One title, two works: With her photo series “The Americans” Gauri Gill references the 1950s photo book of the same name by Swiss photographer Robert Frank. A comparison shows that Robert Frank’s distanced gaze has given way in Gauri Gill’s images to an insight into the private realm.

Gauri Gill spent almost eight years working on her photo series “The Americans”. In the 1990s, while still a student at the Parsons School for Design in New York, she produced the first images, expanding on them in subsequent years in the course of several trips to various different states in the US, such as New Jersey, Tennessee, and California. The long periods of time Gill often requires in order to create a cycle of works gives an indication of how she proceeds as a photographer and an artist: In constant interaction with the persons she photographs she establishes a personal and in part close friendly relationship to them, often accompanying their lives for several years, in this way capturing the passage of time such as can be deduced from their faces, relationships, the familiar setting, or the political landscape. She always does so while maintaining a documentary distance that buttresses the authenticity of the different series.

The Southeast Asian diaspora in the USA

This productive synergy of interpersonal relationships and documentary eye behind the camera also forms the basis for the series “The Americans”. Gill photographed the Southeast Asian diaspora living in the United States and to this end visited relatives and friends in their homes or at work, in downtown New York and in the suburbs, accompanying them during their leisure-time pursuits, and recorded intimate moments of their family and private lives. The result are color images from the everyday life of the Southeast Asian community that Gill then assembles in diptychs or displays on their own. They show people clad in saris or wearing dastars, eating or phoning, at weddings, in clubs, or performing holy Hindu rituals. In “The Americans”, the personal lives of the Southeast Asian diaspora come up against the general idea of Americans and American culture. This juxtaposition would initially suggest that “The Americans” be read as a commentary on US integration policies – debates on membership of society, identity, and postcolonial narratives doubtless play an important part in understanding Gill’s oeuvre.

A comparison with the eponymous series of images by Swiss photographer Robert Frank that was first published in 1958 as a photobook and to which Gill alludes with the title for her own series makes it abundantly clear that her project goes far beyond sociographic documentation.

Frank produced his series in the course of two years on a travel stipend from the Guggenheim Museum. His black-and-white photographs present workers at conveyor belts, Hollywood stars, empty diners, Orthodox Jews during Yom Kippur or a Black family driving by in their car. In American post-War society, “The Americans” provoked sharp criticism, on the one hand because of its portrayal of violence, racial segregation, poverty, and consumer culture and, on the other, because at the time Frank was judged to be very amateurish in the photographic techniques he used.

free of any staging

What both series have in common is the documentary style of the photographs that when viewed give rise to the impression that the moments and occurrences were shot seemingly by chance free of any staging. Frank took this method of depiction so far that presumably some of the people portrayed neither realized they were being photographed nor gave their permission, like the young couple who looked back at him startled, if not annoyed when he stood behind them pressing the shutter release. Moreover, Gill resorts to some of the themes from Frank’s 1958 series or creates formal aesthetic parallels to them, for example when capturing groups of young people in bars or clubs, or by relying on recurrent themes such as cars, the Stars and Stripes flag, or flickering TV screens and ad billboards.

Robert Frank, The Americans, San Francisco 1956, Image via fotomagazin.de

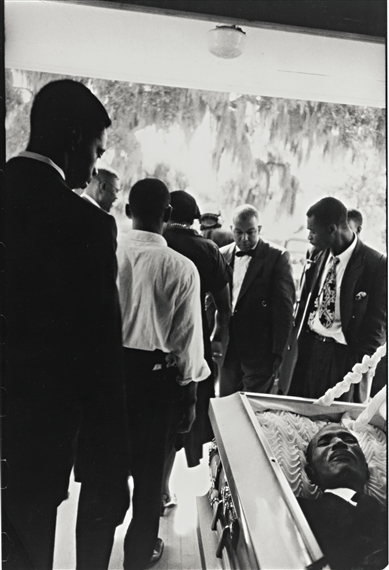

Among the most impressive moments in Gill’s series is the image of the funeral of Prem Kumar Walekar, shot dead in 2002 at a gas station by the D.C. sniper attacks. Gill juxtaposes the image of the open coffin to a portrait of the son of the deceased, whose hands are clenched into fists and who stares into the camera with a rigid gaze. Frank’s series also includes a similar image of a funeral with an open coffin as well as a group of mourners who have gathered outdoors. This theme shows how Gill’s stance toward her work differs from that taken by Frank. Both use the camera to document this greatest emotional moment of bidding farewell and of sorrow and portray the emotions that can be grasped with empathy across all generations, groups of the population, and religious communities.

Focusing on the interpersonal

However, Gill creates an interpersonal level between herself and the subject matter, first by presenting the two scenes as a diptych and secondly by depicting the young man’s gaze into the camera; this can presumably be attributed to Gill relating personally to what she portrays, something that also affects the viewer. While as an observer Frank preserves a distance to what he records and, on that basis, then documents the pluralism and contradictions of American society, such as it revealed itself to him as an outsider commentator in 1958, Gill in the 2000s takes a glimpse into the private worlds of the Southeast Asian community, shows them in their homes, at family festivals and at religious ceremonies.

Robert Frank, Funeral - St. Helena, South Carolina, 1955, Image via mutualart.com

Gauri Gill, Taxi driver Prem Kumar Walekar, 54, was shot dead at a gas station in Rockville, Montgomery by a sniper. Seen at right is his son at the funeral. Maryland 2002, Image via lassiwithlavina.com

She offers us insights into the private worlds of the people portrayed and in this regard her oeuvre is decidedly unlike that of Frank’s series. In combination with her documentary style, in Gill’s “The Americans” we can see with empathy a universal image of community, tradition, home, and lived experience that goes beyond all cultural specificities and can be grasped and read over and above the diasporan identity of the community she portrays.

Gauri Gill. Acts of Resistance and Repair

13. October 13, 2022 - January 8, 2023