What links Jean-Michel Basquiat, alias SAMO©, and Banksy? SCHIRN MAG on the trail of street art in New York and London.

Jean-Michel Basquiat – or rather his oeuvre – is currently on display in London’s Barbican Centre before coming to the SCHIRN in February 2018. His images are hugely influenced by the graffiti aesthetic, which is hardly surprising given that he started out with his Writings in the New York of the 1970s, where graffiti was as much a part of the city as the empty municipal coffers. Nevertheless, Basquiat did not produce complex (text-)images like Lee, Futura2000, Fab5Freddy and other greats of that time. His were plainly design aphorisms.

During the early 1980s graffiti spread from New York City across the world, and now street art (graffiti is a form of street art) is more popular than ever. Book stores stock volumes about street art alongside monographs of Van Gogh and Monet. Similarly, street photography is now afforded the same significance as Brassai and Bresson. We harbor a yearning for what is raw, supposedly authentic – we want street credibility, in contrast to that which is dictated by powerful institutions and media channels. And – something that has not changed since Basquiat’s time – we also want a touch of the mysterious.

Anarchy and rebellion

One of the most popular, fascinating and mysterious street artists of recent years is Banksy. His Pieces and Writings have made headlines not only in London, but all over the world. To this day, it is still not certain who is behind the pseudonym Banksy, and that makes him – anonymously – and his works even more popular. After all, in the age of iPhones, etc., surreptitiously hanging one’s own work in the Tate Gallery, as Banksy did in 2003, has a touch of anarchy and rebellion. But a background in graffiti is not the only thing that links Banksy and Basquiat.

Banksy in the Tate Britain, image via: thetimes.co.uk

In the late 1970s Basquiat teamed up with his friend Al Diaz, and from 1977 they started working under the pseudonym SAMO© (a wordplay on ‘same old shit’), spray-painting aphorisms on the walls of SoHo and the Lower East Side. These were tough times for the city: New York itself was on the brink of ruin and US President Gerald Ford refused to provide state aid to save the city from bankruptcy. The crime rate had doubled.

The spray can as a kind of weapon

Buildings burned nightly in the Bronx, set alight by their owners who were no longer able to let or maintain them. New York was full of graffiti – there was barely a train that was not coated in color. Primarily these were Writings, whereby the text functiones as the central motif of the picture, and often it would be the artist’s own name or pseudonym that was spray-painted as artfully as possible. Many graffiti artists saw the spray can as a kind of weapon. With their Pieces, they were able to draw attention to themselves without standing directly in the limelight as a person. Their images represented them in the public sphere. Artists like Lee then developed their Writings further, away from the narcissistic spraying of their own names, tackling political themes instead.

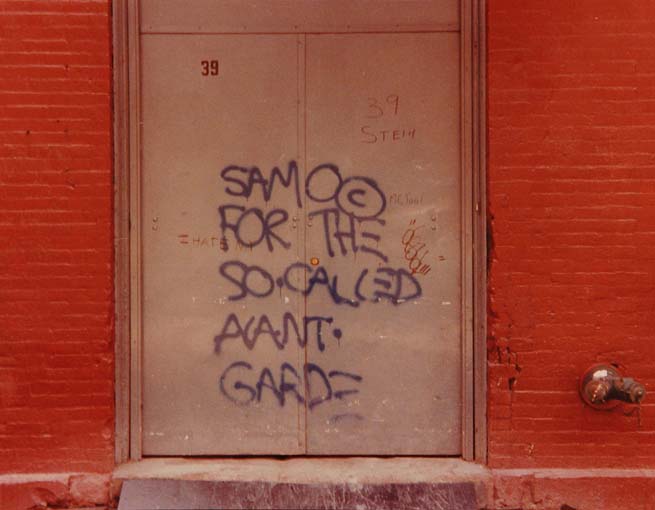

In this chaotic, graffiti-covered city, the aphorisms of Basquiat and Al Diaz appeared reduced and minimalistic, and thus touched a nerve. SAMO© became a sensation. The tone of SAMO© was different, incorporating witty statements: SAMO© AS AN END 2 THE NEON FANTASY CALLED ‘LIFE’ or ANOTHER DAY, ANOTHER TIME, HYPER COOL, ANOTHER WAY 2 KILL SOME TIME. The curiosity surrounding SAMO© eventually become so great that on September 21, 1978, the SoHo Weekly News launched an appeal for the artist to make himself known.

