Seeing sounds and tasting colors: Synesthesia remains a mysterious neurological phenomenon that has provided inspiration for artists time and again.

How do human beings actually perceive colors, sounds, letters and periods of time? As you might expect, it’s not that easy to answer this question. Synesthetes at least have one thing in common in this regard: Their world is very colorful.

Anyone who is “affected” by synesthesia – which is not an illness or a disorder but rather, according to neuropsychology, a “normal variant of perception” – will see colors and patterns, for example, in their mind’s eye when they hear music; they will taste or smell names, assign a quality or a color to letters, and connect weekdays with a geometric form.

Around four percent of people exhibit one of the at least 73 different forms of synesthesia, which can also be inherited. Synesthesia is not like a stimulated pattern of reactions – the sensory impressions occur at the same time and cannot be separated from one another. “A subjective sensation or image of a sense (as of color) other than the one (as of sound) being stimulated” is an official definition of synesthesia. The patterns and colors that emerge from this are perceived on an “inner screen” around the level of the forehead and do not change over time: Anyone who perceives the sound of a trumpet as a yellow circle will do so throughout their life.

Kandinsky’s paintings are the outcome of him hearing colors

It’s a subject of fascination that has long insipired writers, musicians and fine artists. Study of this innate connection of different senses reached its first high point in the 19th century, both with regard to fact-based science and artistic romanticism. “Synesthesia” is also being used to describe a linguistic stylistic device from which we get expressions like “loud colors.” One hundred years later, there is a renewed interest in synesthesia: Conferences are being held at the interface between science and art, and psychologists and neurologists attempt to take a look inside the minds of synesthetes.

Artists, meanwhile, have never stopped working in interdisciplinary and multisensory ways and referring to synesthesia in doing so. Some of the most famous examples are undoubtedly the pictorial compositions by Bauhaus artist Wassily Kandinsky, who was probably gifted with the ability to “hear colors” himself. His abstract forms and patterns are similar to the experiences of many synesthetes when they come into contact with music. Joan Mitchell too, who exhibited several variations of synesthesia, took inspiration from music for her abstract expressionist paintings. While Kandinsky and Mitchell brought the images from their minds to the canvas, Giselher Klebe did the opposite: In 1949-50 the composer created an orchestral work as a response to the watercolor „Zwitscher-Maschine“ (Twittering Machine) by Paul Klee (1922).

What color is hell?

As technology developed, the possibilities for making synesthetic experiences perceptible to non-synesthetes increased. In an exhibition in Wuppertal in 1963, Nam June Paik, a member of the Fluxus movement and a pioneer of video art, presented “Kuba TV,” a work made up of two televisions that brought together image and sound in a new correlation: On one of them, sounds were translated via a microphone into rapidly changing patterns on the screen, while a tape recorder was attached to the other – the sounds generated were visible but not audible to the observer.

Joan Mitchell, Chicago, 1966–67 © Estate of Joan Mitchell, Image via www.joanmitchellfoundation.org

Paul Klee, Zwitscher-Maschine, 1922, Image via wikimedia.org

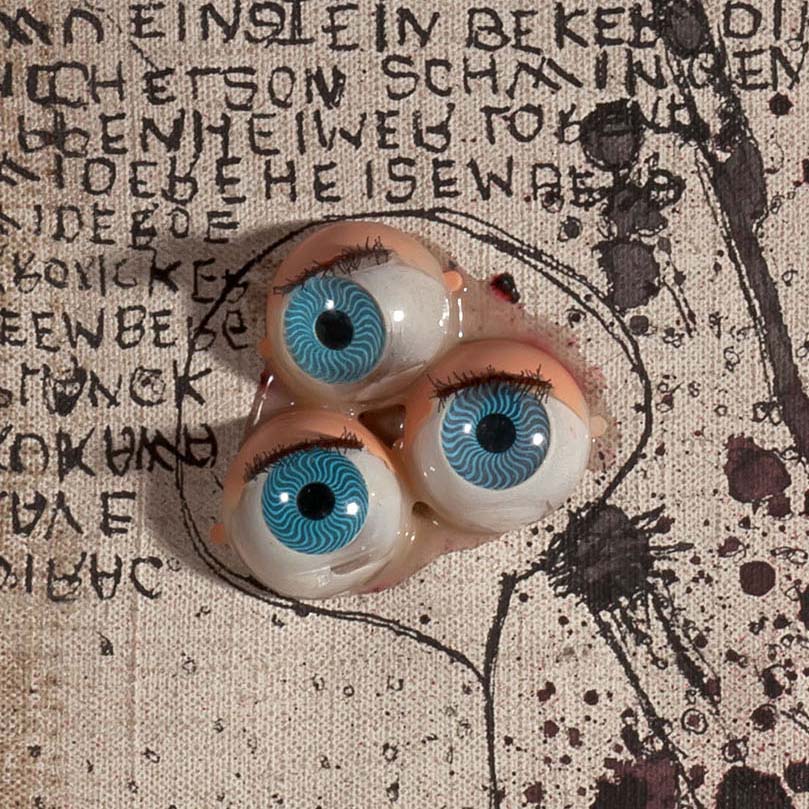

Even fifty years later, the moving image still seems to be the favored means by which the neurological phenomenon is investigated and creatively processed. In the ten-year research project “Why is Green a Red Word?,” Danish artist Ditte Lyngkær Pedersen asked multiple synesthetes to tell her about their perception. Her video “What the Hell Does Purgatory Look Like?” shows a white surface on which the English word “Purgatory” is written in black letters.

