The CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL revolutionized the Moroccan art scene and managed to liberate itself from its French colonial past. In some respects, it took its cue from the Bauhaus. So what do the C.A.S. and Bauhaus have in common?

In 1919, the “École Municipale des Beaux-Arts” or School of Fine Arts in Casablanca was founded during the days of the French Protectorate. The curriculum corresponded to European ideas as the prevailing view then was that European culture was qualitatively superior to the stylistic currents of the Global South. Arts from Morocco were considered as being “decorative”, “folklorist” and “inferior”. Moreover, the “fine” arts were preferred to the “applied” arts.

Casablanca Art School bulletin, 1965, Image via bauhaus-imaginista.org

Mohamed Melehi (left) in his studio in Casablanca with Mohammed Chabâa, Photo: © M. Melehi Archiv/Nachlass, Image via christies.com

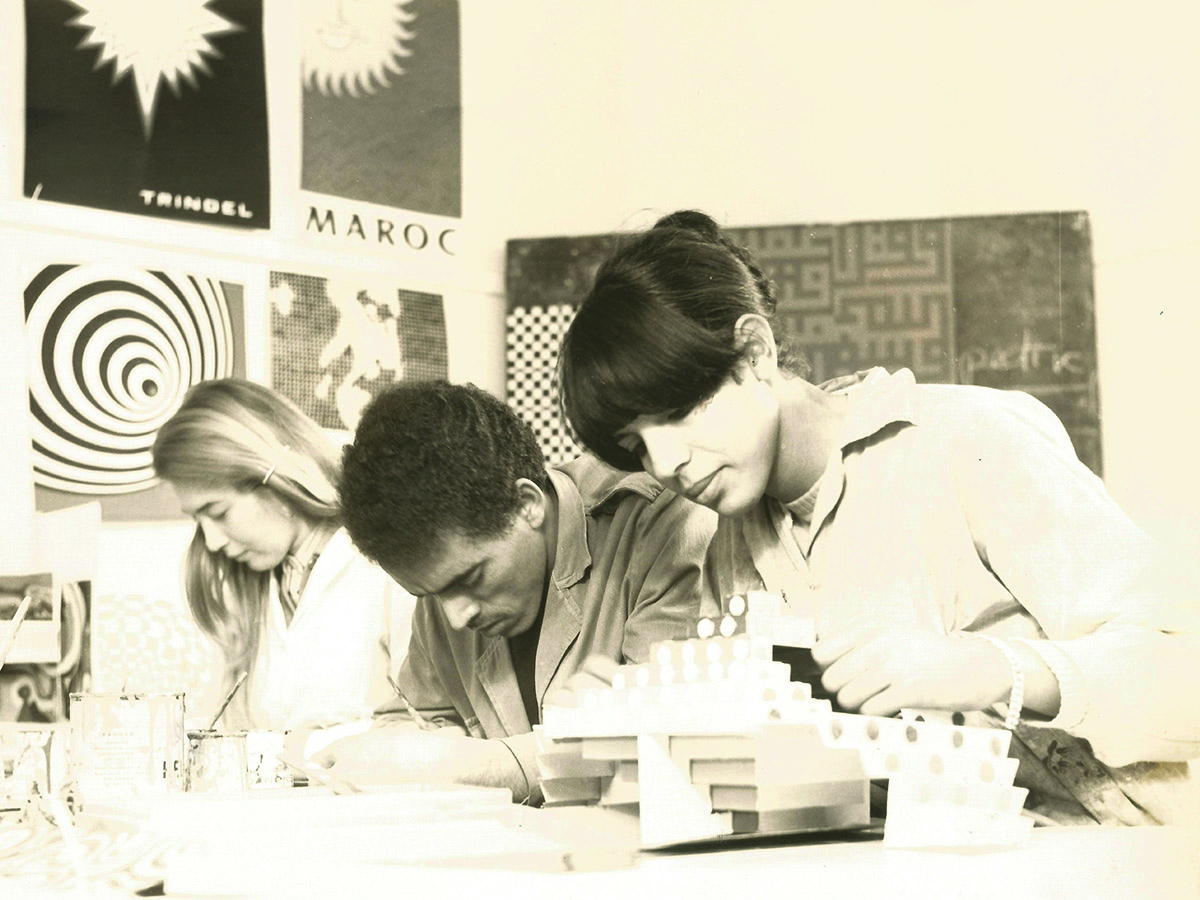

However, in the wake of Morocco’s independence, the school was reformed by young artists in the early 1960s. Artist Farid Belkahia was appointed the new director in 1962. He was joined by lecturers Mohamed Melehi, Toni Maraini, Bert Flint, and Mohammed Chabâa. All of them were familiar with the Western art canon, had traveled and studied in the United State or in Europe. Their shared vision of establishing an international, decolonized and democratic college structure and culture is readily apparent from the new name they chose for the institution: the “Casablanca Art School”.

