We take a look at ten particular rainbows in art: For modern and contemporary artists what began many centuries ago as an artistic reflection of a natural phenomenon often has deep personal meaning, which finds expression in new approaches and materials.

Rainbows are created when white light hits a raindrop. So much for the physics. It is the unique form, the translucency, and the sudden appearance and disappearance that have led to the seven-colored band of light giving rise to countless legends and myths in all cultures, arousing fascination among artists since time immemorial. We understand and value rainbows as a connection between Heaven and Earth, between the spiritual and the natural realms, and as a symbol of peace, tolerance, multiculturalism, and inclusion. As a logo and symbol, rainbows are one of the most powerful visual elements of our time.

Ugo Rondinone, life time, 2022

Right now, Ugo Rondinone’s rainbow is already shining above the SCHIRN. It is the first work visitors see when they visit the exhibition, and likewise forms the thematic conclusion of the show. In large, colorful, curved neon letters, the title words LIFE TIME shine above the city: a concise message with which Rondinone aims to reach as many people as possible.

The light sculpture in the form of a rainbow is not only an emblem of respect and inclusion, but also an archaic symbol that has fascinated all the cultures of this earth since time immemorial. life time belongs to Ugo Rondinone’s RAINBOW group of works, in which he deals with inner moods and timeless truths in poetic word combinations and transports them into public space. Homosexuality, freedom and tolerance, day and night are themes that for the Swiss artist are undeniably linked with the symbol of the rainbow. The rainbow shines day after day, night after night, hour after hour. As a simultaneous, powerful reference to Gay Pride, the presence of "life time" is a wonderful sign that is interpreted in a way Rondinone is wholly aware of.

Homosexuality, freedom and tolerance, day and night are themes that for the Swiss artist are inevitably linked to the symbol of the rainbow

Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #1136

“Wall Drawing #1136” is described as “curved and straight colored bands”, and really that says it all: Curved and straight strips of color in all primary and secondary colors, as well as gray, are painted directly onto the wall surface, creating a chromatic environment that envelops the observer. While the first Wall Drawings from the 1960s were monochromatic, LeWitt later introduced colored backgrounds and eventually colorful acrylic paint into his work. This way, he opened up new possibilities and experimented with bright color palettes and bold, graphic forms. “Wall Drawing #1136” unites all the colors of the rainbow – a phenomenon that really fascinated LeWitt in the way it combines nature and the extraordinary. The curve can be read as a continuous rainbow, blurring the boundaries between abstraction and representation.

Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing #1136 © ARS, New York and DACS, London 2021, image via nationalgalleries.org

Judy Chicago, Rainbow AR, 2020

2020: Public life is largely at a standstill. It was during this time that US artist Judy Chicago brought us together virtually. In fact, the physical experience of her works is a key component of her oeuvre, so the app “Rainbow AR” marked a new stage in her longstanding work with pyrotechnics, now supplemented with AR technology. Chicago spent a lot of time developing color systems and the idea that colors can convey emotional states.

In the 1960s, the artist ignited her first “Smoke Sculptures™” in the California desert to “soften the landscape” and to commemorate historically feminine-connoted activities such as fire-making. In her work, Judy Chicago has strived for many years to soften and feminize the harsh, patriarchal world. Using colors and smoke, she achieves this at least as a visual metaphor for positive change, and Rainbow AR now gives everyone the opportunity to experience her work virtually in the space they are in.

Melissa Cody, I am Navajo Barbie, 2016 and Good Luck, 2014

At her loom, Melissa Cody combines traditional patterns with geometric overlays and lively color schemes. The rug works created by the textile artist of the Navajo Nation in northern Arizona, USA, feature Navajo themes like the protective figure Yeei (Rainbow Man) and the Whirling Log symbol of luck, which we know primarily as the swastika. Before its appropriation by the Nazis, the swastika had already been used for thousands of years as a symbol of luck in many parts of the world. In the rug work “I Am Navajo Barbie”, Cody combines the symbols with the title of the work, which is executed in a script reminiscent of 1980s video games: “I am a child of the video game culture of the ’80s: Pac-Man, Frogger, Nintendo”, Cody explains. “I grew up with that world of pixelation.” The symbols described are recurring motifs in her rugs. In “Good Luck”, they are produced in radiant rainbow colors.

Melissa Cody, I am Navajo Barbie, Photo by Scott Cartwright, image via artsandculturetx.com

Sebastião Salgado, Rainbow over the Tucuxim area. Parima Forest Reserve. Yanomami Indigenous Territory, state cloud. State of Acre, 2016

For six years, Sebastião Salgado traveled the Brazilian Amazon and captured the beauty of this unique region in photographs: the rainforest, rivers, mountains, and people. In impressive black-and-white photographs, since the 1970s he has been documenting not only the lives of people on the margins of society, but also the landscapes of our planet that are worth preserving yet are often threatened. His photographs often bear witness to great drama, as shown in this shot of a double rainbow amidst the imposing cloudscape.

Sebastião Salgado, Rainbow over the Tucuxim area. Parima Forest Reserve. Yanomami Indigenous Territory, state cloud. State of Acre, 2016, image via taschen.com

Olafur Eliasson, Your Rainbow Panorama, 2006-2011

There’s one thing not to be missed on a trip to Aarhus, Denmark: a visit to Olafur Eliasson’s installation “Your Rainbow Panorama,” which has been on the roof of ARoS since 2011. No less a work than Dante’s “Divine Comedy” is said to have served as the model for the museum building, which is crowned by paradise in the form of the rainbow. On slender columns above the roof, the panoramic walkway extends from one end of the cube-shaped building’s facade to the other.