SAMO© is dead

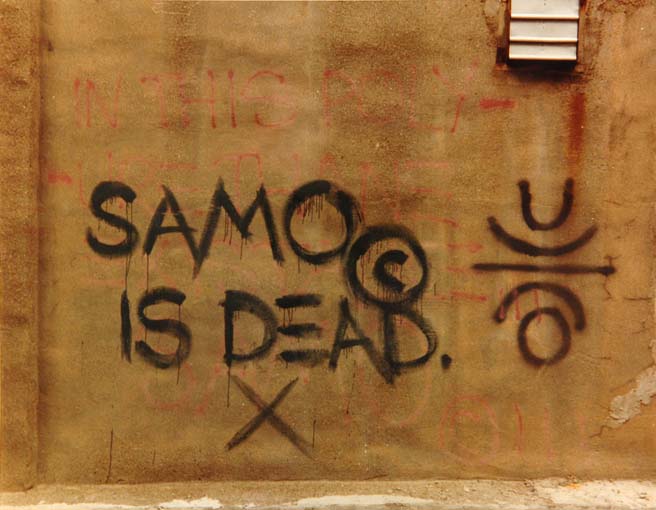

In the newspaper The Village Voice, which resonated far beyond Greenwich Village, the author Philip Faflick wrote about SAMO©, saying that New York had stopped paying any attention to its walls until something new had appeared that fall. This article also revealed the identities of the two artists Jean and Al. The collaboration between Jean and Al fell apart shortly afterwards, Keith Haring gave a eulogy in Club 57, and SAMO© IS DEAD appeared on the walls of SoHo in the aftermath.

Image via: www.henryflynt.org

Image via: henryflynt.org

Undoubtedly it is not only since Basquiat and SAMO© that people have been captivated by the anonymous, the unknown and the mysterious. These days it is particularly fascinating, since it is far from easy to remain anonymous. Nevertheless, Banksy has managed it very well for years; a master of this very art of anonymity. He is the internationally popular street art artist of recent years, and that is undoubtedly not only down to his creativity, but also because his identity has still not been revealed. He became known for his black-and-white Stencils (graffiti spray-painted with the help of a stencil), primarily in London and Bristol. Over the last few years, however, Australia, Germany, the USA and many other countries have also got “their” Banksy.

An (unofficial) collaboration

After a new work of Banksy graffiti appeared in Dover in May (the EU flag, from which a worker is chiseling out a star), Banksy returned to London in September with two works – in time for the opening of the Basquiat exhibition. Both works are painted directly on the external walls of the Barbican Centre itself which, according to Banksy’s Instagram account, has always been careful to remove graffiti immediately.

Image via: www.dazeddigital.com

The first, smaller piece of graffiti shows a Ferris wheel on which the seats or cars are replaced by the crowns that Basquiat so frequently painted. Underneath the wheel people stand in line waiting for a ride – a little sideswipe at the exhibition, perhaps? The second, life-size picture is based on one of Basquiat’s best-known paintings, “Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump”. Banksy has the figure searched by the city’s police and labels the work as a portrait of Basquiat. Perhaps it’s a critical comment on the fact that Basquiat was the first black artist in an art market otherwise dominated by whites and that black people are still far more frequently victims of police discrimination and violence – subjects that Basquiat tackled in many of his works.

The motifs of Banksy’s street art are easy to understand, and the social criticism or criticism of current politics is often bold. This is another element of his popularity, as his works are not cryptic. Banksy is there for all to see, and has something in his creative bag of tricks for everyone. His approach is a stroke of genius, since regardless of whether his works are big or small, he has still never been seen creating them in the public space. Everything immediately finds its way onto YouTube and Facebook, but not Banksy. This leads time and again to speculation that Banksy is not acting alone and perhaps even has an entire workshop. Maintaining anonymity was undoubtedly easier for Jean and Al.

The SAMO© aphorisms have long since disappeared from the walls of New York, but they are not forgotten, since the avant-garde artist Henry Flynt promptly began documenting them. Many of these photographs, which number 57 in total, feature in the exhibition Basquiat. Boom for Real. Although they are considerably younger, most of Banksy’s London works have largely disappeared already too. Transience is the fate of street art. There are still 15 Banksys to be seen, however, and a map shows exactly where. And anyone wanting to experience more of the “Banksy spirit” can now add the “Walled Off Hotel” in Bethlehem to their itinerary.

DIGITORIAL ON THE EXHIBITION

The free Digitorial provides you with background information about the key exhibition aspects.

For desktop, tablet and mobile

Exploring the iceberg

In her works, the artist Grada Kilomba deals with the post-colonial condition, trauma and memory. Schirn Mag spoke to her about aspects of the...

Copy, overwrite, copy again

Anyone who rented a movie after 1976 would have done so on VHS. However, the video tape’s history goes back much further, and is closely connected to...

Downtown 81

Message in a bottle from the 1980s, wandering the streets of New York with Jean-Michel Basquiat. The film Downtown 81 was shot before Basquiat’s big...

Jazz, Bebop and Basquiat

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s record collection is said to have contained some 3,000 LPs. In particular Jazz and Bebop had a huge influence on the artist.

The political force of films

The SCHIRN MAG presents five outstanding films, which do not only deal with racism in the USA, but do also grab its history by the scruff of the neck...

Basquiat's Legacy Today

Accompanying the exhibition “Basquiat. Boom for Real,” a panel discussion will be held at the SCHIRN’s CROWN CLUB on April 12. Taking as their...

Freeform spontaneous

Gonjasufi is on the road a lot: As a singer, DJ, actor and also as a yoga teacher. He will perform at SCHIRN AT NIGHT on April 7. The SCHIRN MAG...

Basquiat in fashion

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s outfits were a permanent composition of opposites. How the young artist became the muse of fashion designers and a role model...

Basquiat and the Beats

Words, signs and symbols. Jean-Michel Basquiat's pieces are truly suffused with fragments of text. One of his most important sources of inspiration...