What happens when algorithms endanger human life? Video artist Helen Knowles addresses the responsibility of artificial intelligence.

In recent years numerous ethical discussions emerged around so-called artificial intelligence, technical singularity and humanoids, contemplating various future models, some more and some less apocalyptic. Meanwhile, global market-listed companies from are implementing the self-learning algorithms in real life, be it for credit applications, marketing evaluations, or by means of the much-maligned Twitter and other social media bots.

Consultancy company PricewaterhouseCoopers (pwc) predicts that AI technology will boost German GDP by 11.3% by 2030, while the American Society for Human Resource Management was already reporting last year that legal representatives of major corporations, which are increasingly relying on AI for application and employee assessment procedures, are already preparing for class action lawsuits relating to this.

While only last year an EU expert committee addressed the question of what exactly ethical use of artificial intelligence should look like, British artist Helen Knowles was already examining the very specific problems that might arise with her video work “The Trial of Superdebthunterbot” in 2016. The film lasts a good 45 minutes and is based on a performance that the artist gave as part of an exhibition opening at the Oriel Sycarth Gallery in Wrexham, UK. The basic premise of the work is that the AI “Superdebthunterbot” has to defend itself against a manslaughter charge in court proceedings.

On behalf of a company that has bought up repayable student loans from the British government, the computer finds dubious job offers for the debtors as a way to get them to pay up. The AI arranged for two of the debtors to take part in a medical trial, where they subsequently died from side-effects. So is the “Superdebthunterbot” now guilty of manslaughter? Should it have checked the medical trial for its legitimacy? The artist asked lawyers Oana Labontu Radu and Laurie Elks to compose pleas and to present them before an audience, which was then to give its verdict as a jury.

Three cameras, one drone, and a head-mounted GoPro captured the action

Helen Knowles, who shines a light specifically on the distribution principles of the financial economy with her extensive multimedia installation “Trickle Down, A New Vertical Sovereignty” at London’s arebyte Gallery, produced a video version of the performance in 2016, which was filmed at London’s Southwark Crown Court. Three cameras, one drone, and a head-mounted GoPro captured the action. To the ominous sound of strings, a court employee pushes an unprepossessing computer in a glass case along a long corridor to the courtroom.

The jurors are briefed by another employee on how exactly they must behave in the court. Before the prosecution and the defense give their pleas, the judge (played by actor Mark Frost) first summarizes the lines of argument once again and makes it clear that it is the artificial intelligence and not the programmers who are on trial. Subsequently, the camera follows the jury as they debate their verdict – the discussion hinges on certain questions that the court has posed to them: Can we assign guilt to AI? Does it act consciously? Does it have a duty of care to the debtors? The jurors are at odds: One woman wishes to blame the AI solely in order to send a signal to companies who use self-learning computers.

Can a machine want what it wants?

Others deny AI has freedom of action and thus deny guilt per se. You can sense how the questions in this fictional case and their implications break new ground in relation to reality: What is the appropriate way to deal with machines that act as digital brokers and thus directly influence the global economy, or can effect the dismissal of employees through their involvement in staff appraisals within companies? Does the AI perhaps have similar problems to its creators, human beings, who – according to Schopenhauer – cannot will what they want?

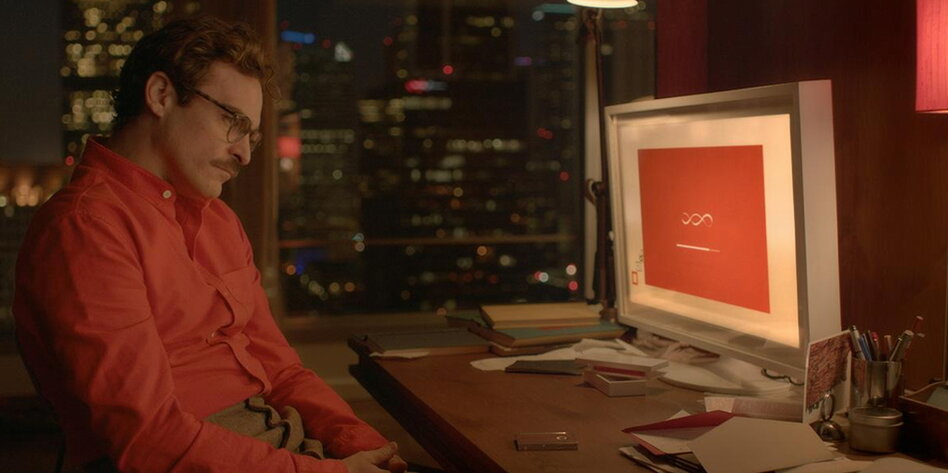

Similar questions might also be brought to mind by Spike Jonze’s film “Her” (2013), which Helen Knowles has chosen as the second film for the Double Feature. The film can perhaps best be described as a kind of sci-fi romance. In a not-too-distant future Theodore Twombly (Joaquin Phoenix) works for a service provider that composes letters of any kind – greetings cards and thank-you letters, love letters or messages of condolence – for clients who cannot themselves find the right words.

A romantic relationship is developing between Theodore and AI Samantha

In his spacious office bathed in warm light, Twombly dictates touching messages to his computer day after day, while his own private life is in tatters: His marriage of many years is ending, but his loneliness and disillusionment prevent him from signing the divorce papers. When eventually the new, entirely speech-controlled operating system OS 1 is introduced, a love story gradually builds between Theodore and the system’s AI Samantha (Scarlett Johansson).

Spike Jonze, Her, 2013, Film still, Image via taz.de

Spike Jonze’s film cares little about the major technical or overall social implications that go hand in hand with the creation of artificial intelligence. Rather, it stays with the individual, whose loneliness and longing for love under changed auspices form the focus of the film. Theodore Twombly is amazed by how solely verbal interaction can captivate him and enrich his life, yet he has no possibility of even touching the object of his affections.

All other senses are increasingly losing their significance

The physical sensation of a romantic relationship is thus shifted as close to the brain as it could possibly be: Only through the ear – the nearest organ to the human control center – can the partner be perceived, meaning all other senses increasingly lose their significance. In Helen Knowles’ work, artificial intelligence resolves this problem in an entirely different way: Its lack of physicality is canceled out by the assigned responsibility, something which it may itself have no concept of.

Spike Jonze, Her, 2013, Film still, Image via zeit.de