Anyone who rented a movie after 1976 would have done so on VHS. However, the video tape’s history goes back much further, and is closely connected to the development of television, to video art and to political media guerillas after 1968.

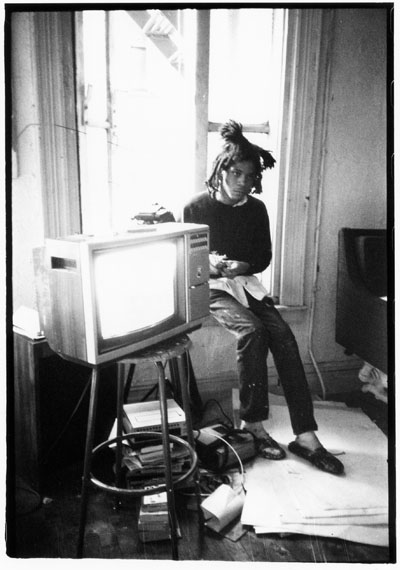

The black plastic cassettes were a favorite of Jean-Michel Basquiat. It’s actually hardly surprising that his studio on Manhattan’s Great Jones Street included a video recorder. He was a member of the “Time Shifts Video” rental store, from which he regularly borrowed movies, and while he painted and sketched at home, the television was always on. His friend from his graffiti days, Fab 5 Freddy, recalls how he often watched films with Basquiat, often on the recommendation of Andy Warhol. These included “L’âge d’or” and “Un chien andalou” by Louis Buñuel, classics of Surrealist film, as if the artist had to quench a thirst for education.

At that time, during the late 1970s and early 1980s, very few people had a video system in their homes. Nevertheless, the term “video” had long been a source of excitement in galleries and soon after also in museums, but its origins lie in the depths of history. Mention of the Latin verb “to see” — “video,” I see — will have to suffice at this point. When exactly the concept of video art emerged from this, nobody can truly say, but certainly Nam June Paik, who was watching films in his studio a decade and a half before Basquiat, played a part here.

