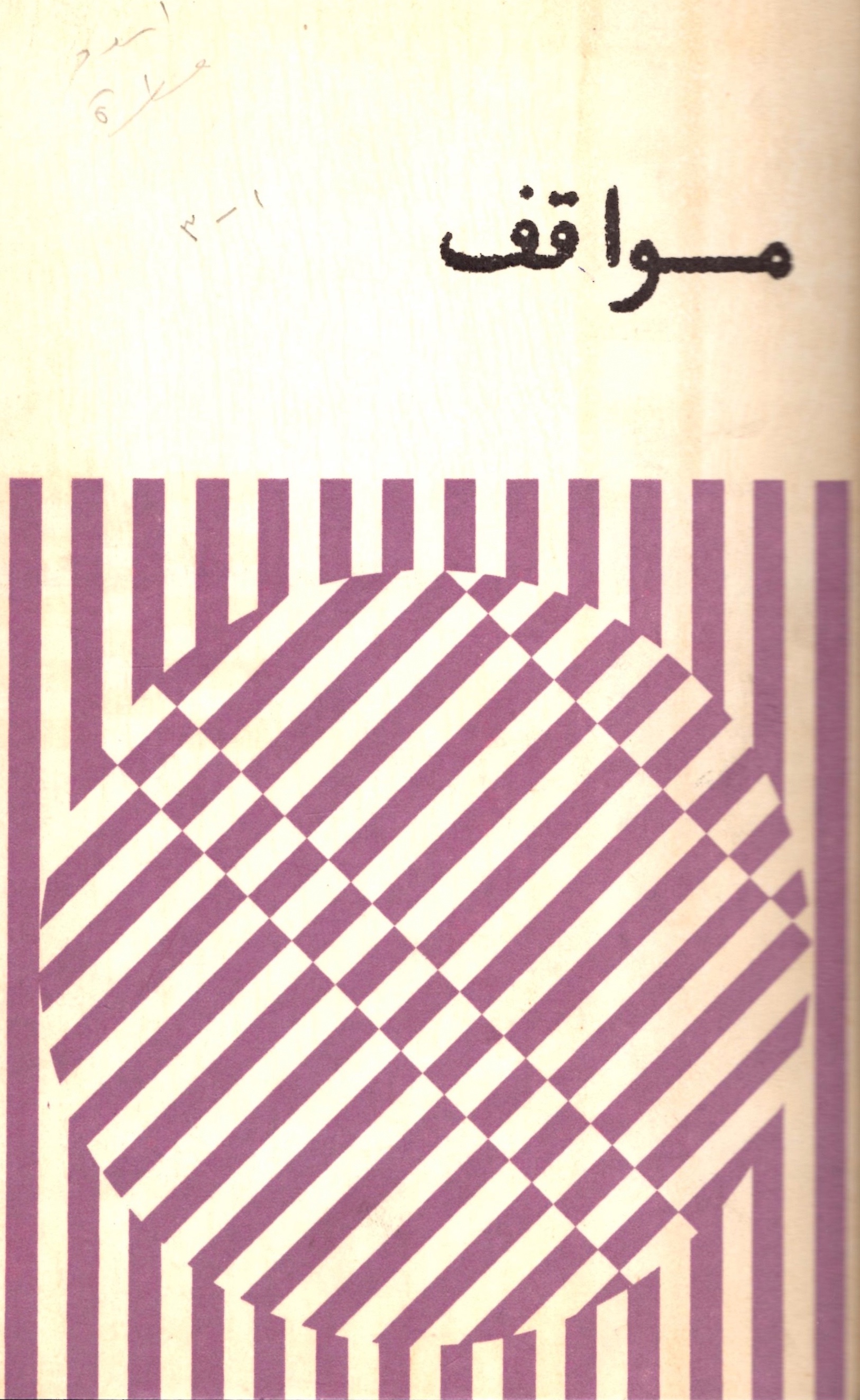

One of them had been established by Syrian poet Adonis, namely the Beirut journal “Mawaqif” (Positions, 1968-1994); politically close to “Souffles”, the journal had prominent members for example in Palestinian painter Kamal Boullata, Jordanian sculptor Mona Saudi, and Lebanese painter Maler Samir Sayegh. (5) That said, even in those publications that still defended liberal values and an aesthetic of autonomous art, and the West was not seen purely as an enemy, relations between the arts became more intense: The editorial meetings of poetry journal “Shi’r” (Poetry, 1957–70) brought together Modernist Beirutpoets and painters; and “Hiwar” (Dialog, 1962–7), which likewise came out in Beirut, for the first time granted Modernist art an equal place alongside literary texts instead of treating it as mere illustration, as had hitherto been the case. (6)