UNIQUE PICTORIAL LANGUAGE AND DECOLONIZATION

Precisely after the end of French colonial rule, the country’s national identity and its awareness of its own cultural heritage needed reinforcing. For this reason, the lecturers sought for local and self-determined forms of expression and declared Morocco’s iconographical heritage to be part of the new teaching program. Thus, the students went on regular excursions to historical sites to learn more about traditional urban and rural architecture as well as arts and crafts. Lecturers such as Mohamed Chabâa concerned themselves with Arab calligraphy and combined it with painting and artisanal skills. For the first time in Morocco, under Toni Maraini as Director of Art History, the program also addressed art production in the country and outside the Western canon. Henceforth, it was no longer to be a Baroque chair or a Gothic church in France that was to be the role model, but sources in the region. The school sought inspiration in the local past and developed an open, light-touched, and poetic approach to Moroccan history.

The extensive “bauhaus imaginista” research project in 2018–20 was devoted to the history of the reception of the Bauhaus and shows how its influences extend as far as the Casablanca Art School. For although the Casablanca Art School pursues its very own political agenda, it has adopted aspects of Bauhaus teaching: its own style history serves as a kind of source that encourages and leads above all to modern creative forms. The Bauhaus was defined by a similar approach, albeit without the strong local focus. For example, Bauhaus master Paul Klee in 1927 took his cue from a rural knotted carpet from the Arab space. He represented the historical fabric in his own way and linked the ancient to his own abstract formal idiom.

THE CASABLANCA ART SCHOOL AND THE BAUHAUS

The Bauhaus founding manifesto of 1919 uses a Lyonel Feininger woodcut of a cathedral to visualize the ideal of a Medieval construction cabin in which all the different trades coexisted under one and the same roof. However, the idea is represented in an Expressionist vein, all hard edges and coarsely carved. Instead of the Expressionist formal idiom and the charged, almost religious rhetoric of the early 1920s, from the 1960s onwards Casablanca Art School pursued an agenda intended to modernize the local heritage. Drawing on the Moroccan tradition of art and directly referencing the Bauhaus, the school set out to review the relations between “art”, crafts, design, and architecture.

Former Haus Sommerfeld, Berlin. Architecture: Walter Gropius andAdolf Meyer, 1920–1922, Photo: Carl Rogge, Image via wikipedia.org

Ansicht der Ausstellung „Présence Plastique” von Farid Belkahia und seinen Kolleg*innen in Casablanca (und zuvor in Marrakesch), 1969, Foto M. Melehi. © M. Melehi Archiv/Nachlass, image via christies.com

In the workshops, the Bauhaus students joined up with the “form masters” and “works masters” to test approaches to materials and techniques. In this way, among others, buildings such as Haus Sommerfeld arose: There, many students from the different workshops together worked on one and the same project. On another occasion, the students joined forces to produce magazines and journals. In them, they presented graduation projects, and published texts and photographs. The various issues attest to a great zest for experimentation and formed a platform for political discussions.

PARTICIPATION AND COMMUNITY

The Casablanca Art School ran comparable (albeit not identical) projects destined to foster participation and community, and to challenge the traditional divisions between the genres. Starting with the traveling exhibition entitled “Présence Plastique”, where the students and teachers took their art out into the public realm of the city, and on to the Asilah Moussem cultural festival, which stood out among other things for communal, large-format wall pieces in part designed together with village inhabitants, through to the “Souffles” magazine to which the teachers at the Casablanca Art School contributed as authors and illustrators. Here, editorial choices and decisions on content mingled with design. The aesthetic program translated the political contributions into art practice. Mohamed Melehi, Director of Painting and Photography, developed the cover design, while Chabâa designed the logo, and Toni Maraini contributed texts. The magazine presented literary positions from a transnational network as well as from the Maghreb. One special focus was on the local pictorial vocabulary and on Islamic architecture, jewelry, textiles, and popular art. The magazine created a wealth of visual material and offered a theoretical superstructure from the period prior to colonial oppression. The fact that, for example, famous theorist Frantz Fanon presented ideas in the context of the journal rounded out its vision of laying the foundations for a collective and postcolonial identity.