A media revolution

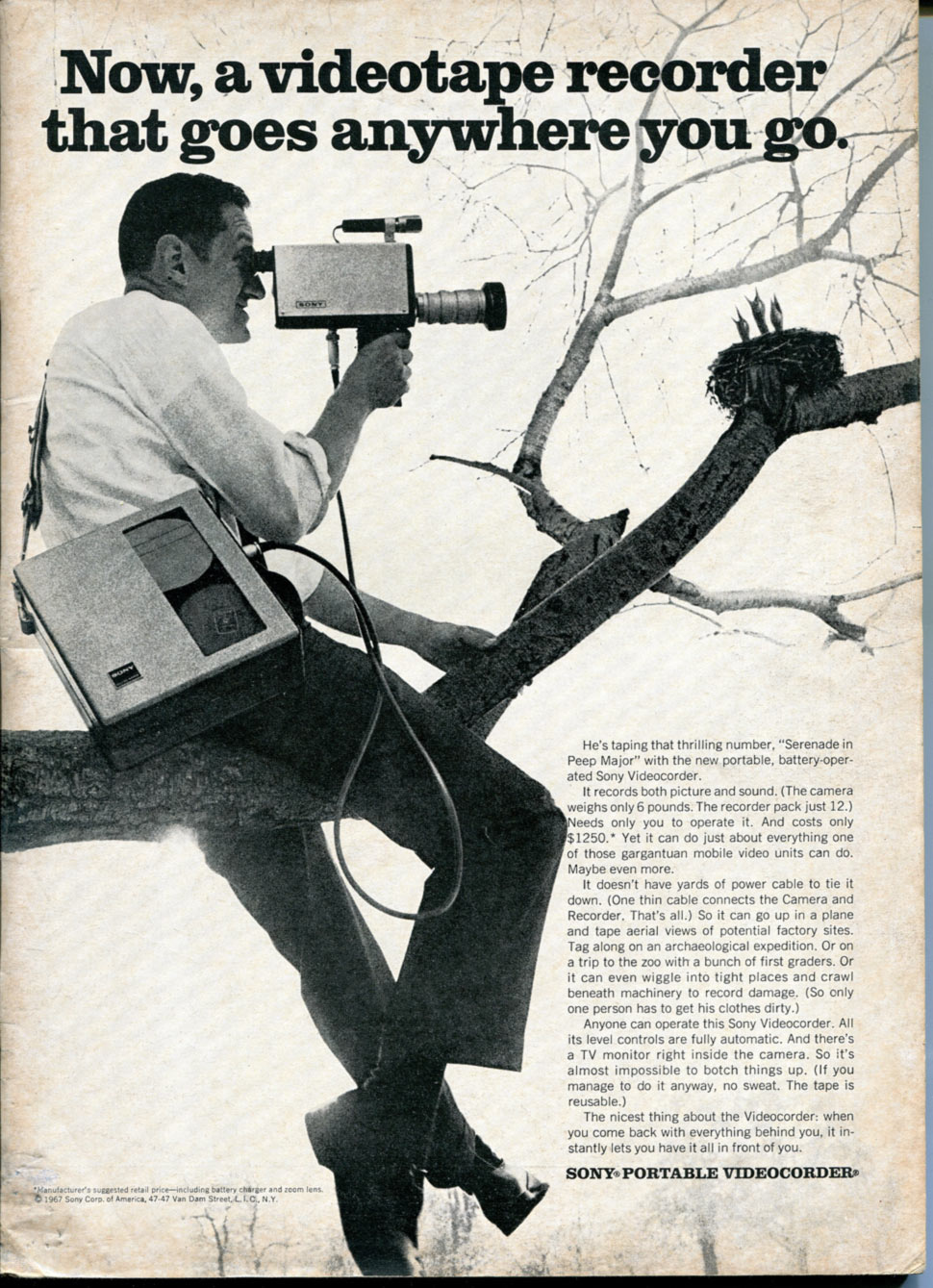

Of course, artists had made films before that: on celluloid, on 8mm or 16mm. But in the mid-1960s something happened that could almost be described as a media revolution. Or, to put it more cautiously, certain developments converged, causing the paths of technology, art and later also politics to cross. Nam June Paik’s friend Noboyuki Idei was a member of the Board at Sony. He gave his artist friend an early version of the Sony Portapak, long before the handheld camera was available on the market. In fall 1964 Paik took the gift with him to New York. There he was one of the first artists to make use of video tapes.

Roland Hagenberg: "Jean-Michel Basquiat, TV", New York, 1983 © Roland Hagenberg, Image via: photography-now.com

Media experts like to highlight that the video tape actually has less in common with film and far more with the audiotape. Indeed, the magnetic image recording did not succeed film, but rather developed virtually parallel to cinema. The first electronic transmission of an image took place in 1911 and thus the idea of television was born. The major difference, however, is that with magnetic recordings the motion is not chopped up into 24 images a second. On a film strip, all images can be seen with the naked eye, but that’s not the case with a video tape.

Storing individual memories

With the Sony Portapak, video became available, and indeed affordable, to the masses. The new technology was hugely promising: Individual memories could be stored, and most importantly, they were worth storing. The images were recorded in real time and replayed in exactly the same way, and it was only this way that television became possible: “The TV image is not a still shot. It is not photo in any sense, but a ceaselessly forming contour of things lined by the scanning finger,” noted media theorist Marshall McLuhan.

Television became the leading medium. The 1960s came to an end and Portapaks were not only the tool of video artists, but also the weapon of choice for activists. In the USA the “alternative media movement” formed within the underground scene, with stations broadcasting on open local channels. There was a magazine called “Radical Software,” published between 1970 and 1974, and DIY manuals with titles like “Guerilla Television.” “Guerrilla Television is grassroots television,” said its author Michael Shamberg. In addition, in his book he explains that guerilla television producers film entirely differently to other broadcasters, namely not from a supposedly neutral standpoint, but rather as participating observers: at protests against the Vietnam War and rallies against the Nixon government.