Mawaqif 1, 1968, Image via eurozine.com

In the course of the Cold War, the question what role the arts would play in progress in Arab societies became the issue that decided one’s ideological position. However, the question was itself not new and had from the very outset been debated in journals. From the late 19th century onward, journals such as Egypt’s “al-Muqtataf” (The Selection, 1887–1952) discussed how Europe’s ‘beaux arts’ and the related processes and forms such as oil painting, portraiture, sculpture, and later photography, film, and abstract art could be brought into harmony with local aesthetic traditions. (7) The intention was not only to familiarize Arab readers with Modernist techniques and new literary forms, such as the novel, but through the medium of the journals also learn Modernist ways of seeing. (8)

The End of “Souffles”

Artistic avant-gardes and intellectual journals are similar in many respects: Frequently they start with a strong group ethos and just as frequently end in vitriolic argument; ruptures and divisions. “Souffles” is no exception in this regard.

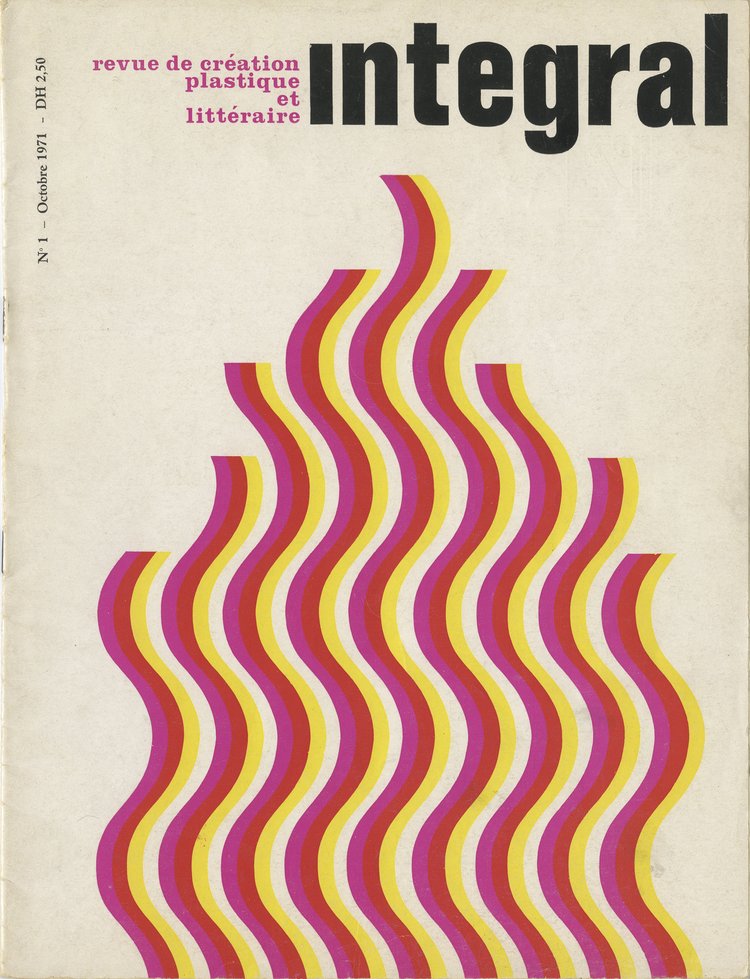

In 1971, its sister journal “Anfas”, published in Arabic, was established with its own editorial board and a focus on political and social themes in the Arab world. The original French edition also changed fundamentally when Abraham Serfaty joined the editorial team as under his influence “Souffles” became the publication mouthpiece for Morocco’s Marxist-Leninist opposition. This development led eventually to “Souffles/Anfas” enforced end: In January 1972, Laâbi and Serfaty were both sentenced to several years imprisonment. The violent repression and persecution of the leftist political opposition during the rule of King Hassan II. Between the 1960s and 1980s reached their highpoint at this time. With the exception of Chabâa, Casablanca’s artists had one year earlier, as it became clear that art and literature would henceforth play only a subordinate role in “Souffles” quit the editorial board. Melehi and Nissabouri pursued their original intentions from 1971 onwards in a new journal: “Intégral” (1971–7) made it clear with the cover of its very first issue (the wave-shaped graphic that Melehi had contributed in 1969 to the Plaestine issue) that it was taking up the former joint project which “Souffles” had now definitely left behind it. Like many journals of this generation, it was the result of an extraordinary friendship between artists, but also a document attesting to their estrangement.

Cover of the magazine Intégral, n°1, October 1971. Design by Mohamed Melehi. Mohamed Melehi Estate., image via qm.org.qa