The installation offers a panoramic view of Aarhus and the surrounding landscape – in all the colors of the rainbow. The lighter colors lay a soft focus over the city, while the darker colors highlight the contrasts. Eliasson himself says of the work, “I have created a space that you could almost say erases the boundary between inside and outside – a place where you are uncertain whether you have entered a work of art or a part of the museum. This uncertainty is important to me because it stimulates people to think and feel beyond the boundaries within which they are used to functioning.”

Olafur Eliasson, Your Rainbow Panorama, 2006-2011, image via olafureliasson.net

Olafur Eliasson, Your Rainbow Panorama, 2006-2011, image via olafureliasson.net

rainbow series #4

Candice Breitz, Rainbow Series, 1996, image via kaufmannrepetto.com

Candice Breitz, Rainbow Series, 1996

White South African artist Candice Breitz presented her “Rainbow Series” two years after the end of Apartheid and the first democratic elections in South Africa. With the controversial collages of abstract female figures, which she reassembled from fragments of (porn) magazines and postcards, she examined racist and gender stereotypes and commented in an ironic albeit controversial vein on the “rainbow nation” of South Africa. This term was coined by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela and refers, among other things, to the new, supposedly peaceful unity of multiculturalism in a country that until recently was characterized by strict racial segregation. The artist is one of the critics of the “rainbowism” ideology, which Breitz describes as utopian because it glosses over real domestic problems, such as the legacy of racism, under the guise of rainbow peace. The collages are uncomfortable and hard to tolerate – but they challenge visual conventions by critically examining common assumptions.

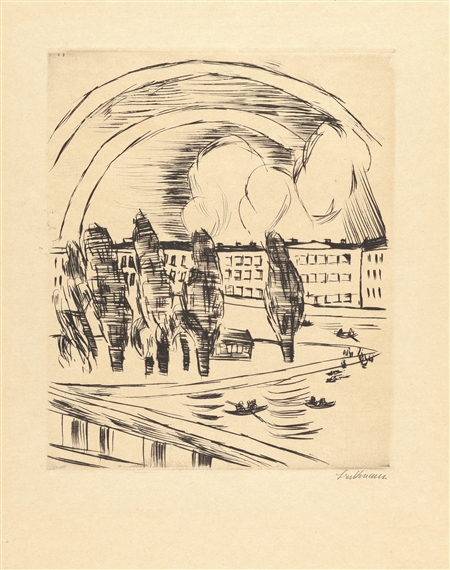

Max Beckmann, Mainlandschaft mit Regenbogen (River Main Landscape with Rainbow), 1923

More than any other artist, Max Beckmann is associated with the city of Frankfurt. Traumatized by his experiences as a medical assistant during World War I, Beckmann came to the Main metropolis in 1915 and created a large proportion of his key works here, among them self-portraits, portraits, and numerous views of Frankfurt. These also included the etching “Mainlandschaft mit Regenbogen”, which presumably shows the Main Island and the northern bank from the perspective of Sachsenhausen. Beckmann lived and worked there for 17 years not far from the Städelschule (then the School of Arts and Crafts), where he taught a master class from 1925 to 1933. When the Nazis seized power, he lost his position and went first to Berlin, emigrating subsequently to Amsterdam in 1937 and to the USA in 1948.

Max Beckmann, Mainlandschaft mit Regenbogen,1923, image via mutualart.com

Zakariya ibn Muhammad Qazwini, Illustration of a Rainbow, The Wonders of Creation, 13. Jh

In the 13th century, the Persian scholar Zakariyya’ al-Qazwini (Abu Yahya Zakariya’ ibn Muhammad al-Qazwini) created the two-part illustrated cosmography “The Wonders of Creation and Unique [Phenomena] of Existence”. For centuries, the work was one of the most widely read books in the Islamic world, and it was frequently copied and translated. The mere title indicates that the author did not write a scientific work, but rather wanted to show the amazing diversity of (divine) creation. In the first of two “Maqalas” (speeches), Qazwini writes about planets, constellations, and angels. In the second part, he describes the earthly and goes into detail about the four elements, the seas, living beings, plants, and weather phenomena. These also include rainbows, which here stand for the many ways God works.

The rainbow stands here for the many ways in which God works

Caspar David Friedrich, Gebirgslandschaft mit Regenbogen, 1809

Enigmatic, romantic, religious – and to this day not unequivocally deciphered: This aptly describes the rainbow in Caspar David Friedrich’s “Mountain Landscape with Rainbow”. One is quickly inclined to dismiss the work as a typical painting for the artist, but something prompts a pause: Why does a rainbow cross the presumably nocturnal scene? Are we dealing with the rare phenomenon of the lunar rainbow or is it a religious symbol? Scholars often interpret the rainbow as a personal religious confession or as a sign of peace between God and man from the Old Testament story of Noah. In any case, one thing is clear: There is probably no scientific evidence for this rainbow. But maybe there are things between heaven and earth that can barely be explained...

Caspar David Friedrich, Gebirgslandschaft mit Regenbogen, 1809, image via artsandculture.google.com