TV Party: a political cocktail party

“Welcome to TV Party, a TV show that’s a cocktail party, but which could be a political one,” was the catchphrase of Warhol scholar Glenn O’Brien at the end of the 1970s. He had previously been an editor on Warhol’s “Interview Magazine,” then became the presenter of “TV Party,” a show on New York’s public access television, and he carried forward the subversive legacy of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Yet the Lenin portrait in the background could not hide the fact that the political agitation of the 1960s was over. O’Brien was a trickster and he took an anarchic pleasure in confusing viewers as much as possible. For this show, Glenn O’Brien got Debbie Harry, Klaus Nomi, David Byrne and even Jean-Michel Basquiat in front of the camera, and it was here that Basquiat made his first TV appearance.

Basquiat and O'Brien on TV Party, © Glenn O'Brienn, Image via: artnews.com

“It takes many years and a lot of patience before a bonsai really looks like a bonsai,” said Japanese engineer Shizuo Takano, who liked to cultivate the miniature trees in his spare time. It was in 1976 that he and his colleague Yuma Shiraishi presented the VHS cassette. Some claimed that Betamax offered better picture quality, while others pointed out that VHS cassettes offered two hours of recording. In any case, those who could afford it no longer needed to set up a rattling 8-mm projector in their living rooms, let alone the cumbersome screen. This was the final new development in the age of the magnetic tape before it was superseded by digital storage media, and up until the early 2000s the black cassettes were the medium of choice for borrowing, circulating and overwriting movies.

