Like Bruno Gironcoli’s monumental sculptures, Rube Goldberg’s crazy constructions examine the human element of the machine. And give instructions for nose wiping and catching mice.

Don’t you find it frustrating, too, when you’re eating and you don’t have any hands free to wipe your nose? And isn’t it always impossible to fish an olive out from deep down in a long-necked bottle? If you wanted to praise Rube Goldberg in one of today’s ubiquitous service texts, you would probably write something like this – offering the solution for the very specific problems immediately.

Reuben Garrett Lucius Goldberg, born in 1883 in San Francisco, was very successful as a cartoonist during his lifetime. Thousands of his comic strips were published, and later in life he created animated stories for television. Goldberg was a “Rock star” in his day, says Renny Pritikin, co-curator of the exhibition “The Art Of Rube Goldberg”, which was held in 2018 at the Jewish Museum of San Francisco.

The Rube Goldberg machine stands for the nonsensical inventions of his cartoons

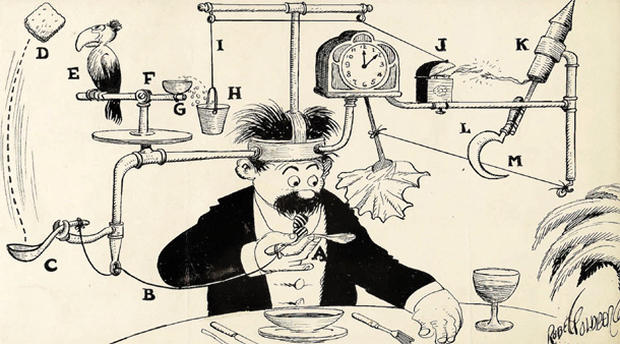

Originally an engineering student, he came to world fame for his mad inventions, which are best described as “complicated contraptions” or “goofy gizmos”, although they now bear a name of their own: Rube Goldberg machines. Goldberg’s machines existed primarily as an idea. Drawn in his comics and strongly characterized by the wit of the early 20th century, you could find nonsensical but useful inventions like the “self-operating napkins”, for example. Later in his career, Rube Goldberg also worked as a game developer, with his best-known work and probably the template for the now popular classic “Mouse Trap” (which itself is a kind of Rube Goldberg machine).

Rube Goldberg, Boob McNutt, Image via blogspot.com

Rube Goldberg, Self Operating Napkin © Heirs of Rube Goldberg/Courtesy Abrams Books, Image via cbsistatic.com

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3629700/76_suicide_copy.0.png)

Rube Goldberg, Suicide Machine © Heirs of Rube Goldberg, Image via cdn.com

His constructions have long since made it into popular culture via other channels too, and thus have become part of the real world: In 1987, Purdue University in Indiana launched the first “National Rube Goldberg Machine Competition”, and various other teaching and research institutions followed suit. Three hundred individual steps for blowing up a balloon or turning on the lights of a Christmas tree: The lengthier and more complex the route to the final goal the better.

Simple objects ignite a fire in an accomplished chain reaction

For their 2010 video clip to “This Too Shall Pass”, Chicago-based band “OK Go” presented a specially constructed Rube Goldberg machine made of more than 700 household objects, which set various actions in motion over the course of a good four minutes, eventually leading to an explosive paint gun ending. In the area of fine art, Swiss artist duo Fischli and Weiss made use of a similar principle with “Der Lauf der Dinge” (“The Way Things Go”) in 1987. With the difference that for them the process is not the means to an end as such, as is the case in the actual Rube Goldberg machine, but rather the purpose itself lies in the interaction of the means (although one could also ultimately see this as quintessential to all the above-mentioned contraptions).

Rube Goldberg, Mouse Trap Game, Image via blogspot.com

The artist duo declared that their work tackled the great questions of moral theory, guilt and innocence, which in this chain of reactions appeared to be indivisibly connected dialectically. In their outsized experiments, simple everyday objects form a chain reaction verging on the grotesque, which ultimately sparks a flame, puts it out again and allows smoke to rise, but sets in motion all manner of great things as it does so. The work became a favorite among visitors to documenta 8. Which takes us back to Rube Goldberg, who didn’t actually build any machines himself, but rather sketched plans for possible constructions, to which he said: The most important thing is to make the observer laugh.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the machines people liked were no doubt those whose efficiency did not trigger shock and fear. Crucially, in some of their characteristics Rube Goldberg’s constructions are inferior to human beings – hence they act in a hopelessly more laborious, lengthy manner to achieve something that humans would be able to do very capably without technical assistance (indeed, in the USA the name “Rube Goldberg” is now synonymous with actions carried out in a particularly laborious way).

Despite this, Goldberg’s drawings at times revealed more glaringly than elsewhere the disquieting notion that the machine made by human hand doesn’t necessarily have to be human-friendly. Goldberg’s humor could often verge on dark, as in the “Automatic Suicide Device for Unlucky Stock Speculators” from 1914. The age-old question of who’s the cynic here – the human designer or the executing machine is – appears to have been answered by Rube Goldberg at least, and unequivocally so.

Rube Goldberg, Peace Today © Heirs of Rube Goldberg/Courtesy Abrams Books, Image via pinimg.com