In a voiceover she reads out descriptions of terms from people who exhibit grapheme-color synesthesia, for whom letters and numbers are inextricably linked with a color. The complexity of the perception of letter sequences – multilayered color gradients, framing and resulting associations – is on the whole often hard to put into words. Something similar emerges in the work “A Study of a Name,” in which the artist asked synesthetes to verbalize their perceptions as reactions to their first name.

Since, in principle, more senses are at work in synesthetes, it is suspected that they are better able to develop creative approaches than other people – and to orient themselves, for example, differently within their surroundings. With her work “That Can’t be September – It Smells Like the August of 1985!,” artist Barbara Ryan gives expression to this.

That can’t be September – it smells like the August of 1985!

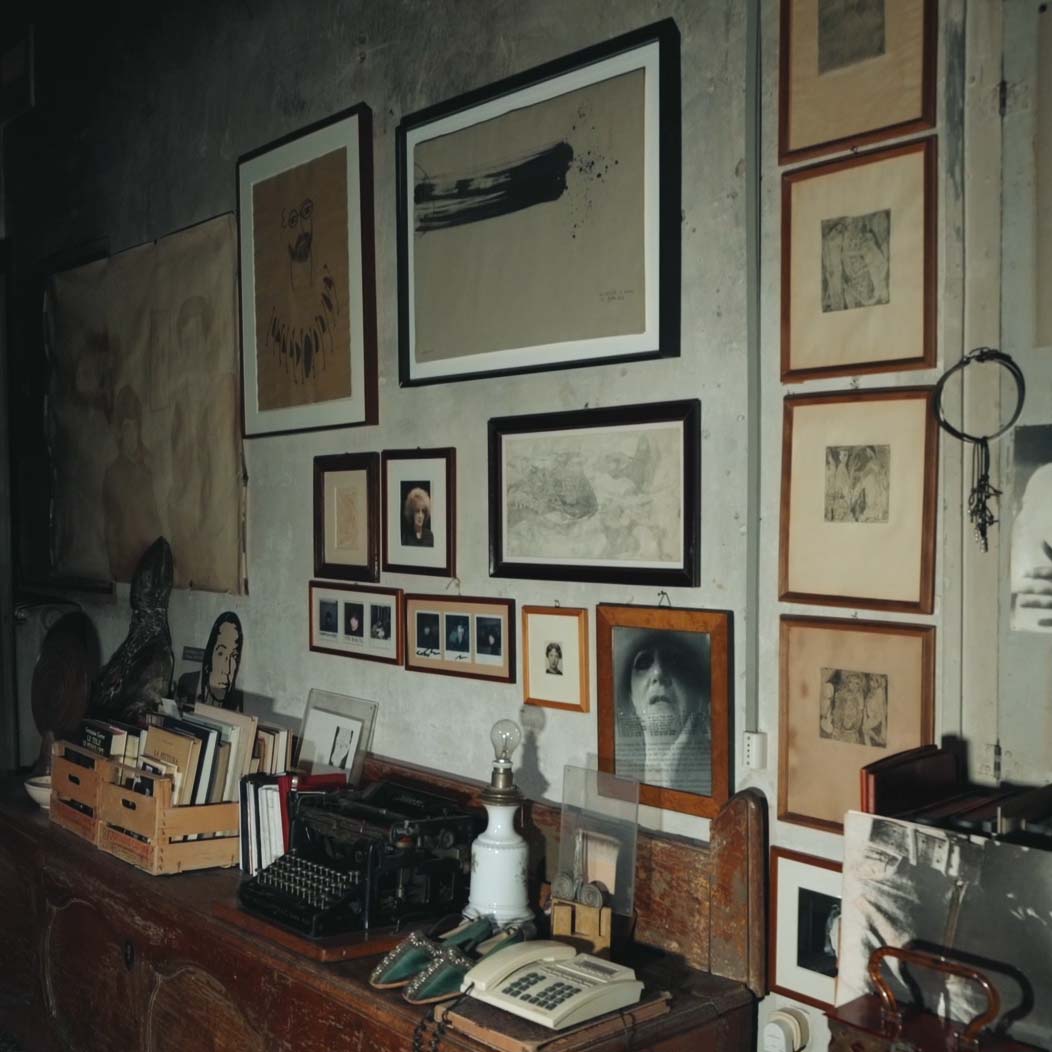

Barbara Ryan, That can’t be September – it smells like the August of 1985!, Installationsansicht, 2012, Image via www.artlaboratory-berlin.org

During her time in Berlin in the 1990s she mapped out an extensive installation in which observers could perceive the city through her eyes by means of photos, but also with descriptions of smells, colors and sensations. A similarly participatory approach can be seen in “A Banquet for Ultra Bankruptcy,” which was realized by artist duo Carl Rowe and Simon Davenport in 2013 at the Berlin project space Art Laboratory. Up to six guests took part in a shared dinner of six courses at which the food was supplemented with images, sounds and smells and thus made into a multisensory experience.

Making synesthetes’ impressions perceptible to outsiders remains a complex task

Artists have been exploring the various forms of sensory perception for centuries. Yet despite progress in research and in digital representation, making synesthetes’ audiovisual or haptic impressions perceptible to outsiders remains both a complex and inspiring task – and it’s a problem that will probably only be solved once we have the technological means to see the world through another person’s eyes.

Carl Rowe & Simon Davenport, A Banquet for Ultra Bankruptcy, 2013, Foto © Tim Deussen, Image via blogspot.com

Carl Rowe & Simon Davenport, A Banquet for Ultra Bankruptcy, 2013, Foto © Tim Deussen, Image via blogspot.com