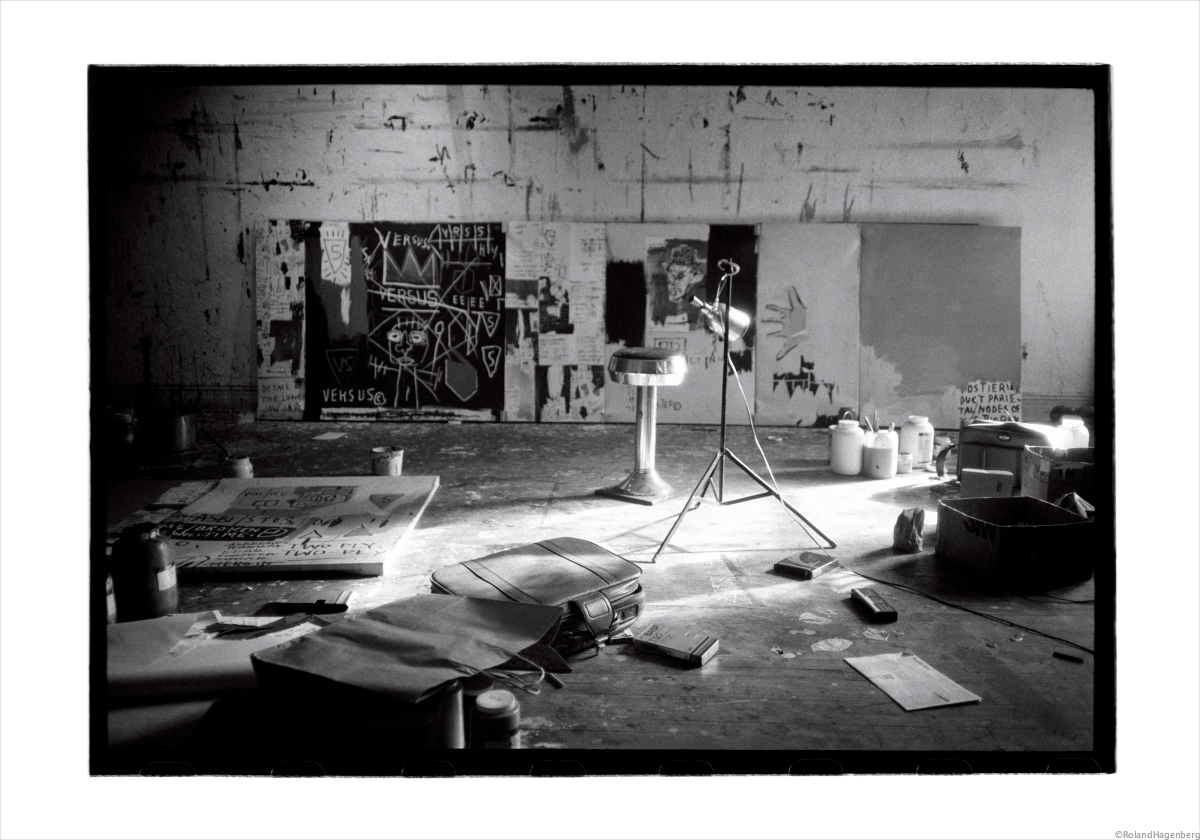

Basquiat's studio on Crosby street, Photo: Roland Hagenberg, Image via: sinsinfineart.com

It’s no surprise that Basquiat was fascinated by video; indeed, in this decade of Punk and post-Punk it represented the most modern of media. It made it possible to enjoy the movie theater at home. Perhaps, however, it’s the logic of the medium itself that fitted so well into the decade of postmodernism: copying, editing, overwriting, copying again.

Exploring the iceberg

In her works, the artist Grada Kilomba deals with the post-colonial condition, trauma and memory. Schirn Mag spoke to her about aspects of the...

Downtown 81

Message in a bottle from the 1980s, wandering the streets of New York with Jean-Michel Basquiat. The film Downtown 81 was shot before Basquiat’s big...

Jazz, Bebop and Basquiat

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s record collection is said to have contained some 3,000 LPs. In particular Jazz and Bebop had a huge influence on the artist.

The political force of films

The SCHIRN MAG presents five outstanding films, which do not only deal with racism in the USA, but do also grab its history by the scruff of the neck...

Basquiat's Legacy Today

Accompanying the exhibition “Basquiat. Boom for Real,” a panel discussion will be held at the SCHIRN’s CROWN CLUB on April 12. Taking as their...

Freeform spontaneous

Gonjasufi is on the road a lot: As a singer, DJ, actor and also as a yoga teacher. He will perform at SCHIRN AT NIGHT on April 7. The SCHIRN MAG...

Basquiat in fashion

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s outfits were a permanent composition of opposites. How the young artist became the muse of fashion designers and a role model...

Basquiat and the Beats

Words, signs and symbols. Jean-Michel Basquiat's pieces are truly suffused with fragments of text. One of his most important sources of inspiration...

Put your high heels on!

Musician and singer Byron Deloatch brings the adventurous spirit of Jean-Michel Basquiat back to life in the CROWN CLUB. In a conversation with SCHIRN...

New York´s New Wave

New York/New Wave: The legendary exhibition at the P.S.1 opened up the New York art scene to the young Jean-Michel Basquiat in 1981. The SCHIRN has...

Basquiat. Boom for Real - Soundtrack

Disco, Punk, Hip-Hop, New Wave and noise: The music scene of New York in the 1970s and 1980s was a source of inspiration for Jean-Michel Basquiat –...

Basquiat’s world: Downtown NYC and the Mudd Club

New York City Downtown: a melting pot of the arts in the late 1970s and early 1980s. It was here that the Mudd Club opened its doors in 1978 – and...

On The Trail Of Basquiat - Part 2

SCHIRN MAG on the road in New York: The second part of the journey into Basquiat’s past takes us from an original SAMO© tag to his longtime studio and...

On the trail of Basquiat

A journey to the past and back to the future: The SCHIRNMAG explores Basquiat’s home turf in New York, from the Green-Wood Cemetery to SoHo, and on to...

#Basquiat

Life-Artist, forerunner of the internet generation, ultimately: a contemporary. Jean-Michel Basquiat’s oeuvre, his life as performance and his...

The fascination of the unknown

What links Jean-Michel Basquiat, alias SAMO©, and Banksy? SCHIRN MAG on the trail of street art in New York and London.

Basquiat. Boom for Real

In February 2018 the SCHIRN will be hosting a large exhibition on the work of US artist Jean-Michel Basquiat.