The Casablanca Art School learnt from the Bauhaus to unlearn the past and rethink things. Testimony to this is not least the writings that Mohamed Melehi and Toni Maraini penned during their time at the Casablanca Art School. Melehi thus wrote in his “Memoirs” of 1964: “The approach Bauhaus took helped to forge a bridge between the Western Modernist movement and our own vision of modern art in Morocco, even if here there was no long tradition of Classical European figurative representation. The Moroccan artists were familiar with the different art historical epochs, yet it was only the Bauhaus that could reconcile us with our own tradition in art, with its decidedly creative refinement.”

It is no doubt that it was reconciliation as was driven by the Bauhaus which encouraged the artists of the Casablanca Art School to develop a style very much of their own and champion a decolonial consideration of their own culture.

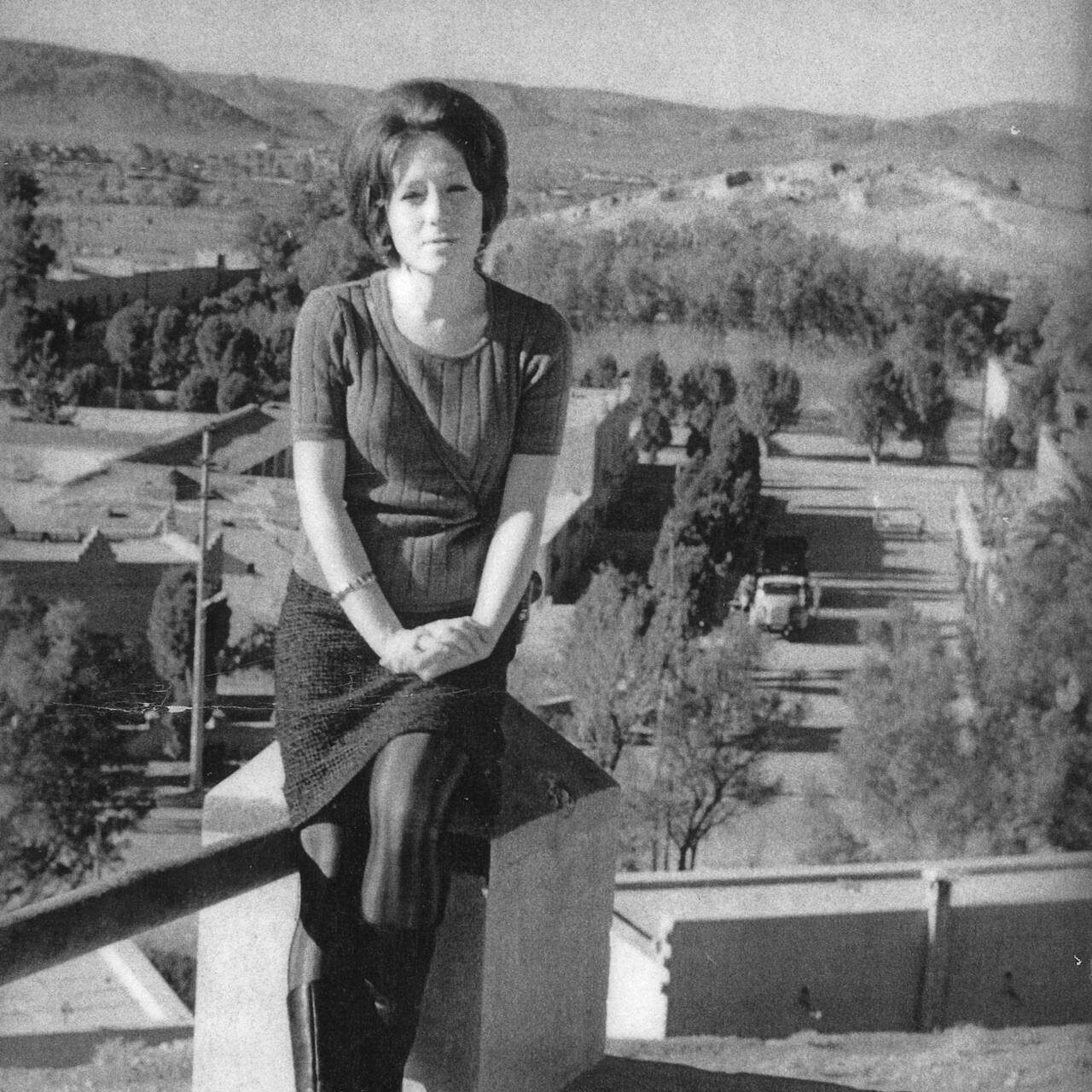

Students of the Casablanca Art School, image via mosaicrooms.org